Photographs and text by Norbert Schiller

My first contact with the “Tanker War” was in July 1987, when I was on assignment for Agence France Presse (AFP) to photograph the navy frigate USS Stark as it transited the Suez Canal on its way to home to Mayport Florida after suffering some serious damage as it patrolled the Persian Gulf. As the conflict developed and the United States became a major player, my involvement in covering the war also progressed leading me to the frontlines of a major international crisis.

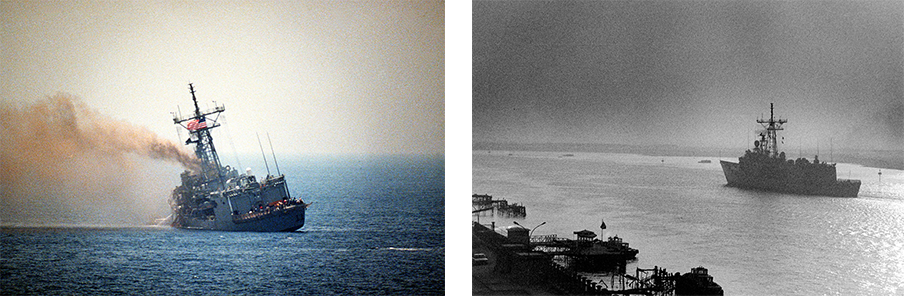

The reason for the interest in the USS Stark was that two months before it sailed through the canal, it was attacked by an Iraqi Mirage fighter jet which fired two Exocet missiles into the warship’s hull crippling it and killing 37 of its crew. The Iraqi pilot responsible for the shooting later claimed that he had mistaken the U.S. frigate for an Iranian warship.

The U.S. frigate USS Stark burns after it was mistakenly hit by two Exocet missiles fired from an Iraqi fighter jet. Two month later a repaired USS Stark transits the Suez Canal en route to the U.S. Phot. (L) USN

The attack had strong reverberations in Washington where Ronald Reagan’s administration came under intense pressure to define the role of the U.S. navy in the Persian Gulf, especially now that one of its ships had been attacked. Although the Reagan administration accepted Iraq’s apology and even went a step further by blaming Iran for escalating the conflict, it was clear that the U.S. would no longer remain officially neutral, as it had been since this regional conflict erupted in 1980.

A navy helicopter leads a convoy of reflagged oil tankers.

The threat of higher oil prices, coupled with an increased Soviet presence in the Gulf, prompted Washington to use the USS Stark incident as an excuse to increase its involvement in the region. Consequently, the U.S. announced its intentions to reflag 11 Kuwaiti oil tankers and man the ships with American crews. On July 24, 1987 operation Earnest Will began when the first ship convoy left Kuwait under the protection of the U.S. Navy. This move made the United States the sole guardian of Kuwait’s fleet of oil tankers while sailing through the troubled waters of the Gulf.

Background to the Iran Iraq War:

The Iran-Iraq War officially began following a series of skirmishes over control of the 200-kilometer Shatt al-Arab waterway that bordered both countries. On September 22, 1980 Saddam Hussein launched an all-out surprise attack crossing Shatt al Arab and capturing the oil-rich southern Iranian province of Khuzestan and the strategic city of Khorramshahr. The Iraqi leader believed that he would be able to pull this off while Iran was still in a state of chaos following the 1978-79 Islamic Revolution. Hussein purposely attacked Khuzestan, where the majority of the population was ethnically Arab, thinking that its residents would be more sympathetic to his cause. In the early stages of the invasion, Iraqi forces had little difficulty advancing against an unprepared Iranian military. However, it didn’t take long for Iran to regroup and mount a counter offensive. To the surprise of many, mainly Saddam Hussein, the Iranians managed to recapture most of the land lost and advance well into Iraqi territory.

