Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

The Battle of Tsorona – March 1999

Eritrea’s capital, Asmara, is like no other in Africa. There are no sounds of traffic, or smell of exhaust fumes. There are no beggars and no garbage. The mornings are crystal clear and the air is fresh. From my hotel balcony, Asmara looks more like a provincial town somewhere in Italy than the capital of one of Africa’s poorest countries. Italian-style architecture can be seen everywhere, from the corner gas station to office and governments buildings that grace the palm-lined boulevards. On the streets, there is no sense of rush. People walk leisurely and ride bicycles, take time out to chat with friends and enjoy cups of espresso at outdoor cafes. The day starts early with employees of the public and private sectors already in their offices by 8:00 a.m.

The palm-lined main street running through the center of Asmara. An Art Deco gas station from the 1930s.

Eritrea’s President Isayas Afworke

At nine o’clock my phone rings. A man from the Information Ministry asks if I want to join a group of journalists going to the battlefront at Tsorona, 120 km southeast of Asmara. Eritrea and neighboring Ethiopia have been at war over a border dispute since May 1998. Eritrea also claims that Ethiopia wants to topple its head of state, President Isayas Afworke. I accept the ministry’s invitation and rush to get ready. The planned time of departure is in a half hour. Having already been in Asmara for two days, I have a hard time believing that there is a border war raging only a few hours’ drive away from the capital. Evening newscasts and daily news bulletins bring home the fighting. However, Asmara still seems like a peaceful sleepy town; no police, no sounds of fighter jets overhead and no air raid sirens. Most notably, there is no military presence. Life is so normal that the war seems to be fabricated in some Hollywood type studio and put on TV for everyone’s entertainment.

I go down to the lobby and meet a small group of locally-based journalists. We are about 15 in all, representing a patchwork of different media outfits and nationalities. The ministry has arranged transportation in four Toyota Land Cruisers. Outside the temperature is cool, about 10 degrees Celsius. Asmara is 2,400 meters above sea level so cooler temperatures this time of year are normal.

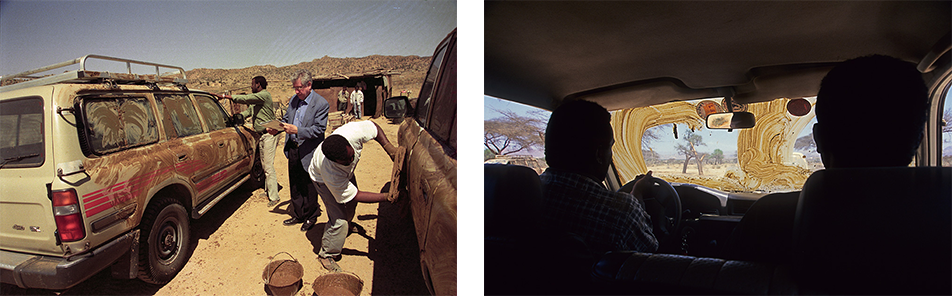

Drivers covering the Land Rovers with mud before the journey to the front. A view from inside the mud-covered vehicle.

It doesn’t take long for the Italian influences and cool air to all but disappear. Outside the capital, the road slowly degenerates to a single lane full of potholes. We continue to wind our way down from the ‘highlands’ blasting the horn at every turn in hopes of alerting oncoming traffic. All of a sudden we stop. The drivers get out and cover the Land Cruisers with mud, from the roof to the wheel hubs. In the end, all that is left are two holes on the front windscreen allowing the drivers to see. This tactic is used to prevent the ‘enemy’ from spotting a sun-glare on the vehicles and thus exposing it to enemy fire. From there on, the trip becomes unbearable. We turn off the main road and continue along a dirt track. Inside the vehicle there is nothing to see except for the mud-covered windows. We drop more than 1,000 meters and the heat inside becomes unbearable. Opening the windows is not a security risk, but rather a health hazard. The dust kicked up by the 4 x 4 in front makes it impossible for those of us trapped inside to breathe. I close my window and pray that our driver will be able maneuver his way up to the front of the pack. That doesn’t happen, so we remain blindfolded in an oven racing over the African savanna.

