By Zina Hemady

Photographs by Norbert Schiller

Northern Ethiopia is the part of the country that until the 20th century constituted what had historically been recognized as Ethiopia. It is associated with the country’s ancient civilizations dating back to pre-Christian times. The ancient Egyptians traded with these parts which they referred to as the land of Punt, while the ancient Greeks used the term Ethiopic or “burnt faced” to describe the people who lived there. With the introduction of Christianity in the 4th century A.D., the Orthodox Christian empires of the highlands became synonymous with Ethiopia to the European superpowers of the time. The first leg of our trip consisted of a visit to Lake Tana and the Blue Nile to admire medieval monasteries and one of Africa’s legendary water falls, and to Gondar where every year thousands converge to celebrate Timket, or Epiphany.

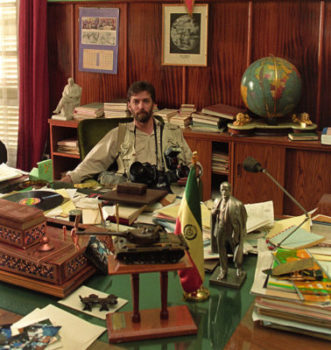

Norbert sitting at the desk of communist leader Mengistu Haile Mariam a few days after he was deposed in June 1991

The trip, organized by Liban Trek a Lebanese hiking group that also offers cultural programs, had a hectic itinerary designed to maximize our visit. From the beginning, there were signs that our adventure would be fraught with unexpected surprises which anyone who has lived in or traveled extensively to the developing world would have learned to expect. However, Ethiopia, which until 1991 was under the brutal military rule of communist leader Mengistu Haile Mariam, is even behind other impoverished nations turned tourism magnets, and has much catching up to do in terms of infrastructure and general knowhow required to meet the rising numbers of yearly visitors. The first upset was an error by the local travel agent who booked us on an internal flight before we had even landed in the capital, Addis Ababa. That is when we learned about “Ethiopian time,” one of the country’s idiosyncrasies which is the cause of many snafus. In addition to following a 13-month calendar, Ethiopia operates on a 12 hour clock, as opposed to 24 hours anywhere else, and asking anyone for the time requires a mind boggling calculation. As the unfortunate victims of this cultural mixup, we had to spend our first vacation day at the Addis airport, after taking the redeye from Beirut, as our resourceful guide Hailom pleaded with the many “bosses” at Ethiopian Airlines to find seats for us on the next plane. After torturous hours of waiting we finally arrived in Bahir Dar at the end of the day. We had some catching up to do, but we were determined not to let this mishap put a damper on the trip.

Two small boats waiting to ferry passengers across the Blue Nile just above the Blue Nile Falls.

The highlights in the capital of the Amhara region, home to the most prominent but no longer largest of Ethiopia’s 70 ethnicities, were Lake Tana, a vast inland sea where the Blue Nile originates, the Blue Nile Falls further south, and the monasteries and churches on the lake. The guidebooks warn travelers about being disappointed by the falls, especially when visiting during the dry season, due to the water’s diversion to feed a hydroelectric dam. However, the visit more than made up for the previous day’s frustrations as we watched the powerful torrent fall off the black rocks while refreshing us with its mist. On the way back to Bahir Dar we stopped at an open air market in the village of Tis Abay or Smoke of the Nile Falls, which looked like it had been transported from the Middle Ages as locals in tattered clothes bought and sold an unlikely assortment of goods including spices, second hand plastic shoes, colored reeds for basket weaving, and even dried cow carcasses which would later serve as ground covers in their huts.

A man carrying a cow carcass at the Tis Abay open market. Sellers use umbrellas to protect themselves from the midday sun.

After a hurried lunch on a motor boat we headed to the monastery of Debre Maryam or Saint Mary, one of the prominent 20 or so monasteries that were built on Lake Tana’s islands and peninsulas as of the 14th century when the area became a political power center and spiritual sanctuary. The church, like many in Ethiopia, is circular in shape and is believed to date back to the 14th century, but has been rebuilt many times over the centuries, most recently in 1970. The internal walls, which date from the 19th century and form the holiest section of the church, are covered from top to bottom with religious motifs which we would see repeated in most houses of prayer that we visited. The art focuses on themes including the life of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and Ethiopian saints whose torture is often graphically depicted in the frescos.

Biblical scenes of torture from the new testament are painted inside the 19th century Saint Mary’s church located on a small island on lake Tana

Poverty is prevalent in Ethiopia. Women dry hot peppers by the side of the road to use for the popular berbere paste.

The next destination, Gondar, was advertised on our schedule as the apogee of the trip as it is the site of the most elaborate Timket or Epiphany celebration in Ethiopia drawing thousands, or maybe even tens of thousands, of local and international visitors every year. The drive from Bahir Dar to Gondar is along a 175 km (109 mile) agricultural road where the vast majority of dwellings consist of huts built with the thin trunks of Eucalyptus trees covered with cow dung and grasses and a grass roof. As a longtime Cairo resident, I had lived face-to-face with poverty, yet I was unprepared for the wretchedness that I witnessed in Ethiopia. Centuries of autocratic rule starting with the first century Axumite kings down to the 237th monarch of the Solomonic Dynasty Haile Selassi, who was replaced by an equally ruthless military junta, have brought the population to its knees.