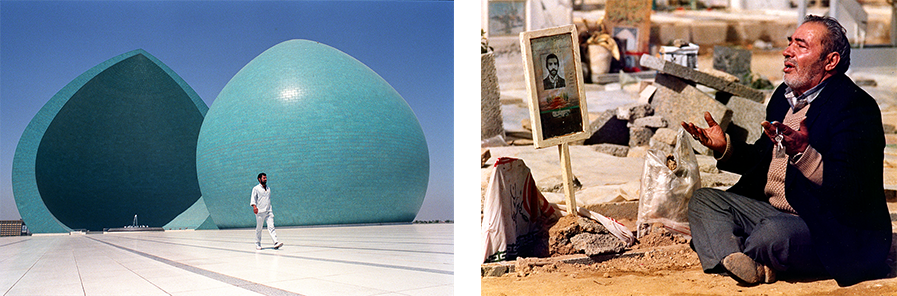

Al Shaheed monument erected in Baghdad to commemorate the Iraqi soldiers who died in the war with Iran. An Iranian father at Behesht-e Zahra cemetery in southern Tehran weeps at the gravesite of his son who was killed in the war with Iraq

By 1984, the land war was at a stalemate with little or no gains for either side. In an effort to break the impasse, both countries turned the conflict up a notch and began attacking each other’s economic interests. In the beginning, the attacks were limited to seaports and oil facilities, but they soon began targeting shipping, particularly oil tankers that sailed to and from loading terminals in the Gulf. This new phase became known as the “Tanker War” and by the time it ended four years later, over 400 ships, mostly oil tankers, had been sunk or damaged and hundreds of sailors had been killed or injured.

An oil tanker burns out of control after it was attacked by Iranian Revolutionary Guards riding in Boghammar speedboats armed with rocket-propelled grenades.

It was no secret that the rich Gulf Arab countries, were helping fund Iraq’s war machines. Since Iran could not disrupt all Iraqi oil exports, particularly the oil that was sent overland by pipeline and tanker truck to Turkey and Jordan, the Iranians went after Iraq’s two key allies, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. This meant that all oil tankers entering the Gulf destined to either of those two countries were potential targets. After the U.S. agreed to reflag 11 Kuwaiti super tankers, the Iranian navy began attacking all maritime ships going to Arab ports regardless of the cargo.

Covering the Tanker War:

Prior to America’s entry into the conflict press coverage of the war was minimal at best. However, after the USS Stark incident and ship reflagging, the Tanker War story jumped from obscurity to the front pages. Overnight, the press corps converged on Dubai, Bahrain, and Kuwait, the only countries willing to let journalist report freely, although there were restrictions. Journalists could not mention the host countries by name and television correspondents were not allowed to stand in front of any recognizable landmarks, so doing standups in front of palm trees became the norm. Another sensitive issue was making references the “Persian Gulf,” which Arab states insisted on calling the “Arabian Gulf” in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War.

A television cameraman films while standing on the skids of a helicopter. Television news crews converged on Dubai after it was announced that the US navy would begin escorting Kuwaiti oil tankers through the Gulf.

A few months after Reagan made the decision to reflag the tankers, I was sent to Dubai to cover the conflict for what I thought was going to be a one-month rotation to relieve one of my colleagues. Little did I know that my one month would last until the war ended the following August.

My colleague warned me that the major challenge in covering this conflict was logistical, due to the high cost of chartering a helicopter. To keep the cost down, he made the rounds every morning to the different hotels that housed the major American television networks offering a fee in exchange for a ride on their helicopter. For the major networks it was not so much a matter of money, but space availability. In cases where the correspondent decided not to fly at the last minute, there would be a seat available. And even if we were lucky enough to get a ride, it didn’t mean that there would be anything interesting to photograph.

On my first few days, I chartered a small plane because it was much cheaper than a helicopter, and I could cover greater distances. However, it was far more difficult to take photographs from a plane that at best could circle the area I wanted to shoot. Also, it was difficult to take pictures from a tiny opening in the glass window. A helicopter, on the other hand, could hover over an area for a long time and the doors could be easily removed to accommodate more than one person shooting pictures or video. However, since I had just arrived, my main concern was to get my name on the wire so the editors could see that I was working.

I used a 300mm 2.8 lens for most of the photos I took from the helicopter. However, when the US navy told us to stay three miles away from their convoys, I either added a 1.4 teleconverter or doubler to extend the lens’ focal length. Phot. (R) Greg English

My biggest problem was not having anyone to tip me off when a U.S. flagged convoy was passing or when the Iranians attacked a ship. At the time, AFP had very little representation in the Gulf, so the task of finding out information was largely my responsibility. I therefore decided to take a gamble and sit in one of the television newsrooms to wait for something to happen and pray that there would be an empty seat on the chopper for me.

