Photographs and Text by Norbert Schiller

In the mid 1990s I was hired to illustrate a book showcasing the splendor of Egypt. As there had already been numerous books published on the subject, I needed to find a fresh angle that wouldn’t seem like a rehash of previous work. Most photo-driven books on Egypt focused on the pharaonic temples and tombs that dot the Nile Valley, which in reality only makes up eight percent of the country. My idea was to explore the other ninety-two percent which largely consists of desert wilderness with a scattering of oases.

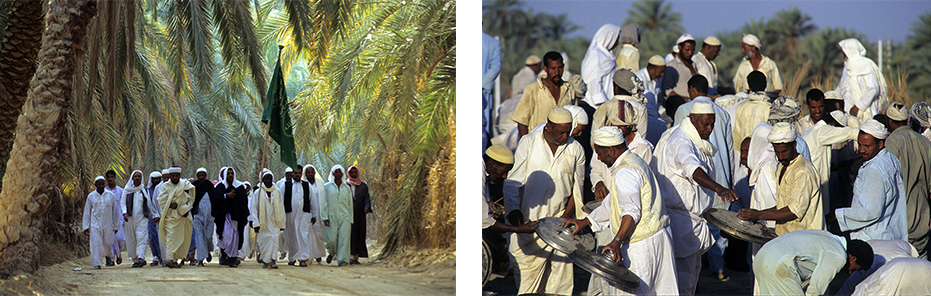

Pilgrims walking to the mulid or religious festival in Siwa. A man on his donkey going through the old town of Shali in Siwa.

The spark that ignited my curiosity about these desert gems was a book by American author Cassandra Vivian titled Islands of the Blest: A guide to the Oases and Western Desert of Egypt. published in 1990. This book would prove to be my greatest source of information on the subject. However, in order to reach the places described in this guidebook, one had to overcome considerable challenges. Up until the late 1990s, GPS devices were banned in Egypt, so desert exploration was off limits for the faint-hearted. There were few paved roads leading to these barren regions and those connecting the oases were in complete disrepair making these verdant spots almost inaccessible. Besides the difficulty of traveling without a GPS, there was limited access to 4X4 off road vehicles. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that car manufacturers, such as Chrysler and Mitsubishi, began producing locally made Jeeps, Pajeros, and other all-terrain vehicles at affordable prices making desert exploration a popular pastime.

My first trip was supposed to be a simple overnight journey to the Ptolemaic settlement of Dimeh es Siba and the Middle Kingdom fort of Qasr el Sagha, on the north shore of lake Qarun near the oasis town of Fayoum, located a few hours’ drive from Cairo. Compared to other off road journeys in Egypt, this one was straightforward and could easily be done in a day. Yet, I chose to spend the night as I wanted to wait for the afternoon light to make my photographs. My friend and fellow photographer Patrick Godeau, who was looking to expand his photo archives on Egypt, accompanied me on this trip as well as most of the other adventures that I undertook while working on the book.

The fort of Qasr el Sagha (L) and the outer wall of the Ptolemaic settlement of Dimeh es Siba at sunset.

Patrick and I arrived at our destination when the sun was low in the sky. After setting up camp near the ruins, we photographed the two sites, and proceeded to have dinner around a large bonfire that we built with wood we had brought with us from Cairo. Then, we blissfully fell asleep under a star-lit sky. Sometime after midnight, we were suddenly awoken by loud yells, and, soon after, we saw a group of men armed with flashlights heading towards us. They turned out to be a police patrol who had spotted our campfire from across the lake and came over by boat to investigate. While they took their time questioning us, the boat that they had taken from the other side of Lake Qarun took off leaving them stranded. As they had no radio to call for help, or blankets to keep them warm, the four police officers resorted to restarting our fire to huddle around the flames. For the remainder of the night, their loud chatter made it impossible for Patrick and I to go back to sleep.

