Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

The beginning of August marks the 30-year anniversary of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Considering the more recent wars and upheavals that have struck Iraq and the rest of the region, this conflict has slipped from our collective memory. However, the first Iraq war, as it is often called, marked a significant milestone in contemporary history with consequences that are still affecting the lives of millions of people.

My nearly yearlong coverage of the Iraq crisis began when I was on holiday in London in the early morning hours of August 2, 1990. At 03:30 I was woken up by a telephone call from the London photo desk of the Associated Press.

“Do you have a valid visa for Kuwait in your passport?” the photo editor on duty asked.

“Yes,” I replied, trying to wake up, “What time is it?”

“The Iraqi military has just invaded Kuwait and We need you to go to Kuwait City now!”

I made a few calls to Kuwait and realized it was already too late. Kuwait International Airport had been seized by Iraqi troops and by the time the sun had risen over London, Kuwait’s borders with the outside world had been sealed.

Kuwaiti Crown Prince Saad al Sabah, surrounded by security, appeals to hundreds of stranded nationals to remain calm, from the top window of the Kuwaiti Embassy in Cairo. Kuwaiti nationals, waving flags and holding portraits of Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Jaber al Sabah and Crown Prince Saad al Sabah, show their support for the Kuwait leadership outside the embassy. Thousands of Kuwaitis on summer holiday became refugees overnight after Saddam Hussein’s military invaded their country.

A few hours later I was on a plane, but instead of heading to Kuwait, I traveled to Cairo to help in AP’s photo coverage of the Kuwaiti crisis. Over the course of the following 10 months I was on the ground covering the events in Egypt, Jordan and Iraq.

Gulf War coverage in Egypt initially consisted of keeping track of developments at the Arab League. For the first time in the organization’s history, a summit of Arab leaders was convened in a matter of days. Suddenly, the decision makers of the region converged on the Egyptian capital. Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Jaber al-Sabah, already in exile in Cairo, appealed for a unanimous Arab voice against the invasion of his country. Like their leader, many Kuwaiti citizens vacationing in Egypt and other countries, had been stranded. The media nicknamed them “Cartier Refugees” because of their fancy designer clothes and top-of-the-line cars. Some hotels, like the Safir Zamalek, became known as “Little Kuwait.” A micro-economy even sprung up across the street from the hotel selling everything from “Free Kuwait” T-shirts to soft drinks imported from Saudi Arabia.

The Spanish frigate Santa Maria passes a derelict tank at the southern end of the Suez Canal. The USS aircraft carrier John F. Kennedy passes a mosque as it exits the canal. Both warships are en route to the Persian Gulf as part of a US-led coalition to liberate Kuwait.

When Arab diplomatic efforts failed to dislodge Hussein from Kuwait, the world community led by the United States began the largest international military buildup since the end of World War II. Every day, the Suez Canal witnessed a flotilla of warships sailing to the Persian Gulf.

In early September, I was asked to move to Amman to help cover the mounting refugee crisis as guest workers living in Iraq were streaming across the border into Jordan. Unlike the Kuwaitis in Egypt, the refugees in Jordan arrived penniless. Most came from poor Arab countries, the Indian subcontinent and from as far away as Vietnam and the Philippines. Upon their arrival in Jordan, they were housed in tent villages scattered around the country until arrangements could be made to fly them by plane to their countries of origin. It was heartbreaking to see these refugees, some who had toiled in Iraq for decades, arrive with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