Perhaps the best example of the Machiavellian scheming that characterized Ethiopia’s royal houses is the history of the Gondarine line established by King Fasiladas. When the invading Moslem armies of Ahmed Gragn posed a serious threat to Fasiladas’s father Susenyos, the king struck an uncomfortable alliance with the Portuguese who sent troops to rescue his faltering empire. However, Portuguese aid came with a hefty price tag which was the imposition of Catholicism on a population deeply committed to its Coptic Orthodox faith. Susenyos’s conversion to Catholicism was hugely unpopular and led to his dethroning in 1632 by his son who threw out the Portuguese and restored the Orthodox Church. Fasiladas moved the capital to Gondar where he built a fairytale-like palace which was later expanded by his successors into a complex of six castles and smaller buildings.

The Castle of Emperor Fasiladas, built around 1640. The 33m high palace with its domed towers is the most impressive in this palatial complex. The roof of Iyasu the Great’s palace was destroyed by British bombardment in World War II.

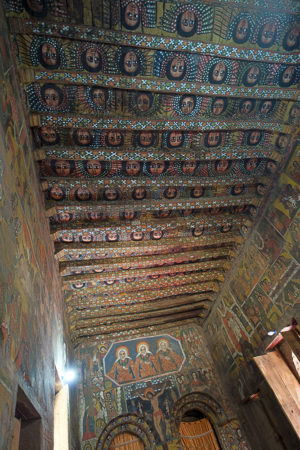

Cherubic faces on the ceiling of Debre Berhan Selassie church.

As the city was gearing up for the Timket festivities, we visited the 17th century stone-walled Fasil Ghebi palatial compound, a UNESCO World Heritage site. More fascinating than the architecture, a blend of Portuguese, Axumite, and Indian styles, is the turbulent history and that characterized the Gondarine era where poison was commonly used by power hungry court members to kill their rulers and ascend to the throne. Therefore, the Gondar royals, commonly referred to as the Camelot Dynasty, hired bodyguards whose main duty was to sample their food. Some of the buildings, including the once sumptuously decorated castle of Iyasu the Great were destroyed by British bombardment of Italian forces stationed at Fasil Ghebi during World War II.

The next site was the Debre Berhan Selassie church, which translates as “The Mountain of Light.” Many legends surround this sumptuous church including the one that attributes its survival of the Moslem raids of 1888 to a swarm of angry bees that kept the attackers at bay. The original circular church was destroyed by lightning and rebuilt in the 18th century apparently in the rectangular shape of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. In addition to its magnificent architecture, the church features some of the country’s most impressive paintings including the 80 cherubic faces on the ceiling that have come to be associated with Ethiopian church art and the frightful image of the devil engulfed in flames.

Early afternoon, we headed to the Piazza, the Italian town center, to watch the Timket procession. The parade, well worth the anticipation, included participants from the 40 or so churches located in the area. The main attraction was the priests dressed in luxurious gowns carrying replicas of the Tabot or Ark of the Covenant on their heads as they walked on a red carpet covered in blades of grass which was being rolled out and then rolled back up by a group of young men who scurried ahead. Also noticeable were the floats created for the ceremony including one featuring a water pourer. The procession, heading to Fasiladas’s Pool about 2 km (1.3 miles) away where prayers would be held at dawn, was accompanied by a sea of worshippers — men, women, and children all dressed in white. This captivating visual feast was complimented by the sound of chanting and ululation, and the smell of incense wafting from urns carried by the priests.

Thousands of worshippers accompanied by priests carrying replicas of the Ark of the Covenant on their heads (L) parade through the streets during Epiphany celebrations.

After a bishop blesses the water hundreds of worshippers jump into Fasiladas’ s Pool to commemorate the baptism of Jesus.

What was less enchanting however, was the en masse baptism at Fasiladas’s Pool for which we had to wake up at 3:30 a.m in order to reserve our spots on the makeshift bleachers overlooking the water. We sat crammed like sardines for four hours in the bone chilling cold as more tourists squeezed their way to the stands to watch worshippers disrobe and and hurl themselves into the freezing pool after it had been blessed by the bishop. Although the finale was impressive, it was not worth the agonizing wait. Some relief came in the afternoon with our visit to the Debre Sina Maryam in Gorgora, 65 km (40 miles) south of Gondar on the northern shore of Lake Tana. The monastery’s isolated and natural setting is more conducive to spirituality than the frenzy of the Timket celebrations. The present church, built by Fasiladas at the site of an earlier version, features some of the oldest and most authentic murals in the Lake Tana region although they are in desperate need of restoration. Some of the art is believed to date back to Fasiladas’s reign and to have been commissioned by his sister Melako Tawit.