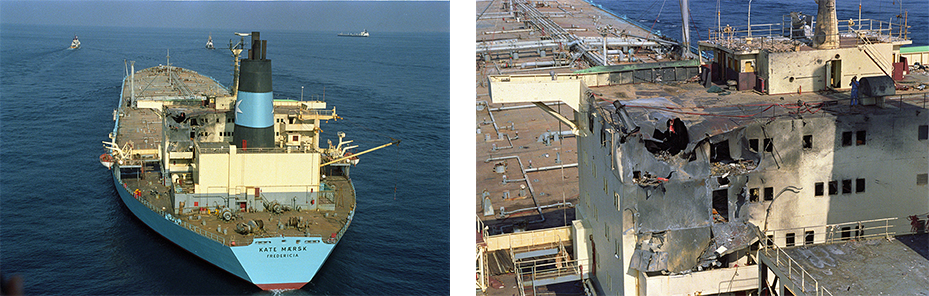

The 339-thousand ton Danish flagged oil tanker Kate Marsk is towed out of the Gulf by three tugboats after its bridge was struck by an Iranian missile. One crew member died and three others were seriously injured in the attack.

We removed all the doors from our helicopter so we us could work unimpeded. Phot. Fredrick Neema

After making the rounds with the TV networks, I found that the only one that was interested in cooperating with me on a regular basis was the new kid on the block, Cable News Network (CNN). The CNN crew was staying in the same hotel as me, and they were on a very tight budget. Back then, CNN was a far cry from the multibillion-dollar network it is today. It operated on a modest budget and was contemptuously called the “chicken noodle network” by journalists who worked for the more established and wealthier networks such as ABC, CBS and NBC. Because of their financial restrictions, CNN crews were always looking to share helicopter costs with press photographers. The first taker was the Associated Press photographer, followed by me. This relationship was made official in a contract between the three agencies and Abu Dhabi Aviation, the helicopter company that we hired. After I secured the helicopter deal, AFP decided to keep me in Dubai indefinitely, which suited me just fine.

We shared the smallest helicopter in the fleet, a Bell 206, and in order to accommodate everyone, we removed all the doors allowing us to shoot in all directions. In the beginning, the coverage was somewhat chaotic. The first time we arrived at the scene of a stricken ship burning at sea, the three of us began yelling out simultaneous instructions to our pilot who was trying to meet our demands while navigating his way around other news helicopters at the scene. After the initial pandemonium, the three of us cameramen and pilot got into a more harmonious rhythm.

Black smoke bellows out from the stern of the Norwegian-flagged oil tanker Happy Kari after it was attacked by an Iranian warship

A typical day would start with us gathering at the makeshift CNN office to see what had happened overnight, and if there were any announced naval escorts. Besides the Americans, there were 13 other navies in the Gulf escorting ships from their respective nations. Normally, the US military would announce the departure of one of its convoys which gave us an idea of its approximate arrival time in the waters near Dubai. Once we were up in the air, the CNN correspondent, who remained on the ground, would monitor channel 16 (emergency frequency channel) on the Marine VHF radio for attacks. When an attack on a ship occurred, the correspondent would radio us and suddenly it would be a race to see which news crew could get to the burning ship first. The race was also played out on the water between service tugboats eager for a big payday in the event they would have to rescue crew or extinguish a fire. Many service companies would station tugboats in the shipping lanes to improve their chances. I use to think of us in the press helicopters as vultures and the tugboats as sharks. On clear days it was easy to see smoke rising from a ship in distress. However, during the hazy days of spring and summer, we would almost be on top of the blaze before spotting it. The biggest problem with photographing U.S. escorted convoys was that once we identified ourselves as a news chopper, the military would warn us to stay at a distance of at least three nautical miles. That meant we had to use very long lenses and shoot at a fast shutter speed to avoid having blurred pictures. I used a 300/2.8 lens and added a teleconverter in order to double it to 600mm. Once the U.S. navy got to know a particular news crew they occasionally allowed them to get closer, which made for far better photographs and video footage.

A USS Chandler helicopter helps rescue crew from the Cypriot-flagged oil tanker Pivot after it was attacked and set ablaze by rocket- propelled grenades fired from Iranian Boghammar speedboats

It was extremely rare to capture an Iranian warship in an attack. The Iranians were usually long gone by the time we arrived to the scene. Moreover, Iran rarely used its warships in these operation, opting for the fast moving Swedish-made Boghammar speedboats armed with rocket propelled grenades and small arms. The Boghammars were so fast that they were able to hit their targets and get out of harm’s way before any of the navies patrolling the Gulf managed to send a support ship or helicopter to intervene.