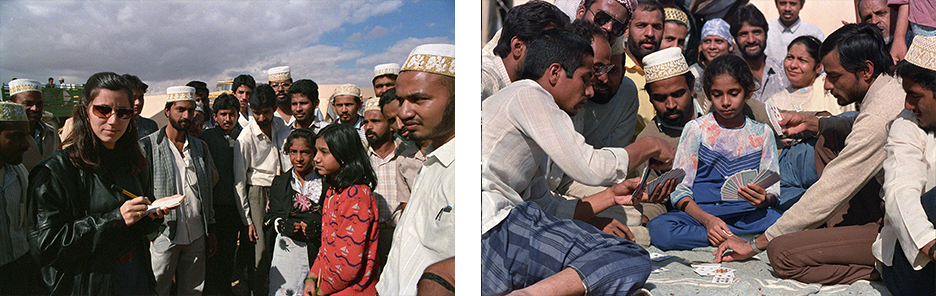

Associated Press journalist, Zina Hemady (L), interviews refugees from the Indian subcontinent who were forced to to leave Iraq and were housed at Azraq Camp in the desert outside the Jordanian capital, Amman. Refugees play cards at the camp.

Guest workers from the Indian subcontinent, the Philippines, and other countries streaming out if Iraq are housed in tent cities in the desert around the capital, Amman.

Jordan was also caught in a tug-of-war between its own Palestinian population and the allied coalition. Tensions escalated when Saddam Hussein said he would pull out of Kuwait if Israel withdrew from occupied territories in Palestine. Suddenly, there was massive popular support for the Iraqi president that Jordan’s King Hussein could not ignore. In an attempt to stabilize the situation, the monarch called for dialogue rather than a military confrontation. This was taken by the West and its Gulf Arab allies as being a conciliatory toward the Iraqi leader. As a result, Jordan’s Arab neighbors punished King Hussein by isolating his tiny kingdom and cutting off all financial assistance. The situation in Jordan became even graver when some 300,000 Jordanians and Palestinians expelled from the Gulf countries returned home.

Jordan’s King Hussein speaks to the press. As an advocate of dialogue and a peaceful end to the conflict, the monarch was ostracized by the West and its Arab allies. Behind the king is his son Abdullah (R) who succeeded to the throne in February 1999. Jordanian woman take to the streets of Amman to show their support for the king and Saddam Hussein.

Iraq had been out of bounds to most Western journalists since the invasion. Reports of what was happening in the country came from refugees and the selected few who had been able to travel back and forth. International concern centered on those western nationals being held in Kuwait and Iraq against their will. As the situation worsened many of the hostages were kept at military and other strategic sites in order to deter an allied attack, thus becoming known as “human shields.” In an attempt to defuse the hostage crisis, international figures including Yousef Islam (Cat Stevens), Nicaraguan ex-president Daniel Ortega, and celebrities sympathetic to the plight of the Iraqi people suffering under UN sanctions, traveled to Baghdad carrying medicine and other goods. In return they were able to leave with a token number of human shields.

Everyday outside the Iraqi Consulate in Amman, dozens of journalists from the international media would gather to see if their visas had been approved. No one knew whose turn would be next. Many young journalists working for a hometown newspaper got their big break when they were allowed into Iraq. When I finally I got my visa in early November, I flew to Baghdad where my first impression was that the city had not changed much since I had visited two years earlier covering the final stages of the Iran-Iraq war.

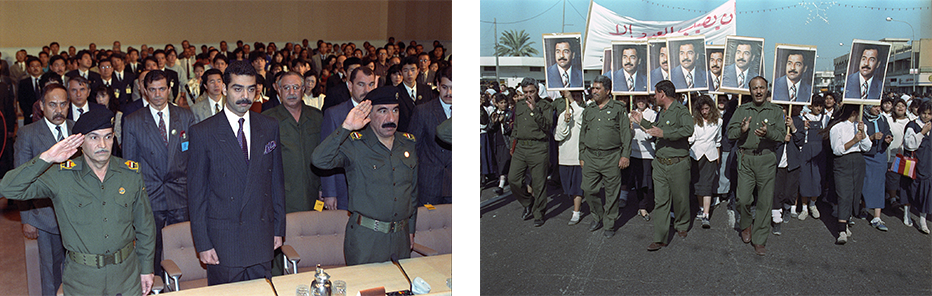

Saddam Hussein’s eldest son Uday stands for the national anthem. Iraqi soldiers lead school girls, holding placards of Saddam Hussein, on a parade through the streets of Bagdad.