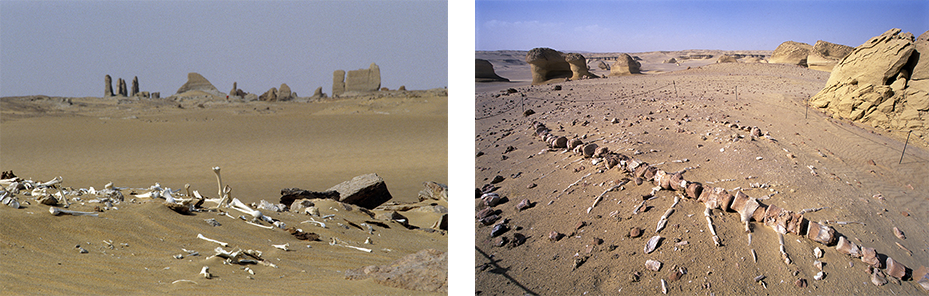

Human bones from Roman tombs lie scattered in the desert around the settlement of Dimeh es Siba. Wadi el Hitan or Valley of the Whales lies west of Lake Qarun and is full of fossilized whale bones that date back millions of years.

At day break, when the officers saw the size of my two-door CJ5 Jeep, their tone changed from boisterous to concerned. It was obvious that there was no way that the six of us were going to fit into this vehicle, which was essentially meant for two, even if Patrick and I were to abandon our camera equipment and camping supplies, which we had no intention of doing. As the policemen sat in a huddle discussing their predicament, the two of us broke down the camp and loaded our belongings into the back of the jeep.

After all our equipment had been packed, I made a spur of the moment decision urging Patrick to hop in as I slammed my foot on the accelerator. As we sped off across the desert, we looked back and saw the police chasing us on foot, yelling at the top of their lungs for us to stop. Fearing that they may decide to shoot at us, I lowered my head below the dashboard and yelled at Patrick to do the same while I sped blindly across the desert until we were out of range. When we got to the main road, I stopped at the first police checkpoint and told them that some of their colleagues were stranded in the desert and needed to be picked up.

The 1993 Jeep Wrangler with its roomy interior beside a rock formation near the oasis of Qara. My compact 1979 CJ5 Jeep on the west coast of the Sinai peninsula.

Before proceeding with our next desert adventure, I had to make some advance planning. As my CJ5 Jeep was old and too small to carry the supplies needed for our future expeditions, I had to find an alternative means of transportation. Therefore, I contacted a car rental agency hoping to make a deal. I convinced them to allow me to use one of their Jeep Wrangler 4X4s for 30 days for the following six months, in return for advertising their business in the book. After I secured the Jeep, I made a similar deal with a tour boat operator which had just began to take tourists on lake Nasser from the High Dam to Abu Simbel and back stopping at remote desert Roman and Pharaonic sites along the way. Lastly, I contacted the Fuji film agent in Cairo to secure the slide film I would need for the coming months.

A fisherman on the North Coast near Marsa Matruh. Camels grazing near a bedouin camp in the desert on the way to Siwa.

On our second trip, Patrick and I decided to visit the remote oasis of Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert to attend and photograph the mulid, a religious festival that takes place every October under the first full moon. Siwa, which lies between the Qattara Depression and the Great Sand Sea near Egypt’s border with Libya, is about 10 hours away from Cairo. As the drive along Egypt’s north coast was quite monotonous, we stopped at a Bedouin camp along the side of the road to break up the journey and take pictures. After being invited for sweet tea and biscuits, we continued to the coastal town of Marsa Matruh, where we turned south and continued on our final four-hour stretch through the desert to Siwa.

The Siwa Oasis with the hilltop fortress town of Shali. The town was built from locally sourced mud and salt between the 12th and 13th centuries AD. In 1926, Shali was abandoned after torrential rains destroyed many of its dwellings.

