Photographs and Text by Norbert Schiller

After successfully documenting the rarely visited oases of Siwa and Qara in Egypt’s Western Desert for my book, Egypt Beyond the Nile, my next mission was to find the Roman forts near the oasis town of Kharga. I had attempted this journey with two friends a decade earlier, but it had failed miserably as traveling on foot in the late spring desert heat proved to be an impossible and dangerous feat. The one memory that stuck with me was staggering back to Kharga, after wandering the desert for three days, with an empty ten-liter jerrycan strapped to my back and stopping at the first kiosk to gulp down five cold Fanta soft drinks back-to-back.

Trekking through the Wester Desert, in May 1985, with two school friends, Dirck Lyon (L) and John Warren, in search of the Roman fort of Qasr el Labeka. After three days of wandering in 40 degree Celsius temperatures, we returned to Kharga empty-handed.

I decided to attempt this adventure for the second time in the autumn of 1994, but for this trip time I had to make sure that I had made all the necessary preparations. Besides securing a decent mode of transportation, in the form of a Jeep Wrangler provided by a car rental agency with whom I had made a deal, I needed travel companions who had the knowledge and stamina for this journey. Patrick Godeau, a friend and fellow photographer who had previously joined me on the trip to Siwa and Qara, was on board. However, we also needed someone who had researched the Roman sites that we were hoping to locate. That’s when I called Robert Jackson, also a close friend and a desert explorer, asking him if he would be willing to join us. Robert and I met in 1981 when we were both exchange students at the American University in Cairo. Back then, he had already started trekking across Egypt’s deserts on foot and later on camel back. Although he was working full-time as a history teacher, Robert immediately agreed to join our expedition. When we arrived at his home in Cairo’s suburb of Maadi, Robert was sitting on a large icebox. He proudly explained that he had packed sandwiches, cold cuts, cheeses, fruit, and a few bottles of imported wine. My gut reaction was that these provisions were more suitable for an overnight camping trip than a weeklong photo expedition into Egypt’s Western Desert, but I didn’t want to burst his bubble. As I had predicted, we proceeded to devour most of these delicacies within 24 hours, before they spoiled in the desert heat. Afterwards we fell back on the staples that Patrick and I had packed which consisted of dates, peanuts and tequila.

A produce market and the town center at Kharga. This settlement feels more like a town in the Nile Valley than a quaint oasis in the middle of the desert. Since it had been established as the capital of the New Valley governorate, Kharga had a more developed infrastructure than all the other oasis towns and villages.

We drove for 8 hours to reach Kharga, the capital of the New Valley, and the largest Egyptian governorate which lies 600 kilometers south of Cairo. It is quite large for a provincial town and feels more like a sprawling city than a remote oasis. Robert, who was working on his own book At Empire’s Edge: Exploring Rome’s Egyptian Frontier, was an expert in desert travel and had already visited some of the fortresses that we were trying to locate. With his experience, the help of a compass, and Cassandra Vivian’s Islands of the Blest: A guide to the Oases and Western Desert of Egypt and its rudimentary maps, we set out across the rugged desert terrain to find a series of forts that dot the Kharga Depression. The Romans built their settlements in strategic locations along caravan routes with reliable sources of ground water. This way, the soldiers maintaining the forts could control and tax goods coming into Egypt and guard the settlements against possible attacks. These remote forts and settlements reached the height of their development and activity between the late Roman and early Byzantine periods (late 3rd through 5th centuries AD). Although the Romans were responsible for this expansion, the sites themselves, and the routes that linked them, show evidence of use dating back to the Neolithic period.

This utility pole is slowing being swallowed up by sand, while this paved road from the 1950s or 60s is being uncovered. As the wind is constantly shifting sand dunes from west to east across the Western Desert, some objects get buried while others become visible.

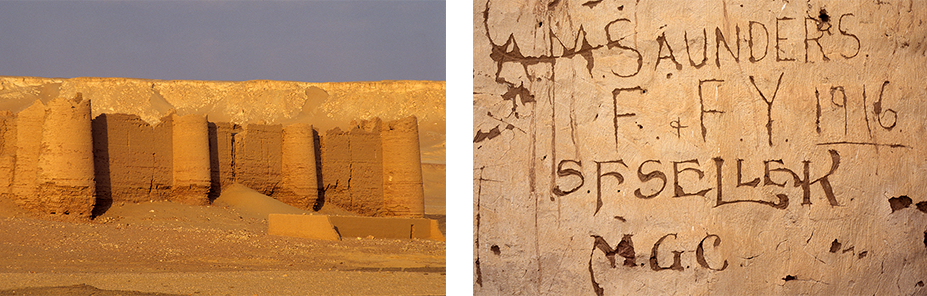

El Deir or “monastery” was the first settlement we reached. It’s a stunning Roman fortress located northwest of Kharga, not far from one of Egypt’s most notorious and remote prison complexes. After the fort had been abandoned by the Romans, it was most likely used by Egyptian orthodox monks which explains the origins of its present name. The walls are scribbled with graffiti scratched by British soldiers who were stationed there during WWI to protect Kharga from attacks by Sanusi tribesmen. The Sanusi, originally from Sudan and Libya, were coaxed by the Germans and the Ottomans to attack British and Italian interests in Egypt, Sudan and Libya.

