Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

Thirty years ago, I boarded a Canadian military transport plane from Nairobi, Kenya to the southern Somali town of Bardera. The Canadians had recently joined the United States, France, Germany, and Belgium who were leading an international campaign to airlift much needed emergency food and relief supplies into the country which was reeling under the effect of a civil war coupled with a drought.

As no transponders were working at any airport in Somalia, Canadian Hercules C-130 crews had to rely on maps to find the dirt runway near Bardera.

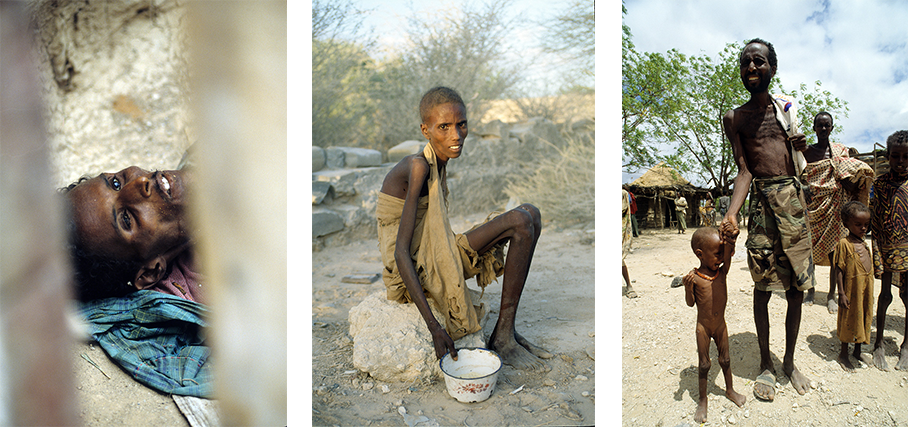

In January 1991, less than two years before I arrived with reporter Michael Georgy, Somalia’s longtime dictator Mohammed Siad Barre had been toppled by rebels, and the country had slipped into chaos as it came under the rule of warring militias. Besides the civil strife, Somalia was going through one of its worst droughts in its history. By the time we arrived in Bardera, in September 1992, starving Somalis were migrating en masse from the rural areas to towns like Bardera, Kismayo, and Mogadishu where food distribution centers had been set up by the World Food Program (WFP) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). According to the United Nations (UN), which was at the head of this campaign, hundreds of thousands of Somalis had already died since the war started and another two million, out of a population of seven million, were on the brink of starvation.

A Canadian C-130 landing on a dirt runway near the town of Bardera in Southern Somalia. Unloading sacks of maize meal.

After landing on a dirt airstrip, we watched as a local organization with ties to regional warlord General Mohammed Farrah Aidid, unloaded the relief supplies and then accompanied the transport trucks to a distribution center just outside Bardera. At the center, it was utter chaos as crowds of women of all ages, some dragging themselves while other carried their emaciated babies, scrambled to reach the trucks where burlap bags of maize meal were being unloaded. Boys from the local militias were beating back the women with sticks and whips. The entire scene was total madness as babies and the weak were being trampled on in the melee.

Pandemonium breaks out at a feeding center near Bardera as the trucks carrying maize meal are unloaded. A young militia member beats back a starving refugee with a stick.

From Bardera we accompanied a truck to Doblay, a small village some 30 kilometers to the north where the residents were too weak to leave. Compared to the chaos that we witnessed in Bardera , the operation in Doblay seemed under control. Most of the villagers were too sick to leave their homes, and the ones who did come out to greet the trucks just stood and stared blankly while the food was being unloaded. As I walked around the village to find the remaining inhabitants, I fell on a man lying dead on the floor of his home. Sadly, the food aid had come too late for him and most residents of this small hamlet.

The only people left behind in the tiny hamlet of Doblay were the dead, the dying, and the destitute.

