Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

I recently watched the latest Tom Cruise film, “Top Gun: Maverik.” Like its iconic 35-year-old predecessor, “Top Gun,” the movie was action-packed, with a plethora of high and low flying daredevil maneuvers. Those scenes may have invoked various reactions among the audience, but to me they triggered decades-old memories of the times I spent on aircraft carriers as a photojournalist. To keep the spirit of the original film, Tom Cruise insisted on including the 1986 soundtrack “Danger Zone” in the sequel, as a new reminder of the dangers fighter pilots face when they fly off the carrier on a mission.

An F-18 taking off from the flight deck of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower.

My first experience photographing warships dates back to 1986 when I boarded a French minesweeper Vinh Long taking part in an underwater archeological expedition. The Vinh Long was involved in a campaign to locate one of Napoleon’s ships, Le Patriote, which hit a reef and sank off the coast of Alexandria in 1798. The ship had already been found when I boarded the minesweeper, but I watched the underwater archeological team hoist up numerous canons and boxes filled with dynamite from the wreckage.

The French minesweeper Vinh Long (L) located the whereabouts of Napoleon’s ship Le Patriote that sunk off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt in 1798. A service tugboat lifts a canon out of the water from the stricken ship.

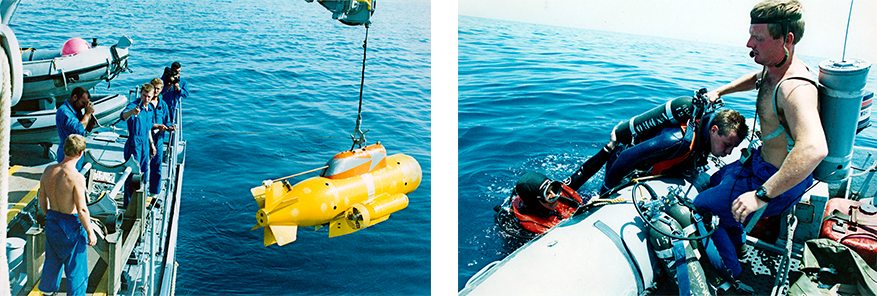

My next adventure was during the Persian Gulf “tanker war” in 1988. The French navy was on a sea mine hunting operation to detonate unexploded ordnance from the sea bottom. The mines had been laid by the Iranians during their 8-year war with Iraq to disrupt shipping activity in and out of the Gulf. It was towards the end of the conflict, which came to a halt in August 1988, that I spent a few days on a minesweeper combing the sea bottom. While I was aboard, the ship found and detonated three mines which was a welcome relief from the otherwise slow and monotonous life on a minesweeper.

The PAP (Possions Auto Propels) is being recovered from the sea and put on the deck of the Andromeda after it detected a mine stuck to the sea floor. Two French navy drivers are climbing back on the Zodiac after setting a charge next to the mine.

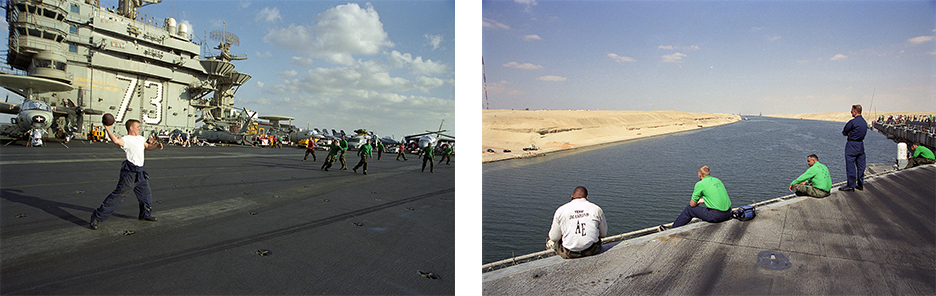

In addition to these two experiences, I covered other warships. However, none of those ventures could compare with my assignments on U.S. navy aircraft carriers. In all, I had the opportunity to board four carriers between 2000 and 2007. In September 2000, I was on the USS George Washington as it transited the Suez Canal on its homeward journey after taking part in operation Southern Watch aimed at maintaining the no-fly-zone in southern Iraq. During the 13 to 15 hours, it takes a ship to transit the Suez Canal, all military exercises are normally suspended. This was considered downtime for the crew on the USS George Washington who played American football on the empty flight deck or sat on the gunwale admiring the desert scenery. For many sailors, the time transiting the canal, or “The Ditch” as it is nicknamed, is a time for reflection, journaling, or writing letters to loved ones back home.

Sailors playing football on the empty deck of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington as it transits the Suez Canal. Other sailors sit on the gunwale and look out over the Egyptian desert.