An Iranian warship overtakes the Romanian-flagged oil tanker Dacia after attacking the ship and setting it ablaze. Crew on board the Dacia use water hoses to extinguish the flames.

A Boghammar manned by Revolutionary Guards. The speedboat was the most effective weapon the Iranians had to attack ships due to its ability to quickly attack and get out of harm’s way before one of the navies patrolling the Gulf could mount a counter-attack.

In spite of all this, we were the only news crew to witness an attack involving an Iranian warship. It happened just off the coast of Sharjah in United Arab Emirates, as we were flying overhead. An Iranian warship came up from behind a cargo ship opened fire, and then sped away. It happened so fast that our pilot had to swiftly swerve the chopper to enable us to capture both the warship and the burning cargo ship in the same frame. We then flew in close and photographed the crew desperately trying to put out the blaze. Our other encounter happened when we descended closer to the water to investigate what appeared to be some fishing boats. However, when we got close enough, we realized that those were two Boghammar speedboats which opened fire as soon as they spotted us. After adroitly pulling us out of harm’s way our pilot, an experienced Vietnam War pilot, downplayed the incident saying, “that’s nothing; try and land a chopper in a ‘hot’ DMZ (Demilitarized Zone) in ‘Nam’ when the enemy is shooting at you from all directions!”

Some news choppers occasionally became involved in rescuing crews from burning ships. However, since our helicopter was the smallest in the fleet and every seat was taken, it was nearly impossible for us to be of any assistance. On one occasion though we arrived to a stricken ship that was in flames and it seemed like all the crew had already been rescued. After circling the ship and taking pictures, we were about to leave when we saw the ship lean to one side. Suddenly, a man appeared on the bridge frantically waving his arms. Since the ship looked like it was sinking, our pilot skillfully lowered the chopper so that the man, who happened to be the captain, could climb onboard.

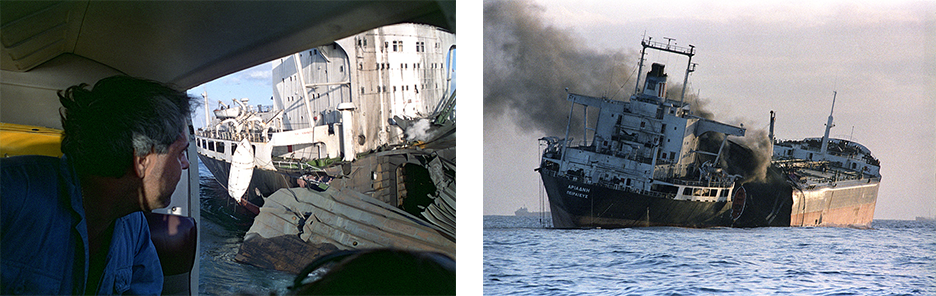

The captain of the Adriande looks at his ship after being rescued by our news helicopter. The Adriande was attacked twice on the same day; first by Revolutionary Guards on Boghammar speedboats using rocket-propelled grenades and then by a missile from an Iranian warship.

After being hit by a water canon, our helicopter makes an emergency landing on the back of a tugboat. The Adriande can be seen burning in the distance.

Unfortunately this rescue operation did not have a happy ending. After getting permission to land on the back of a rescue tugboat to drop off the captain, a crew member manning a fire hose turned the water canon on us as we approached forcing the pilot to abort the landing. Shortly after being airborne, we heard a loud noise coming from the engine followed by a loss of power. Suddenly, it was us who were in trouble and had to request to make an emergency landing on the back of the same tugboat that turned the firehose on us.

After a safe landing and as we were tying down the chopper to the rescue tug, the man who had caused the crash came up to our pilot and asked whether he could get a “certificate for shooting down the first helicopter in the Tanker War.”

Although the Tanker War has been dwarfed by more horrific conflicts that have occurred in the Middle East over the past three decades, it still plays a significant role in the lives of those who have experienced it. In October 2017, Florentin Dacian Botta, a former merchant marine from Romania, contacted me out of the blue to say that he had read a story I wrote on the 25th anniversary of the conflict. Dacian had been aboard the Romanian registered Fundulea, when it was intercepted by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards on November 23, 1987 as it entered the Persian Gulf through the Straits of Hormuz. After questioning the captain about the ship’s destination and cargo, the Iranians opened fire on the vessel. Two crew were seriously injured in the attack and the ships captain died later in hospital. Shortly after the attack, we arrived at the scene in our helicopter and photographed the aftermath.