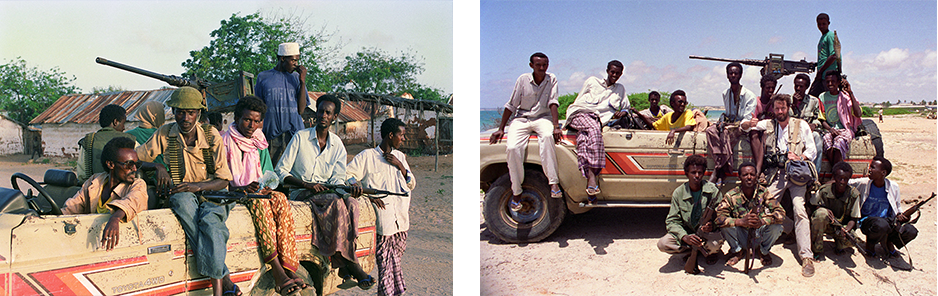

From Doblay Michael and I returned to Bardera to meet with Aidid, who controlled the town and much of the southern part of the country. At that point, Somalia had been pretty much divided between Aidid and his archrival Ali Mahdi Mohamed whose forces were locked in a vicious fight over control of the entire country. There were other warlords, but Aidid and Mahdi were the most powerful.

We had to stop often along the 30km track to Doblay to clear the way so that the truck carrying maize meal could progress. During the journey we passed starving refugees walking en masse towards bigger towns in search of food.

We headed to a heavily guarded two-story compound to meet Aidid who was waiting for us in a large room with an open layout. As soon as we entered we felt as if we had stepped into a kaleidoscope. The floor was covered with a multi -toned grey, white, and brown carpet while the walls were lined with bright red and white Yemeni-style floor cushions or mafrash. We sat down on the mafrash to interview Aidid who appealed for more food aid, but was strongly opposed to additional UN troops other than the 500 Pakistani peacekeepers already stationed in the capital Mogadishu. “There is no need for any more troops,” he said. “We consider this to be a Somali problem.” As expected, his opponent, Mahdi Mohamed, had taken the opposite stand welcoming more UN troops on the ground.

Warlord General Mohammed Farrah Aidid at his compound in Bardera.

After spending the night in Bardera we attempted to fly out with the Canadian air force, but their Hercules C-130 transport plane was being repaired. We waited around on the airstrip most of the day and watched as Canadian mechanics worked tirelessly on the engine to fix it. As it was getting dark, we lost hope of flying out that day, but fortunately, just as the sun was setting, the engine kicked in and we were able to take off for Nairobi in neighboring Kenya.

Aidid’s militiamen watch as the Canadian crew work on the grounded C-130. At sunset Aidid’s men show up with an armored personnel carrier mounted with an anti-aircraft gun for protection just incase we are forced to spend the night. Fortunately, the crew managed to get the engine running and we were able to liftoff.

After filing our story and regrouping for a few days, Michael and I made arrangements with the ICRC to visit their operations in the southern coastal port town of Kismayo. We set out on another Canadian C-130 cargo plane carrying supplies and were met on the dirt runway outside Kismayo by Colin from the ICRC who accompanied us to the compound. Colin was a seasoned relief worker from Ireland with many years of experience operating in conflict zones. He also understood that journalists had a different mission than aid workers and were on the ground to report events as they witnessed them. However, Colin’s French and Swiss colleagues were not as understanding. They were uncomfortable with our presence, which apparently hadn’t been announced, and were concerned that we would report what they considered to be sensitive information.

Children who had lost both parents were by far the most venerable. These two sets of siblings are the only surviving members of their families.

We later found out why hosting journalists in an aid camp was controversial. After touring Kismayo with Colin who showed us the lay of the land, we returned to the compound just after sunset and walked straight into a surreal scene that I will never forget. A candle-light sit down dinner was being served to the sound of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. The meal consisted of a traditional Swiss Cordon Bleu, meat stuffed with ham and Gruyere cheese, a side dish of cooked vegetables, and a green salad. The food was paired with a bottle of red wine and a chilled bottle of white. It felt like we were dining in the Swiss Alps rather than the misery of rural Somalia.

Destitute refugees waiting at a food distribution center in Kismayo. The boy (R) is holding his younger sibling who is close to death.

After dinner, I attempted to walk to one of the corner kiosks to buy a pack of cigarettes. Since the shooting had quieted down, I thought it would be safe to wonder out int the streets. The minute I stepped out of the compound, I was surrounded by at least ten heavily-armed Somali guards hired by the ICRC who demanded to know where I was going. When I explained the reason for my expedition, the entire group escorted me about 20 meters down the street to a guy selling cigarettes.