On this 20th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, I can’t help but reflect on my second visit to an aircraft carrier, the USS Constellation. In February of 2003 the U.S. was in the process of bolstering its naval armada in the Persian Gulf for a possible assault on Iraq. The USS Constellation was part of that effort, but what was particularly significant about this voyage was that it would be the 43-year-old battleship’s last deployment before being decommissioned or, as one sailor termed it, “turned into razorblades.” Der Spiegel journalist Bernard Zand and I were lucky to be on this final journey.

The best time to photograph a jet taking off from the flight deck is just after sunset when you can still focus on the jet and at the same time see the red and orange afterglow from the jet engine.

Like all modern-day aircraft carriers, the USS Constellation was comparable to a town in terms of its capacity to house as many as 5000 sailors at any given time. It included numerous mess halls and kitchens which served up to 18,000 meals a day. In addition, there were convenient stores, lounges, gaming rooms, and gyms with exercise machines. When the flight deck was not in use, sailors could play sports or jog in that area although getting around the aircraft in itself was a workout especially when it came to maneuvering the narrow passageways and stairways leading to the different levels. There was a post office, laundry service, telephone exchange, as well as medical and dental clinics.

F-18 jets taking off on the flight deck of the USS Constellation.

The welcome package for journalists visiting an aircraft carrier always includes a tour of the warship. During the tour of the USS Constellation, Bernard and I noticed a room that looked like a jungle encampment. When I inquired about the camouflage, our guide said it had to do with a marine air squadron that had been assigned to the USS Constellation battle group. After we finished our tour, Bernard asked whether we could spend some time with the marines while they were preparing for night flight ops. After securing the commander’s permission we spent the remainder of the evening with the marines as they prepared for the night’s mission.

Keeping track of the aircraft on the flight deck of the USS Constellation using an “ouija board” with miniature model planes. The board is a replica of the flight deck and is used on every U.S. aircraft carrier (L). The actual flight deck of the USS Constellation.

It was no secret why the USS Constellation battle group was in the Persian Gulf conducting maneuvers. The tension between the U.S. administration and Saddam Hussein had reached such a peak that it wasn’t any more a matter of whether there was going to be a war, but rather when it was going to start. As the marines were preparing themselves, Bernard asked one of the pilots if they were planning to fly over Iraq. “That is top secret information!” replied the marine. Then he the added with a wink, “if you see me come out of the changing room with a handgun you’ll know where I’m going.” A few minutes later he returned with a 9mm Sig Sauer in his hand and slipped it inside his flight suit. With that final gesture we watched them make their way to the briefing room and then out to the flight deck.

A Marine pilot attached to the USS Constellation battle group takes a 9mm Sig Sauer hang and puts it into his flight suit before making his way to the flight deck. Der Spiegel correspondent Bernard Zand and I on the Flight deck of the USS Constellation.

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is considered one of the most hazardous workplaces, especially during flight ops. The noise is deafening; the smell of fuel and jet exhaust is dizzying, and the number of moveable parts is mesmerizing. Catapult cables launch fighter jets into the sky, while at the same time arrest cables are catching jets landing. Witnessing flight ops at night explains why it’s considered one of the most dangerous workplaces. Most communication is done by hand signals, and it’s only possible to know who is responsible for what by the color of the vest or jacket they are wearing. Sailors in charge of loading ordnance onto jets wear red, while those in green are responsible for the catapult and the arrest cables. Crew members in yellow are in charge of the jet’s movements on the deck while those in purple handle refueling etc.

A F-18 being catapulted off the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower

Before I was allowed to go onto the flightdeck I was given some essential equipment and strict instructions. After being outfitted with a white vest indicating that I was a guest or member of the press, as well as a helmet and ear plugs, I was assigned a crew member and told to stick with him and obey his orders. My first visit to the flight deck was at night during flight ops and the experience was overwhelming and unfruitful. By time I was able to settle in, make a proper exposure, focus, and take a few shots it was time to move on to the next location. In the end, I wasn’t able capture anything worthwhile and felt incredibly frustrated. Fortunately, I had another opportunity to visit the deck the next morning and I was able to take some good photos.

Landing a F-18 on the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower with the arresting hook dragging behind.

My next assignment aboard an aircraft carrier was in March 2006, a few years after Saddam Hussein had been deposed. This time Bernard and I visited the USS Ronald Reagan which had been dispatched to the Persian Gulf as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom, which was meant to stabilize Iraq following the 2003 U.S invasion. The interesting thing about this carrier was the amount of Ronald Reagan paraphernalia that it had on display, including a giant mural in one of the mess halls showing the former president on horseback at his California ranch.

Sailors wearing red are responsible for loading ordinance onto fighter jets.