The Roman fort at el Deir at sunset. The fort was later occupied by Coptic Orthodox monks taking refuge in the desert. Names of British soldiers who were stationed here during WWI can be seen scratched on the walls.

Our next destination was Qasr el Labeka, the Roman fort that I had originally set out to find on foot. Since GPS technology had not yet been introduced to Egypt, it took a great deal of time and patience to locate these forts as roads were nonexistent. After turning off the paved road, we proceeded with caution navigating our way over sand dunes and following desert tracks left by other vehicles. Some of the tire tracks date back to the 1920s when the first explorers using automobiles set out on desert expeditions. The oldest tracks, which are preserved beneath the sand dunes, occasionally become visible again when the wind blows away the sand revealing the desert pavement or reg, a hardpacked gravel and stone mixture.

A sand dune is seen rising above the reg, the dark brown desert pavement. As the mound shifted positions, it revealed the compressed gravel and stones that lay underneath it. A succulent grows out of the cracked desert surface after a rain storm.

Driving through the desert takes a great deal of skill and it’s advisable to travel in a convoy of at least two vehicles. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the luxury of hiring another Jeep, but I always followed two golden rules when undertaking such trips. One was to carry an extra jerrycan of water and the other to always remain within a two days’ walk from a major road.

The Roman desert fort of Qasr el Labeka, with its small palm grove, sits near the base of the escarpment.

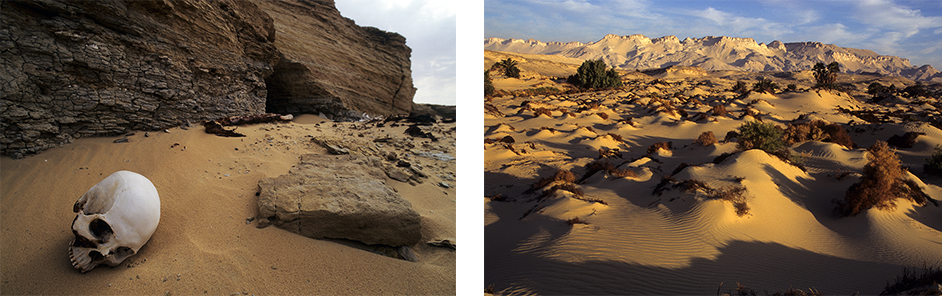

Qasr el Labeka is one of the most picturesque Roman desert forts. It’s located about 40 kilometers north of Kharga, below the escarpment that encircles the Kharga Depression. Unlike many of the other settlements in the deserts, where the water has dried up, Qasr el Labeka still has considerable groundwater and, as a result, is surrounded by vegetation and a small palm grove. Unfortunately, we arrived after dusk and were unable to take any photographs. However, at first light ,we went out to take pictures and then spent the day exploring the surrounding area which included a series of tombs, most probably Roman. At sunset, which provides the ideal setting for spectacular photographs, we moved quickly and strategically to capture the angles that we had in mind. The first photo on my list was of the Jeep Wrangler beside the fort taken from a nearby hill, as I had promised to provide photos to the company that lent me the vehicle. Robert, who was the designated driver, picked me up and drove us to the palm grove where Patrick was waiting. After taking our photos there, we drove to the last location on another small bluff for our final shoot before the sun disappeared. The plan worked out perfectly, and, as a reward, we celebrated that evening by finishing the last of Robert’s cold cuts and wine.

A skull from the tombs near Qasr el Labeka, which date back to Roman times. The desert landscape near the fort.

The consequences of driving over the soft leeward side of a sand dune versus traveling over the hard packed windward side.

The fort of Ain Um Dabadib lies roughly 18 kilometers west of Labeka, but the drive there proved far more challenging because of the sand dunes along the way. The trick to negotiating sand dunes is to stay off the soft leeward side of the dune, which faces away from the wind, and drive over the windward side that is constantly being hit and packed down by the wind. Our efforts paid off as catching our first sight of Ain Um Dabadib from afar will forever be engraved in my memory. Cassandra Vivian, who first visited this fort in 1989, describes her impressions in her unpublished autobiography as follows. “I cannot tell you the joy of sitting in the front seat of a 4×4 and turning off the asphalt road into the desert in quest of ancient buildings. This desert is so rich in history you would think it was a metropolitan area…That is what awaited us as we traveled up and down dunes for kilometer by kilometer until we spotted the majestic fort in the distance. There is nothing like it in the rest of the Egyptian desert.”