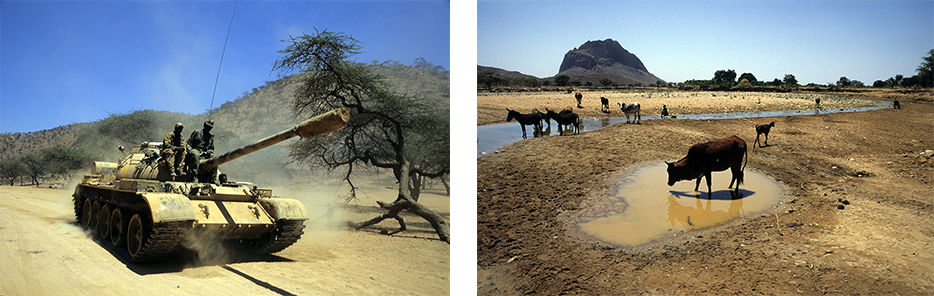

An Eritrean tank makes its way to the battlefront near Tsorona. The Mareb River that flows from the Eritrean highlands to the Tsorona plains also acts as a border between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Unexploded missiles from airplanes litter the landscape near the battlefront.

The war zone is officially marked by two soldiers, standing by the side of the road with Kalashnikovs in-hand. The first two vehicles race through the checkpoint paying no attention to the guards, which only infuriates them. We attempt to pass and the guards stop us at gunpoint and the tell us to turn around and go back to the last village to get official permission. Back at the village the permission comes in the form of a soldier who needs a ride to the frontlines.

We catch up with the rest of the group having tea at a small roadside café. It turns out to be the last inhabited place. From here on, the villages we pass are all deserted.

As we near the plains that border Eritrea with Ethiopia, our drivers take separate paths for security reasons. For the first time since turning off the main road, we are able to roll down the windows and look out over the battle theater that is laid out before us. In the distance, columns of smoke can be seen rising into the sky, marking the spots where tanks or other military vehicles have been destroyed. A small mushroom cloud rises close by, but the sound of the explosion is drowned out by the roar of our engine. After making a few quick turns, which puts us back at the foothills, we see units of the Eritrean armed forces for the first time. The Eritrean soldiers look like a ragtag army dressed in everything from Michael Jackson T-shirts to Rambo-style fatigues. This haphazard way of dressing goes back to their pre-independence guerrilla days when blending in was more important than looking good. Regardless of its soldiers’ dress, the Eritrean army has had a history of operating in small units that are highly efficient, disciplined and mobile. It is also one of the few outfits where women fight alongside men.

Soldiers use water frugally for washing while their comrades gather to bury one of their own who had just been killed.

We stop, get out and start walking up the side of a hill surrounded by army troops positioned on nearby slopes. Artillery shells continue to be heard as we make our way up. The explosions don’t bother the soldiers who seem quite relaxed resting under bushes. Temperatures are now soaring above 40 degrees Celsius. When we reach the hilltop, we see our first prisoners of war. Actually, the POWS tell us that they had deserted the Ethiopian Army and made their way here to seek refuge from this “pointless war.” More shells rain down and an officer instructs us to stay low and make our way down the other side. So down we scramble, more fearful of tripping and breaking an ankle than being hit by a mortar. At the bottom, there is a military camp where soldiers are washing themselves from giant metal drums filled with water. Since water being is scarce, the soldiers use it frugally.

An Ethiopian tank lies crippled in a ravin and an Eritrean tank stands on the battlefront.

Women make up one third of Eritrea’s fighting force.