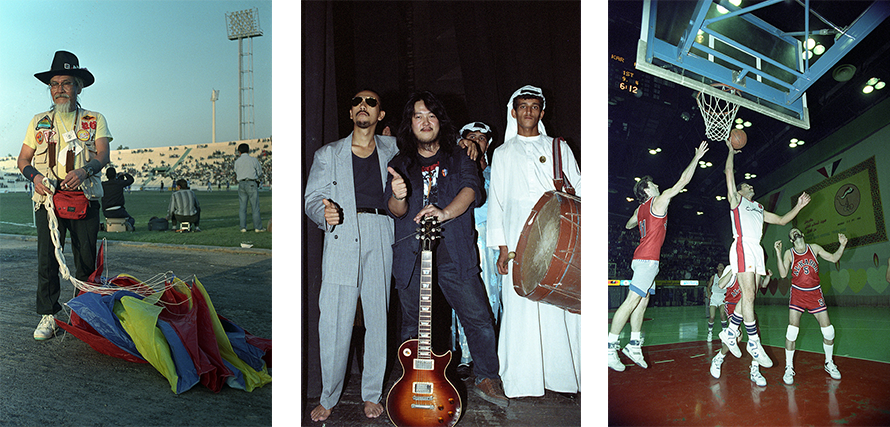

I arrived as intensified efforts were underway by the international community to secure the release of hostages held in both Kuwait and Iraq. As outside pressure mounted, the Iraqi leadership decided to host an international Music and Sports Peace Festival, under the patronage of Saddam Hussein’s eldest son Uday. What followed was a surreal carnival of “peace freaks,” retired liberal politicians, and fringe groups converging on the Iraqi capital. Housewives traveled from as far away as Japan and America to plead for their husbands’ or brothers’ release. The Japanese senator and former wrestler Kanji Inoki arrived with an army of wrestlers, heavy-metal rock musicians, kite flyers and other entertainers. From the U.S. came a group who claimed to be an all in one basketball/volleyball team as well as singing troupe. Even former heavy-weight boxing champion Mohamed Ali showed up with an entourage of assorted peaceniks and businessmen, one of which was more interested in promoting Ali Shoe Polish than solving the crisis at hand.

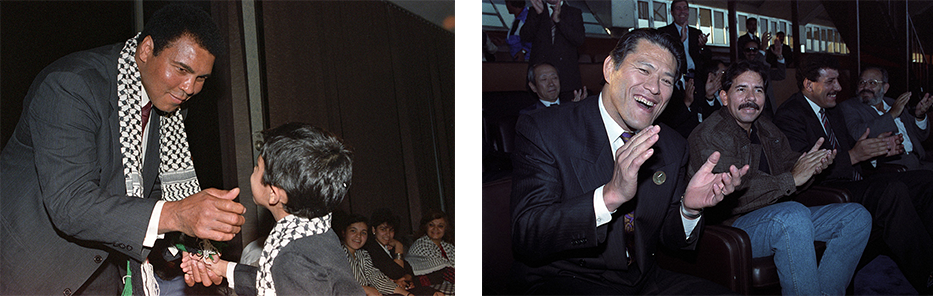

Former heavy weight boxing champ Mohammed Ali, wearing a Palestinian kaffiyeh, visits with Palestinian children who are living in Iraq. Japanese senator and former wrestler Kanji Inoki, who once fought against Mohammed Ali, sits next to Nicaragua’s ex-president Daniel Ortega at a soccer game in Baghdad.

For three days Baghdad rocked to the sounds of wrestlers pounding each other into the canvas, heavy metal bands, and bygone peace-chants. Uday, who was the center of attention, at this event glowed with pride as he listened to both politicians and housewives plead for the freedom of the “Human Shields.”