On my return, Colin offered to take Michael and I to the rooftop since smoking was strictly forbidden inside. When I walked over to the edge to take a look at the view, Colin gently pulled me to the ground as rebels were known to take potshots at silhouetted figures at night time assuming they were members of a rival gang. The three of us finished the evening in a sitting position in the open air, talking, smoking, and listening to gunfire erupting in various parts of the town.

Our gang of “technicals” who accompanied us during our stay in Kismayo.

A very well-organized feeding center in Kismayo run by a foreign aid organization.

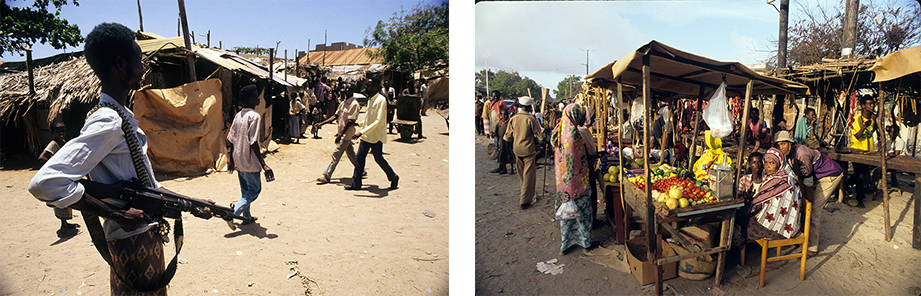

After some negotiations, we set out to explore the area. For one hundred dollars a day we secured a beat up Land Cuiser and a dozen or so heavily-armed guards ranging in age between the early teens and mid 20s. The feeding center that we visited on the outskirts of the town was far more organized than the one in Bardera. The refugees patiently sat on the ground in a circle, while waiting for their turn to receive their ration which consisted of a high protein milk substance for severely malnourished children and a porridge mixture for the adults. Next, we headed to a camp that had been set up along the beach. The refugees there had walked from the interior and were living in hovels made of sticks, wood planks, plastic, and anything else they could find. Besides their dire situation, these displace Somalis had no protection and were vulnerable to attack by the various militias that roamed the area.

Refugees who could make the trek walked from the interior of the country to Kismayo in search of food. They set up camp just outside the town and built shelters with whatever they could find.

Our own security detail left a lot to be desired. The militiamen in charge of our protection were allied with Aidid, the warlord with whom we had spent time with in Bardera. When we crossed into areas controlled by Mahdi’s gang, or sectors considered no-man’s-land, the tension among our bodyguards was palpable. The dozen “technicals” who accompanied us for two days were armed to the teeth with every conceivable weapon including AK-47s, rocket propelled grenade launchers, and an anti-aircraft gun that was mounded on the back of the Land Cruiser. How we all managed to squeeze in was a miracle, but what made things easier was that the vehicle had no windows or roof. It was just a matter of hanging on somewhere and praying that the driver did not hit a road bump or a pothole, or make a sharp turn.

Touring the marketplace in the center of Kismayo on foot with our armed guards.

Besides covering the feeding centers and refugee, we did manage to see another side to Kismayo. Our “technicals” drove us to the town center and took us on a walking tour of the marketplace which was bustling with normal life activity. We then took a coffee break in a café owned by an elderly Italian man who was born in Kismayo where he had spent his entire life. The café owner told us that he had only visited Italy once when he was very young, but that Kismayo was his home, no matter the hardships. He served us cappuccino with camel milk and then I took photos of him with our “technicals.”

Our “technicals” enjoying coffee with camels milk and then posing for photographs with the café’s Italian proprietor who had spent his entire life in Somalia.

Although our visit was brief, lasting about a week, we were left with the impression that things could only get worse. Three months later, Michael and I returned to Mogadishu to cover the U.S.-led military intervention aimed at creating safe zones and securing deliveries of food aid. Unfortunately, what began as a humanitarian gesture turned into political morass when the U.S. decided to take sides and go after Aidid. The major battle that resulted from this decision took place on 3 and 4 October, 1993. Its events are chronicled in the book, Blackhawk Down, which became a blockbuster movie with the same title. After the two days of fighting between the U.S. and Aidid’s forces, 19 U.S. servicemen and approximately 1000 Somalis, including civilians, were killed. Aidid went on to declare himself president of Somalia in 1995, but died a year later from a heart attack while recovering from a bullet wound.