Patrick (L) and Robert set up for an early morning photo shoot of the Ain Um Dabadib fort.

The Roman settlement of Ain Um Dabadib must have had hundreds, if not thousands, of inhabitants in its heyday. One clue to the site’s prominence is the 15-kilometer man-made underground aqueduct leading to the base of the escarpment at this location. Robert, who had previously visited these ruins, was keen to see how far we could walk through the aqueduct given that much of it had collapsed. After walking for a few dozen meters, we came to a point where both the walls and roof had collapsed. As our attempts to dig through the sand and debris proved futile, we climbed back out and walked along the top hoping to find another entrance, but our efforts were futile.

A hole in the ceiling of the 15 kilometer aqueduct. Robert, wearing a headlamp, attempts to navigate through the narrow aqueduct that once brought water from the base of the escarpment to the settlement of Ain Um Dabadib.

Our next quest was the isolated and tiny settlement of Ain Amour, or Spring of the Lovely, which is 40 kilometers as the crow flies from Ain Um Dabadib. The trip, which should have taken a few hours at best, lasted nearly the entire day due to the sand dunes. When we finally arrived at our general destination, we still had to find the fort. Unlike all the other forts, Ain Amur is not located at the base of an escarpment but sits a little way up on a ridge making it impossible to see from below. As the sun sank, we scrambled up wadis or gullies on foot looking for the ruins. When we were just about to call off the search and set up camp for the night, we spotted the collapsed Roman stone structure near a small open spring . The view from the fort’s hilltop location was spectacular and I could just imagine how this spot would have been a perfect location for Roman soldiers to monitor caravan activity in the valley below.

Patrick climbs up a ravine in search of the remote Ain Amur settlement. The water spring of Ain Amur covered in greenery.

What makes the spring at Ain Amur so unique that it’s not found on the desert floor at the base of the escarpment where ground water is normally found, but part way up on a ridge. Robert was excited to try out his portable water purifier, but thankfully we did not have to depend on it because it took over an hour to produce a single cup of clean water. A year later, Patrick and Robert made the same trip between Qasr el Labeka and Dakala oasis on foot carrying all their supplies on their back. The trek took seven days, and luckily they were able replenish their water from the spring at Ain Amur using the same portable water purifier.

The settlement complex of Ain Amur with its spring and the view over the desert valley.

After spending two nights in Ain Amur, it was time for the final leg of our off-road adventure which would be ending at Dakhla oasis. The one obstacle that lay ahead was driving the Jeep from the valley floor up the escarpment. To prepare for our climb, we drove along the escarpment base looking for ravines which would be wide enough for the Jeep. Most of the gullies ended in sheer cliffs, but, after an exhausting search, we found one that looked doable although it had a steep incline and was rocky towards the top. After digging out the jagged rocks near the summit that could block our path, and unloading all our supplies, we were ready. Robert backed up the jeep as far as possible to get a running start and slammed his foot on the accelerator. On his first attempt, he made it up over the ridge, but punctured a tire in the process. Once that was fixed, we walked up and down a few times carrying our supplies to the top of the hill and were ready to hit the road. For the remainder of the drive, we followed Darb Ain Amur, an ancient caravan route, that led us across the plateau and down the other side until we could see the lights at Dakhla oasis in the distance.

Changing a punctured tire after driving up the escarpment. The imprint of the Darb Ain Amur, a camel caravan trail that had been used since ancient times.

From Dakhla oasis, we drove through the night on a poorly paved road back to Kharga from where Robert returned to Cairo and his day job. Patrick and I rested and resupplied for a day in Kharga before setting out on our next photography expedition.

Norbert, you are an amazing photographer and writer.

Loved this Norbert! Please share more!

Beautifully done old friend. Would love to join you on another adventure soon. Stay well.

Norbert, reading your recollections and seeing your photos brings back a kaleidoscope of happy memories of our desert adventures. I think sometimes that I should like to return to the Roman sites, and I would probably do so if given the chance, but not without trepidation. In those days virtually nobody knew of them. One had to work hard and take considerable risks to find them, and their beauty was rendered more poignant because of their remoteness and the air of mystery that surrounded them. Beneath centuries of sand, they retained their secrets inviolate. Today, most of them have been surveyed and systematically excavated, and although we have gained knowledge from those efforts, something precious was lost in the bargain. With their shovels and picks and grids and buckets, archaeologists have laid bare what time hid and protected, and after extracting every bit of data from their siftings, the soul-less remains are now left to crumble into oblivion or become tourist sites. For me, it was that soul, that audible whispering of ancient voices that bestowed such enchantment upon those mud-brick ruins. Were I to visit them today, I should lament their silence.