The people of Siwa are culturally and ethnically closer to the Berbers of North Africa than they are to the Egyptians who live along the Nile Valley. Even though they understand and speak Arabic, Siwans prefer to communicate with each other in a Berber dialect. Up until the mid 1990s, Siwa had remained largely off the tourism grid partly due to government restrictions on foreigners traveling to remote areas of the country. Patrick, who had first visited in 1983 using a special travel permit, immediately noticed the number of Egyptians from the Nile Valley who had settled in the oasis. His first impression was that Shali, the main oasis town, felt and looked more Egyptian. To me, however, it felt like I was in another country.

Pilgrims walk in a procession during the mulid at Siwa. After the celebration, the men join together to clean the pots that were used to feed the guests.

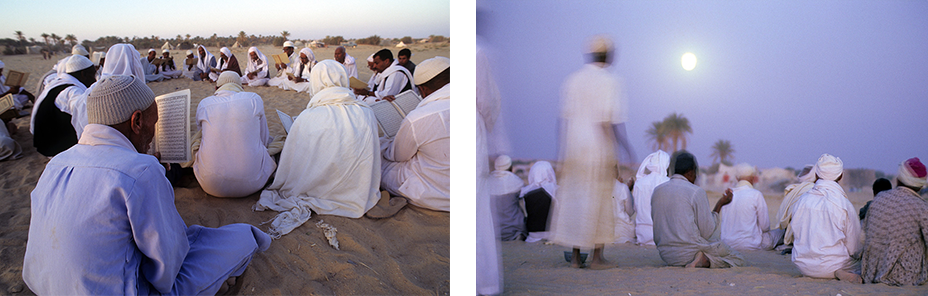

The mulid celebrations in Siwa take place during the first full moon of October.

The mulid is a ritual celebrated by Sufis, who practice a mystical version of Islam. During this celebration, men gather under the rising moon to perform the zikr, or rhythmic chant, while simultaneously moving their body in a circular motion. The celebration can last the entire night. Patrick and I were among a handful of foreigners there as very few people from the outside had heard about the religious festival. During the three-day event, which attracted religious pilgrims from across the border in Libya, we had considerable freedom to move around and take photos as we pleased. Presently, the mulid draws spectators from around the world and tour operators plan visits to coincide with the festivities. Besides photographing the event, we traveled to many of the villages in the oasis documenting the people, architecture, landscape and the annual date harvest, where men climb up palm trees to cut down large bunches of dates, one of Siwa’s prized crops and exports.

Women wearing the traditional Siwa covering. A young man cutting bunches of dates in a palm tree

I had also read in Cassandra Vivian’s guidebook about another much smaller oasis in this region called Qara. The oasis had recently been opened up to foreigners, but visits were only allowed with a special permit. Qara was about a four’s hour drive from Siwa, mostly off road following a dirt track through the desert. Everyone we spoke to suggested we hire a guide, but being somewhat stubborn we decided to make the trip alone. Since it had rained just prior to our departure, much of the dirt track had been covered by shallow pools of water around which we had to negotiate to stay on course. The most surreal experience during the ride was running into a military checkpoint in the middle of nowhere where soldiers asked to see our travel permit before letting us continue on to Qara.

The inhabitants of Qara, a population of a few hundred, are descendants of slaves who once served the people of Siwa. According to local accounts, only a limited number of people were allowed to live in Qara at one time due to the place’s harsh living conditions and lack of water. If a new birth caused the numbers to rise above the acceptable limit, then one of the elderly would have to leave to keep the numbers in check. Today, residents of Qara subsist on harvesting dates and olives, the only two crops that can grow in the area’s saline soil.

This photo shows what remains of the old fortress town of Qara which was destroyed by heavy rains in 1982. This new village was built by the government to house the residents after they were forced to abandon the fortress.

We were warmly welcomed at the village guest house by Sheikh Hassan, the village elder. He told us many stories, namely one about the bombing of the village by the British during WWII, when he was a child, to destroy olive vats which had been mistaken for tanks used to store petrol for the Germans. The sheikh also gave us a grand tour which included visits to a water spring, to most unusual rock formations in the surrounding desert, and to the hilltop mud fortress which had been home to all inhabitants of Qara before it was destroyed by heavy rains in 1982. The residents were then moved to government-built cement houses, but the skeleton of the fortress still towers above the new settlement.