The festival climaxed with the much-anticipated basketball game between the U.S. and an Iraqi club team. Right from the beginning I could tell that things were not going to go well for the Americans, when the U.S. captain pleaded with me to join their team, as I was setting up to photograph the game. By halftime the Iraqi side had mounted such a substantial lead, so, to avoid embarrassing the U.S. team, the Iraqi captain decided to mix the two teams to make the game more balanced. After the game everyone came together, congratulated each other and posed for photographs.

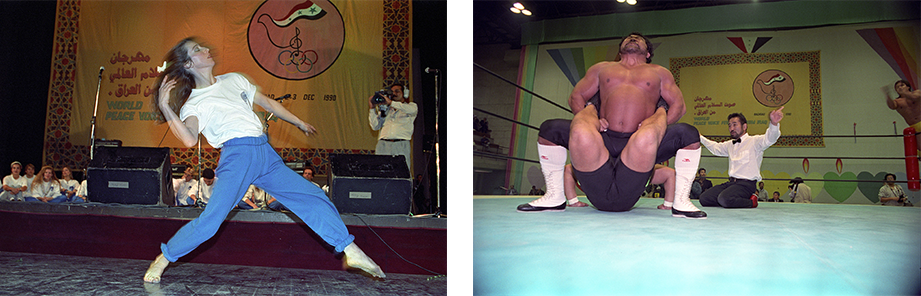

American peace activist and dancer Kathryn Skatula gives a dance performance, while Japanese professional wrestlers demonstrate their skills during the Music and Sports Peace festival in Baghdad.

Hideo Matsutani, a member of the Japanese Kite Association sets up his kite; members of the Japanese heavy metal band, Monjirou, stand alongside traditional Arab musicians, and US and Iraqi basketball teams play a friendly game.

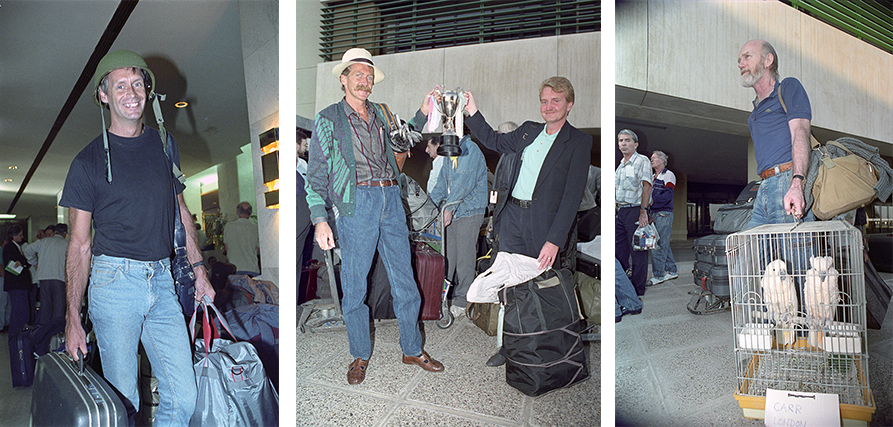

In the eyes of the Iraq hierarchy, the three-day festival proved to be a great success. Buoyed by this publicity stunt, parliament met in an emergency session a few days later and declared that the Iraqi military was now strong enough and ready to defend the “homeland;” therefore, all foreigners were free to leave.

For the month leading up to the Music and Sports Peace Festival, I was the only western photographer working in the country. Every evening, I would wander over to the abandoned U.S. Embassy to transmit my photos from the only international phone line that was mysteriously still functioning. One evening, I ran into a U.S. diplomat who was as surprised to see me as I was to see him. He never questioned my presence in the embassy, but his only comment was: “If war ever breaks out you won’t have to worry about paying your phone bill. But, if it doesn’t, then we’ll track you down and send you the bill.”

Westerners leave Iraq after parliament unanimously voted to free all hostages, held at sensitive site around the country. The men carry out souvenirs and trophies, as well as their cherished pets.

