Text and photographs by Norbert Schiller

Egypt’s President Mubarak (L) and Tunisian President Ben Ali seen fraternizing together 20 years before the Arab Spring would remove both leaders from power.

The “Arab Spring” turned the tide against a number of Arab leaders who for decades had been synonymous with the countries they controlled with an iron fist. Those autocrats, including Tunisia’s Zine El Abedine Ben Ali, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh and Syria’s Bashar al Assad, who is still fighting a protracted civil war, shared similar histories and ruling styles, which led their people to revolt against them. Of all these despots, Libya’s Colonel Muammar Gaddafi occupied a category of his own due to his quixotic and capricious nature which tried the patience of his countrymen as well as his fellow Arab leaders. His most infamous displays of extravaganza were well documented in the media, but one less publicized incident includes a private tour of the Egyptian museum at night.

It’s been nearly seven years since Gaddafi was deposed and subsequently executed in cold blood after he was found hiding in a drainage pipe near his hometown of Sirte. His death marked the end of era, during which the Colonel reigned supreme for 42 years. During that time, the international community often marginalized Libya for crimes allegedly committed by its ruler.

Gaddafi and Mubarak meeting inside a tent in the middle of the desert outside the Egyptian border town of El Saloum in 1992

For the press corps, Gaddafi was more than just another Arab leader; he was a constant and reliable source of entertainment. During the 25 years that I worked as a photographer in the Middle East and North Africa, the Libyan leader’s antics were commonly received as a welcome distraction from otherwise mundane assignments. An ordinary meeting with Mubarak to discuss bilateral relations turned theatrical when Gaddafi decided to hold the talks in a tent in the middle of the desert. Never mind that it was a total of 16 hours round trip from Cairo to El Salloum where the meeting was held. During his visits to Cairo, he would often have his tent set up on the presidential palace grounds and have camels brought into the compound to provide him with fresh milk every morning.

Gaddafi listening to an aid at the 2003 Arab Summit in Sharm el Sheikh

When Gaddafi’s convoy reached Sharm el Sheikh, it caused a gridlock in the resort town where the roads were not equipped to handle such congestion. While the Egyptian authorities had made it clear to all the delegations that only the vehicle transporting the head of state to the venue would be allowed to drive up to the entrance, Gaddafi’s twelve-car convoy naturally not comply. As soon as the leader’s white limo passed through the security gate, the Egyptian guards quickly threw down barricades to stop the rest of the vehicles from going through. However, the car carrying Gaddafi’s infamous female bodyguards had managed to squeeze in. Suddenly there was mayhem as security tried to hold back a group of armed Amazonia women who were bent on accompanying their leader to the conference.