Not knowing what to do next, I seat myself under a bush to get out of the midday sun. Suddenly, an officer announces that they are taking us to the front. We pile back into the Land Cruisers with a bunch of soldiers and race off over the barren landscape. We stop at the site where a fallen comrade is being buried. From there we are told that we must continue on foot. The commander divides us into small groups of five and we walk in a single file keeping well below the bush cover. Now, the sounds of war are heard from all directions. We walk quickly and quietly behind the group in front. Some of the journalists told me that last time they toured the frontlines they got caught in the crossfire and were lucky to have survived. One of those veterans even brought along a bulletproof vest, but decided against wearing it because of the heat.

We walk for over a kilometer in the direction of the smoke. As we near the battlefront, the sounds of crackling gunfire intensify. In the distance, we see the Eritrean frontline with tanks behind an earthen barrier extending for as far as the eye can see. From where we are, the earthen berm seems to be covered with soldiers sunning themselves. However, as we get closer I quickly realize my mistake.

Eritrean soldiers walk on a protective berm on the front among dead Ethiopian troops killed at close rage.

Dead Ethiopian soldiers

The Eritrean frontline trenches are full of dead Ethiopian soldiers, many with fresh blood oozing from their wounds. According to the Eritrean military, this latest battle had lasted for three days. The Ethiopians underestimated the strength of the Eritrean lines and were repelled. It seemed that all the Ethiopians died at close range.

Over the course of 45 minutes, our hosts hustle us along the trenches to view the carnage bestowed on the Ethiopian attackers. Beyond the Eritrean defenses, the ground is scorched and littered with charred tanks and more dead bodies. We are warned not to venture into this no-man’s-land, as the area is full of anti-tank mines. Knowing that our time is limited, I continue to take pictures while following the guide. Suddenly, through my lens, I see a man staggering towards me from the minefield. I continue snapping away as he walks closer. The soldier appears in a state of shock; he’s covered in grease, dirt and dried blood. Just before he reaches our group he collapses into the dirt face down. A couple of Eritrean soldiers race over and pick him up and an officer asks him a few questions before instructing one of the soldiers to give him some water. After being questioned he is led away. I later learn that he was an Ethiopian soldier who had been hiding beneath a destroyed tank for the past eight hours. He only decided it was safe to come out when he saw that our group was mostly made up of foreigners.

An Ethiopian soldier is taken prisoner after emerging from hiding beneath a destroyed tank. He is given water after collapsing.

The carnage I see during my short stay at the front is indescribable. The dead far outnumber the living. It reminded me of when I covered the Iran- Iraq War where an estimated one million people died in the course of eight years. Similar to the Persian Gulf war, this East African conflict has no regard for the dead. It doesn’t make a difference whether the fallen soldier has identification or not; the names of the deceased are rarely recorded and when the bodies begin to smell they are covered in disinfectant and dumped into a mass grave. Back home, the family is lucky to receive a letter from the government announcing that their child had died a brave soldier defending his homeland.

Luna Bar, the last inhabited place near the frontlines, has no running water or electricity, but surprisingly has cold beer.

Fearful of an imminent counter-attack, our hosts decide to cut our time short and hurry us out of the area. After retracing our footpath, we are loaded back into the Land Cruisers and then race back over the same barren landscape we had journeyed over only a few hours before, until we reach the first inhabited village. There, at the same little café in the middle of nowhere with no running water or electricity, we stop. A waiter comes up and asks what we want to drink. Still dazed from the sights and sounds of the frontlines, I look up and mumble “beer.” Then realizing how ridiculous my request is, I ask for a tea instead. Moments later the waiter returns with a cup of tea in one hand and a beer in the other. I reach out to grab the beer, which to my disbelief is deliciously cold.

I would love to see more of you’re picture, I would love to read more about this my two cousins served in the war both came back I am an ethiopian and although we managed to win the war it was at a bad cost . Both sides lost too much and I feel the blood of the people that died 20 something years ago is still fresh and a new war is coming soon I fear that I would be taken to defend ethiopia. I will proudly but I do not know at what cost