With the hostage crisis over, I focused my coverage on the plight of Iraqi citizens suffering under international sanctions. I spent days touring children’s hospitals, surgical wards and food distribution centers. Everywhere, the effects of the shortage of medicine and food were obvious. It felt like the country was in for a long winter as everyone knew that an invasion was not a matter of if, but when. By mid-December my visa extension came to an end and I was asked to leave.

When the bombing campaign started on 17 January 1991, I was high up in the Swiss Alps on a ski holiday. Returning to Amman, Jordan, I found the country filled with rage. Demonstrations against the bombing of Iraq were a daily occurrence. Everyone from the Palestinian refugees to the most educated intellectuals took their grievances to the streets. There was a time when, as a Westerner, I feared for my safety. Then came Hussein’s Scud-missile attacks on Israel, which did not amount to much of a military threat against the Jewish state but did succeed in defusing some of the tension in Jordan. As a precaution, we taped up the windows at the AP office when we realized that the Scud missiles had to fly over Amman to hit Israel and that their accuracy was questionable. After a Scud attack, Palestinians and Jordanians celebrated publicly and handed out candy to pedestrians in the streets.

Tens of thousands of Jordanians and Palestinians take to the streets of Amman in protest of the bombing of Iraq. Jordanians listen to a radio news broadcast out of Iraq.

Editing negatives at the AP office in Amman. We used a Leafax scanner and modem to send the photos over a telephone line. Staff at the AP office tape the glass windows in the event an Iraqi Scud missile aimed at Israel went astray.

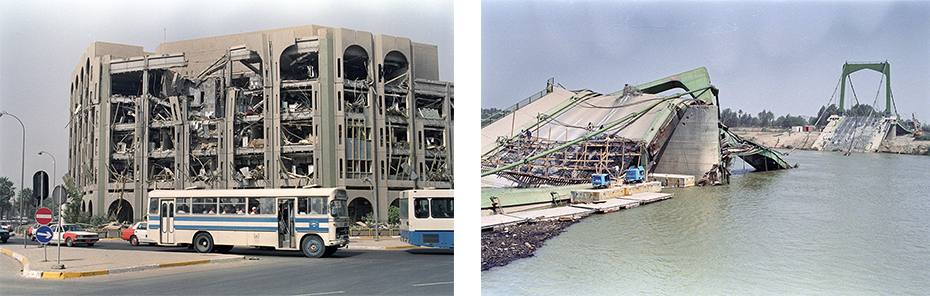

Shortly after the war ended, I was one of the first journalists to be granted an Iraqi visa. This time, an air embargo forced me to take the grueling 17-hour-long trip overland. It was not until I crossed into Iraq from Jordan that I realized the intensity of the allied bombing campaign of the countryside. Even in the middle of ·the desert, communication towers had been turned into twisted steel, and oil tankers, allegedly mistaken for Scud missile launchers, littered parts of the highway. In Baghdad, the bombing campaign had been more targeted with surgical strikes aimed at certain structures in crowed neighborhoods while other buildings remained unscathed. All the bridges that crossed the Tigris river, dividing the capital, were damaged to some extent. Because all communication had been cut, AP provided me with a satellite phone and a generator, but it was nothing like the satellite phones of today. That early version consisted of two very large heavy metal suitcases that had to be assembled. One suitcase housed the antenna dish, while the other one had the phone. Fortunately, the technicians at CNN were kind enough to help me set up and find a satellite signal. Transmitting photos was a very timely and an expensive endeavor. Sometimes it would take me up to an hour to send one black and white image. Over a regular phone line, the same image takes than ten minutes.

A government building and a bridge crossing the Tigris river are completely destroyed following the allied bombing of Iraq.

An Iraqi mother sits next to her infant at an Iraqi hospital. Iraq suffered from an acute shortage of drugs and medical supplies after the war. Stereos, cameras and other electronic goods stolen from Kuwait are sold at Souk al Harameya or Theives’ Market in the center of Baghdad.