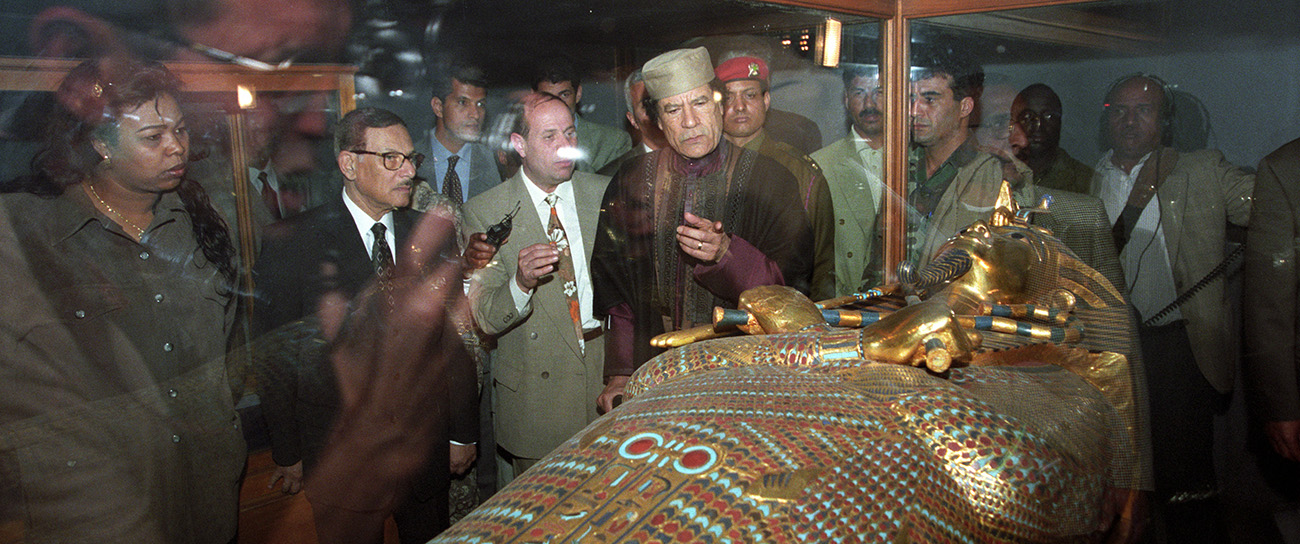

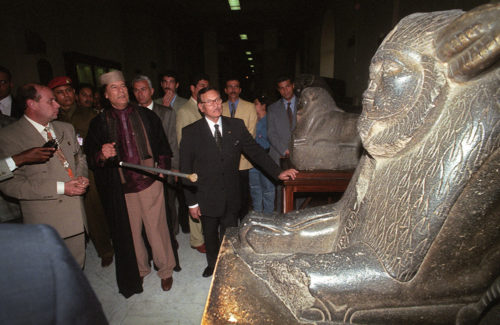

Gaddafi with his museum guide (L) and a very perturbed Egyptian Minister of Information, Safwat el Sherif (R) in 1999

Still, I decided to drive by the museum entrance to see for myself if there were any preparations for a high profile visit. When I arrived, the lights were off and the gate was locked, indicating that the museum was closed for the night. However, I noticed some colleagues lingering around outside the gate with cameras in hand. After waiting for a while, we all decided to give it another 15 minutes. Just as we were about to call it quits, we heard a wail of sirens in the distance and, like magic, the museum doors flung open, the lights came on, and security guards appeared out of nowhere.

To everyone’s surprise Gaddafi was accompanied by a very small entourage, which included his chief of protocol Nuri al Nismari, his favorite female bodyguard “Fatima,” and a few others in his security detail. Waiting outside the museum to greet Gaddafi, was Egyptian Minister of Information Safwat Sherif, who looked unamused about the whimsical leader’s late night tour. It was obvious that he also had been given very short notice about the visit and given no option.

Gaddafi’s tour of the museum abruptly ended after he visited King Tutankhamun’s chamber.

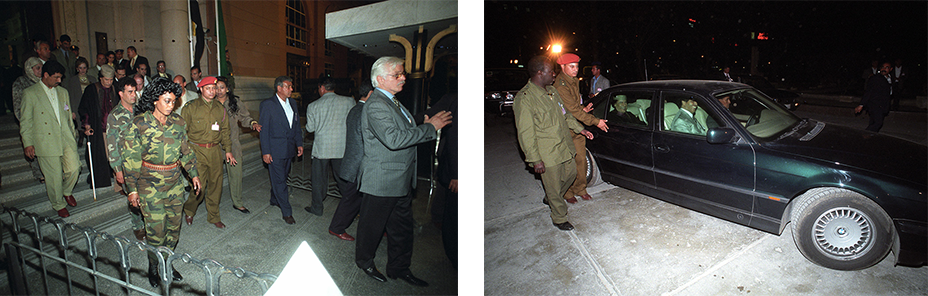

The tour started with the normal jostling as photographers scrambled to get a good shot, but once the photo op was over, everyone left to file their pictures. Since the printing deadline for most newspapers had passed, I decided to stick around to see if anything interesting would transpire. The guide took Gaddafi on a standard tour stopping at a number of designated relics to give his rehearsed script. However, the Libyan leader was keen on more elaborate explanations, which delighted the guide who was more than eager to oblige. Unfortunately, Sherif was not thrilled and did everything in his power to cut short the visit. When Gaddafi asked to go down a dark corridor, Sherif quickly claimed that this section of the museum had no power. Instead, the minister took Gaddafi to the King Tut exhibition, the museum’s most coveted display of pharaonic treasures, and then quickly ushered him out of the building. We had barely made it outside when the doors were slammed shut and the lights turned off. Gaddafi and his entourage sped off into the night.

Gaddafi leaving the Egyptian Museum with his entourage that included Chief of Protocol Nuri al Mismari (left photo far right)) and his chief female bodyguard “Fatima.”

Over the years I photographed numerous heads of states from the Americas, Asia, and Europe standing at the Sphinx or climbing down into some tomb, but I never had the opportunity to take pictures of Arab leaders at similar locations as they rarely ventured of the guest residences where they were lodged. Therefore, Gaddafi’s late night at the museum can be added to the factors that have contributed to his legacy as the wacky dictator who stood out from the crowd.