The story we gravitated towards was Lieutenant Erin Flint, the first female pilot trained on the navy’s latest fighter jet, the F-18 Super Hornet. Bernard and I are both wristwatch aficionados and the first thing we noticed, when we met Lieutenant Flint, was the watch she was wearing on her wrist. For the most part military pilots nowadays wear wristwatches for show. Gone are the days when pilots were required to wear a specific watch that if needed could be a lifesaver if the jets instruments malfunctioned. Today, it’s common to see pilots wearing high end Swiss watches such as Rolex, IWC, Breitling etc. that have also had a long history with the aviation industry but come with a hefty price tag. Lieutenant Flint bucked that trend and was wearing a simple inexpensive Casio digital watch with a pink rubber strap. I think that she was a bit shocked that our first round of questioning was more about the watch she wore rather than about her very impressive accomplishments as a navy fighter pilot.

Lieutenant Erin Flint, the first female pilot trained on the navy’s latest fighter jet, the F-18 Super Hornet. Instead of wearing some expensive highbrow wristwatch she wore an inexpensive Casio.

While Bernard asked questions, I took photos of the lieutenant as she was suiting up and getting ready to fly. Since she was training on the new F-18 most of her sorties were training missions. After Lt Flint attended a briefing session with detailed instruction concerning their flight, we followed her out onto the flight deck where I took more pictures of her getting into the cockpit and making final preparations. Afterwards, I photographed her from the tower as she took off and landed on the carrier.

The after burn from the jet engine of an F-18 as it lifts off from the flight deck just after the sunset.

I recently looked up Lt Flint to find out what had become of her. I found that she was now Cmdr. Erin E. Flint, commanding officer in charge of the strike fighter squadron (VFA-131) based in Virginia Beach, Virginia. She is responsible for the squadron and sending jets and pilots to various aircraft carriers anywhere in the world. I’m tempted to write her and ask what wristwatch she’s wearing now.

The USS McCampbell patrols near the ABOT oil terminal inside Iraqi waters (L). An Iraqi soldier stands guard on the oil terminal while waiting tankers are filled up with crude oil.

Besides the USS Ronald Reagan, we visited the HMS Bulwark, a British amphibious assault ship. The Bulwark, which was designed to put large numbers of troops, vehicles, and equipment ashore using onboard landing craft, was on a mission to secure Al Basra Oil Terminal (ABOT), Iraq’s major offshore oil terminal. The ABOT is 15 kilometers offshore and coalition forces had recently foiled a suicide attempt by a small boat packed with explosives as it was speeding towards the oil terminal. We toured the terminal and accompanied the Royal Marines on a reconnaissance mission to intercept a small Arab dhow sailing inside the restricted security area. After boarding the dhow and searching the boat’s contents the royal Marines found only fish below deck. We also spent some time on the destroyer USS McCampbell which was taking part in protecting Iraq’s offshore oil installations.

Royal Marines take action and intercept a small fishing dhow that came into restricted waters near Iraq’s oil terminal. In the end all that was found aboard the vessel was fish and the marines let them go with just a warning.

The last assignment Bernard and I had together on an aircraft carrier together was in April 2007.That’s when we visited the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower while it patrolled in the Persian Gulf as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. By this time the situation in Iraq had taken a turn to the worse and U.S. ground forces were continually under attack by insurgent groups operating in Baghdad and the western Anbar province. To counter the insurgency George W. Bush ordered a troop surge for extra security. The Dwight D. Eisenhower was part of that surge giving the troops air support.

Action on the flight deck of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower

Like our previous visits to warships everything we did aboard was part of a strict program set by our hosts. Since this was my fourth visit to an aircraft carrier, I felt much more at ease photographing flight ops. By now I realized that the optimum time for the most dramatic shots was just after sunset when I could still focus sharply on the jets taking off and at the same time capture the afterburn or red, orange glow coming from the jet’s exhaust. I got to the point where I stopped trying to focus on the jet and instead focused on one spot on the runway where I wanted the photo to be the sharpest. This was how I was able to prevent the camera’s auto focus feature from ruining my shots as in the early 2000s the cameras’ tracking and autofocus mechanisms were not as advanced and precise as today.

Inside the air control tower of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (L). Flight deck crew aboard the USS Ronald Reagan walk the runway in search of any debris which could damage the jets taking off and landing.

Tom Cruise’s Top Gun legacy may have glorified the life of a US navy pilot, but judging from my experiences on aircraft carriers the pilots and crew are locked into routines which can become monotonous. The main focus is to follow protocols that maintain safety and security as top priorities. Yet, for a photojournalist like me who only visited for a few days at a time, the trip was exhilarating. From observing how these mega ships served as temporary homes to thousands of naval servicemen to documenting spectacular sorties especially at night, I consider that my coverage of warships in action was one of the highlights of my career. This experience honed my photography in action skills, and forced me to adapt to new environments including falling asleep while night flight ops were taking place just above my bed.