Considering the damage caused by the coalition bombing, life on the streets of Baghdad seemed to carry on relatively normal. In the center of the city, near Tahrir square, a parking lot had been turned into a giant outdoor market called Souk al Harameya or Thieves’ Market, which was full of stolen Kuwaiti goods brought back by retreating Iraqi soldiers and civilians. One could find everything from electric organs, TVs and cameras, to gold Rolex watches with many of the items still showing the original price in Kuwaiti dinars.

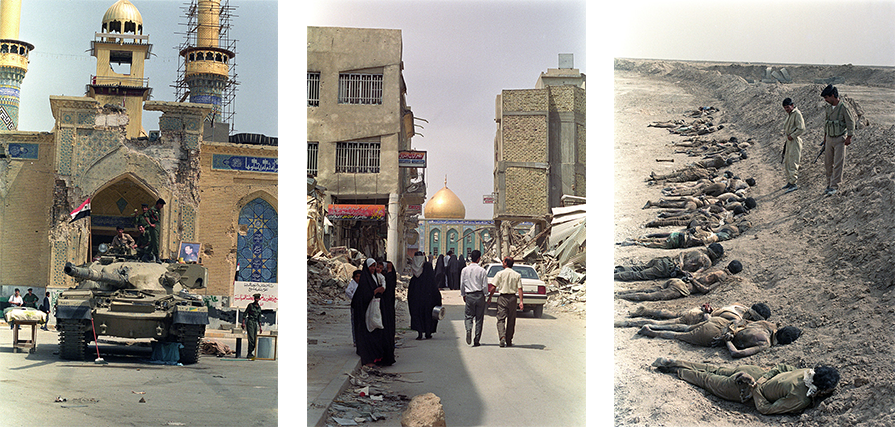

An Iraqi tank is positioned at the entrance of the heavily-damaged Imam Abbas Mosque in Karbala, southern Iraq, after fighting broke out between Shi’te Moslem rebels and the Iraqi Army. A street in the center of Karbala, leading to the Imam Abbas mosque, bares scars of heavy fighting. Dozens of Iraqi government soldiers lie dead near the border with Iran. The soldiers were captured, blindfolded and executed by Iranian- backed Shi’te rebels.

Now that the war had ended and Kuwait liberated, Iraq found itself embroiled in a civil war. In the south, the Iraqi armed forces were fighting against Shi’ite Moslem insurgents, and in the north, they were at war with Kurdish separatist. The leadership was eager to show the outside world that they were in control of the entire country. Nearly every day, the ministry of information would take the international press on government-sponsored trips to either of the two hotspots to show that the fighting only amounted to minor skirmishes. In all the towns and cities that we visited, Iraqi soldiers looked to be in control, but it was obvious that significant fighting had taken place. The centers of Karbala and Najaf, the two holy Shi’te Moslem shrines, had been so shot up that they resembled Swiss cheese. In the Kurdish north, terrified refugees wandered the countryside, living in make-shift camps. In order to deceive the visiting press, Iraqi soldiers would hand out food, claiming that these civilians were fleeing internecine fighting within the Kurdish ranks. Above the town of Sulaymaniyah, we were taken to a shallow grave that was being unearthed. Inside lay hundreds of dead Iraqi soldiers, most of whom had been shot at close range after being captured by Kurdish separatists. Towns like Erbil and Dahuk were all but abandoned, save for the women, children, and the elderly who roamed the streets in search of food. During my entire time in the north, there was never any sight of young men. It seemed all the men aged 16 to 40 had vanished.

Internally displaced Kurdish refugees, mostly women and children, are rounded up by Iraqi military in northern Iraq and taken to camps.

The Iraqi army uncovers a shallow grave full of hundreds of dead Iraqi government soldiers who were captured and executed by Kurdish separatists above the northern Iraqi town of Sulimaniya.