On November 23, 2017 the crew of the Romanian-flagged ship Fundulea gathered at the Seamen’s Club in Constanta to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Iranian attack on their ship. Florentin Dacian Botta (second from left bottom row) was the former crew member who contacted me for photographs to show at the event.

This past November, the Fundulea crew met at the Seamen’s Club in Constanta, Romania, to mark the 30th anniversary of the attack and celebrate their survival. On Dacian’s request, I supplied the photographs that helped them relive this intense and unforgettable experience.

I was your pilot on B206 A6-BCF, 15th. Dec 1987. I run across your link while searching for something else. I was happy to see your photos and it took a minute to recognize my self on the back of the Clamore. Your description of what happened was very well written and accurate. Hope this finds you well,and wishing you all the best in the future.

My dad was aboard the vessel Happy Kari, which was attacked in 1988. The tanker was attacked twice. First in dec. 1987 and then in 1988. On the first voyage after docking.

My dad was the chief engineer. In an interview with a Norwegian broadcaster following the attack, was as follows:

Reporter: What did you think and feel when you saw the huge flames incapsulating the ship? What kind of thoughts ran through your head? ( hoping for a vibrant story, I guess)

Dad: We need to put it out. The fire.

End of story. My dad was a man of few words. 😊 May seem like a cool fella, my mom knew the whole story. Nights in soaking wet sheets…

I arrived in Dubai on September 11th 1987 to fly a Bell 212 for CBS News. The Tanker war caused worldwide consternation and was the leading subject of the evening news. We monitored most radio contacts offshore and air traffic as well. Wherever some confrontation occurred we tried to find the location and our cameraman would direct me to the most appropriate position. On September 13 we followed the US Navy helicopter carrier USS Guadalcanal and we noticed a transport ship that was following the Carrier. Our crew identified the ship as a German Navy vessel which seemed strange since the German Navy did not have any ships in the Gulf that we were aware of. I approached to within a half mile and our Producer decided it was safe enough to close in. As I approached from astern I could not make out any name on the ship but the Iranian flag was flying. Gilles, our Producer, was delighted and told me to hold next to the ship. Both cannons on the ship were pointing at us but the crew was waving in a friendly manner. We stayed with the ship for a few minutes, their crews were taking photos of us and Roberto, our cameraman, scanned the ship from bow to stern. I slowly moved off to the north and was contacted by the Guadalcanal radio operator not to approach them within five miles or they would open fire. I told them we were flying a UAE commercial helicopter with an American CBS news team. They acknowledged but demanded we stay outside their five mile safety limit. We did. However, the incident was somewhat exciting.

On September 23rd we followed two Belgian Mine sweepers off Fujairah. The Belgian Navy was attempting the clear mines that were floating within the commercial water ways of tankers. A UAE speed boat approached and demanded that we move off. We ignored the demand and kept filming the Belgians. The crew kept waving at us and took photos of our filming. Suddenly we noticed the UAE speedboat below us. We hovered about 150 feet above the ocean when a flair was fired at us from below which actually went through our rotor disc. I immediately flew off and was contacted by the speedboat radio operator who demanded that we land at the Fujairah airport and wait for the police to deal with us. We assumed that they were after the news reel and the team prepared another reel with Dubai soul footage to hand over. That was done and we flew back to Dubai. The Dubai Police paid CBS a visit and demanded the proper tape. Which they received. The crew had copied the original but decided not to publish the flair incident since CBS would most likely had been banned from further TV work. It was an exciting time and I enjoyed flying with such a professional crew. Roberto Moreno , camera man, and Viviana his wife was the sound person, were absolute great to work with. Bert Quint was my favorite reporter. What a nice man and great orator!

Your website is missing a critical part of the tanker wars. US Navy Specwar boat units were present during the entire Operation Earnest Will and Prime Chance. Both East and West Coast squadrons played critical roles escorting the US Minesweepers during their day time operations against Iranian speed boat attacks. They also participated in the convoys, whereas the US Frigates dropped in behind the deep draft tankers due to the persistent mine threats, our Patrol Boats were weaving to and fro the convoy route.