After our tour, Patrick and I proceeded to explore the oasis on our own. The next morning, we woke up at first light and captured unique photographs of farmers on donkey carts passing in front of the old hilltop fortress on their way to the fields. After saying our goodbyes to Sheikh Hassan, we drove back to Siwa carrying with us a special memory of this enchanted and still secluded oasis.

Sheikh Hassan, the village elder, takes us on a tour of the oasis which includes the spring that supplies Qara with water.

For our return trip to Cairo, we decided to take a different route than the one we had taken to get to Siwa. Instead of traveling along the coastal road, we chose to take a recently opened military road that cuts through the heart of the desert to connect Siwa to Bahariya oasis. Besides securing yet another permit, we made sure to carry a few essentials for this grueling 425 km journey such as water, fuel, and spare parts as there was nothing along the way except for a single military checkpoint. In terms of food, Patrick and I tended to travel light, but the two things that we made sure we had in abundance were cigarette cartons and boxes of tea, both of which proved to be more valuable than gold when passing military checkpoints in remote desert areas. At the tiny oasis of Areg, which was uninhabited except for a few soldiers, we ran into one of these checkpoints. After presenting the captain in charge with a carton of smokes and a box of tea, he offered to take us on a side trip to show us some prehistoric cave paintings and tombs dug into the side of a rock cliff.

Ancient tombs dug into the face of a giant rock. A painting inside one of the tombs shows a man and an animal beside a palm tree.

The barren 400 kilometer stretch between the oases of Siwa and Bahariya.

The drive through the desert interior proved to be an exhausting undertaking because the road had only been used by tanks and other military vehicles. The entire way, the Jeep Wrangler bounced about and rattled so much that I feared something would eventually break. Fortunately, we made it to Bahariya safely and took a few days to relax and photograph some of the beautiful sites that the oasis had to offer. It didn’t take me long to realize that Bahariya had characteristics that distinguished it from the other oases. Physically, it is surrounded with barren rock mountains, which are more typical of south Sinai than the Western Desert. Culturally, the main town of Bawiti feels more Egyptian than the other oases. This may be due to the fact that Bahariya falls within the Giza governate which extends from the Nile all the way to the oasis allowing migration of people and goods.

An old mosque in Bahariya’s town of Bawati. The mosque was later torn down and replaced by modern version which does not fit the character of the oasis. A farmer and his donkey returning from the fields.

The drive from Bahariya to Cairo was also about 400 kilometers, but it wasn’t as nerve-racking as the preceding journey. The highway had recently been widened and resurfaced and there were full-service rest stops along the way. The most fascinating feature of this desert stretch are the sand dunes which have been slowly migrating across north Africa for millennia. These soft yellow ocean wave-like dunes, which reflect both light and shadows, were visible for much of the journey.

Back in Cairo, my first concern was to develop the film to make sure that there were no technical glitches that could have affected the events and landscapes I had traveled so far to capture. After I was assured that my images were good, I began planning for our next photographic adventure.

This is fabulous. Thank u so much for sharing. We lived in Egypt for 5 years in the early 80’s. The western desert was just opening up then

It was considered quite dangerous to travel there then. Gotta love Cassandra for her pioneering spirit.

Thank you. So many memories of adventures we had while working in Egypt. Colleagues very generously sharing their favorite sites with us over the years.

Wow, the tomb at Areg is amazing! Would love to see more photos. And the spring at Qara–is it in the new settlement? Where in relation to the old ruin?

Great post, can’t wait for part 2

This is wonderful, I have the work of Vivian The Western Desert of Egypt. It’s a scholarly book, it is making me so keen to visit the deserts, which is how l come across your work. I visited Siwa 4 years ago and l have been researching about the other Oases ever since. I hope i can visit at least some of them, planning to go to Egypt next month