Back in Baghdad, there were shortages everywhere. The once abundant buffet at the al Rasheed Hotel had dwindled down to little more than cheese, dates, and bread. The lack of amenities was evident even in the best hotels where dark corridors became the norm. The Iraqis were relieved that the war was over, but with each passing day, many found themselves becoming poorer as the Iraqi dinar quickly collapsed against the dollar. People lined up at money exchanges to buy dollars and at immigration offices for exit visas. The government, fearful of a mass exodus, restricted those who could travel abroad.

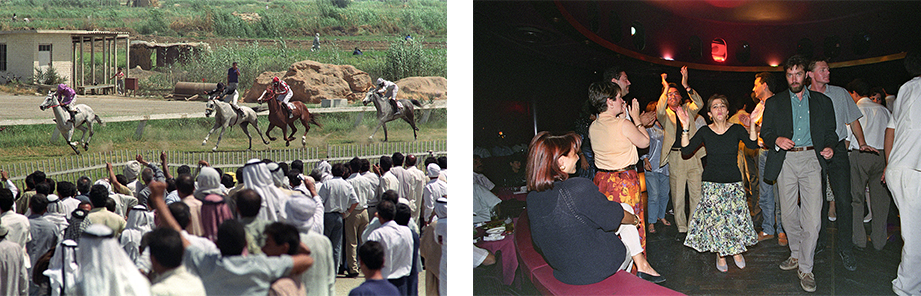

In May, I returned once again but this time it felt that Baghdad was slowly on the road to recovery. Reconstruction was going on everywhere, including the bridges that connected the city, and people had adapted to life under the U.N. embargo. Although hospitals, schools, and factories were all suffering from lack of equipment and supplies, Iraqis were beginning to go out and socialize again. In the evenings, the coffeehouses were full; families ate at restaurants on the banks of the Tigris, and even the weekly horse races started up again.

Life in Baghdad slowly begins to go back to normal three months after the allies halt their military campaign against Iraq. Coffee sellers are back in business and carpet dealers sell plastic rugs honoring Saddam Hussein.

One evening, I went down with a group of friends to the disco hoping for a diversion. By then Saddam Hussein had placed a ban on selling alcohol in public places but, for reasons which became obvious, the al Rasheed disco was excluded. After an extensive dinner of Arab mezza accompanied by substantial quantities of Johnny Walker Black Label, it was time to hit the dance floor. As this was the only night spot still open, Baghdad’s high society was out in numbers. Men and women danced to the Arab beat oblivious to the hardships that the rest of the country was facing. At one point, I looked around me and realized that there were only men on the dance floor. As I walked over to join my friends at their table I asked, in a loud voice, where all the women had gone. My Iraqi friend motioned me to come close and keep my voice down; then he pulled me even closer and whispered in my ear, “Don’t make it obvious when you turn around, but the party-pooper and his cronies have arrived.” In the corner of the room sat Uday Hussein with some male companions.

The weekly horse races are reintroduced a few months after the war ended. Even though alcohol was officially banned there was no lack of it at the Al Rashid Hotel disco and bar.

By then the world had grown tired of Iraq. For the previous ten months the press had been bombarding its audience with nothing else. The media was now looking for another story, another crisis to report on. One evening, just as I was about to turn off the generator that powered my satellite phone, the phone rang. “I think it’s time you high-tail it out of Iraq, we need you in Ethiopia,” my editor in London said. “What’s happening there?” I asked. “Another coup d’etat!”

Amiriyah Shelter Bombing 30th Anniversary - NEGATIVE COLORS

[…] Gulf War Snapshots 1990 – 1991 […]

Awesome reporting! Photos amazing! I love reading your reports and seeing the amazing photos you take.

The 30 Year Anniversary of Iraq's Civil War - NEGATIVE COLORS

[…] Gulf War Snapshots 1990 – 1991 […]