Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

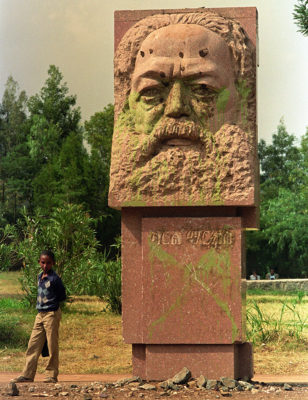

A statue of Karl Marx with mud and paint splatted on his face at the entrance of Addis Ababa University. The statue was a gift from former East Germany to mark the 10th anniversary of the Marxist revolution in Ethiopia.

Following the 1990 collapse of the Soviet Union, repercussions were felt across the world, but especially in Africa. Allies of the communist block were caught off guard when the Iron Curtin crumbled, and they suddenly found themselves deprived of the economic, financial, and military assistance that had helped many of the continent’s despotic regime stay afloat for decades. One of the countries hit hardest was Ethiopia which had been ruled by Haile Meriam Mengistu’s Marxist government for nearly two decades.

Mengistu, who came to power after the 1974 toppling of Emperor Haile Selassie, had been at war with various rebel groups since he took over. He depended on a constant flow of Soviet weaponry and expertise to keep his opponents at bay while, at the same time, keeping the communist dream alive. By March 1991, Mengistu was losing his grip on the country as the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), made up mainly of four rebel groups loosely tied to their respective ethnic clans, converged on the capital Addis Ababa. After successive government military defeats and the halting of aid from the Soviet bloc, Mengistu had no choice but to hand over the reins of power to his vice-president Lieut. Gen. Tesfaye Gebre-Kidan to negotiate with the EPRDF and flee the country fearing for his life.

While Ethiopia was in the final stages of its civil war, I was in Iraq for the Associated Press covering the beginning of the reconstruction phase following the 1990-1991 war. From the day that Saddam Hussein’s forces entered Kuwait on August 2, 1990, my life had been consumed with Iraq and its turmoil. However, now nearly 10 months later a certain degree of normalcy had returned to the country. Bridges, buildings, and other infrastructure that had been destroyed during the conflict was being rebuilt. Additionally, there was a resumption of pre-war activities such as the weekly horse races and the auctions selling everything from rare Persian carpets to everyday bric-a-brac. Although Saddam Hussein had banned the sale of alcohol on the street, as a way to appease the Islamic clergy, nightlife was back in full swing at five-star establishments for those who could afford it.

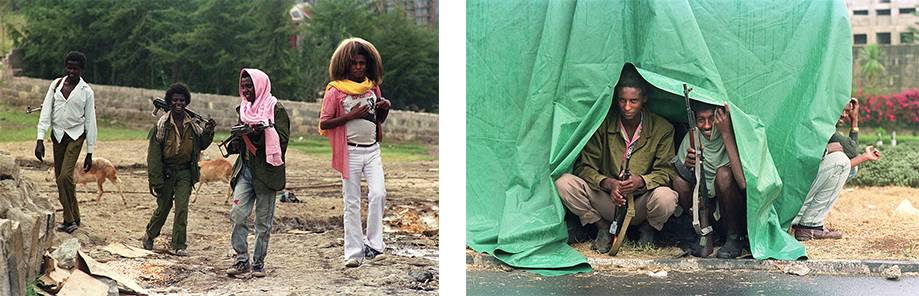

EPRDF rebel soldiers positioning themselves around Addis Ababa after Mengistu fled the country.

One evening in late May, as I was just about to shut down the generator that powered my satellite phone, transmitter, and film scanner, I received a call from one of my editors in London. “We need you in Addis Ababa right now,” he said with of sense of urgency. “What’s happening?” I asked. He explained that Mengistu had fled the country and militia forces were on the outskirts of the capital. “We only have one photographer inside and he’s in desperate need of help.” I immediately packed up all my gear, called a driver to arrange for an early morning pickup, and, after a night’s sleep, made the grueling 17-hour trip to Amman from where I flew back to Cairo. When I got it home, I repacked my bags, replenished my gear, and had a quick dinner with my wife before heading back to the airport for what I thought would be a routine overnight flight to Addis Ababa.

Shortly before we were scheduled to land in the Ethiopian capital, the captain announced that there was no communication with the airport, so he was rerouting the flight to Nairobi. Peter Dejong, a fellow AP photojournalist who was flying in from Amsterdam, had also been rerouted. The first thing we did when we met up at the office in Nairobi was to figure out how best to get to Addis Ababa. Overland was out of the question as in the best of times the 1500 kilometers drive could take anywhere from two to three days, and, considering the situation in the country, we didn’t even know if the road was still open.

Etheopian Orthodox Christians flock to the church during the revolution.

After some deliberation, we decided that our best option was to hire a private airplane from one of the outfitters that normally flew tourists on big game hunting safaris and other expeditions into the Kenyan wilderness. Filling the seats with passengers to help offset our cost was easy because many other journalists were also desperate to get to Ethiopia. After spending two days preparing our departure and buying needed supplies like a portable gasoline-powered generator, bottled water, film and chemicals, we were ready. When we were finally about to depart, the bush pilot who was flying us to Addis Ababa expressed his apprehension about the two-and-a-half-hour flight. He made it very clear that he did not intend to spend a lot of time in Ethiopian airspace, and, if he felt that safety was an issue, he would immediately turn around and fly us back to Kenya. An hour into the flight, we came up against our first obstacle. The transponder at Addis Ababa International Airport had been turned off, so there was no way to determine the exact location of the airport. As we were the middle of the rainy season, the challenge was even greater as the pilot had to fly beneath the clouds to attempt a physical sighting. The other hurdles were the high mountains surrounding the Ethiopian capital and saving enough fuel for the return journey.

When we reached the general vicinity of Addis Ababa, the pilot dove beneath the dense cloud cover to see if he could spot the city or the airport. After circling the area without success, he made a hasty decision to abort the mission and fly back to Nairobi. As we were trying to convince him to make one more pass, someone spotted the runway in the distance from the side window. Before landing, the pilot made a reconnaissance pass to make sure there were no obstacles on the runway. My only memory of that landing was looking out the window and seeing rebel soldiers pointing an anti-aircraft gun at us as the plane touched down on the tarmac.

Except for this group of rebels, the airport was completely deserted. After we disembarked, the pilot, who just wanted to get the hell out of there, was about to taxi to the end of the runway when, all of a sudden, a car came racing down the airstrip. Two members of an international TV crew jumped out and asked the pilot to take some video cassettes back with him to Nairobi. While they were talking, I interrupted and asked if they could give us a ride into town. “No, there is no way you will all fit!” was the answer. At this point Peter intervened saying, “then your film can stay here! We chartered the flight, and we decide what goes on it.”

After a very tense standoff, where the pilot threatened to leave, we came to an agreement. The pilot would take the videos back to Nairobi and we would somehow manage to get everyone into the car, including the equipment, using the roof if needed. I don’t remember the exact number of passengers who crammed into that vehicle, but I conservatively estimate six of us, plus the two television journalists. My recollection of that ride into Addis Ababa was me sitting on the roof of the car cradling the generator plus all my other gear while looking out over the city, hearing gunfire, and watching plumes of smoke rising in the distance. The city was deserted except for some small bands of EPRDF militiamen who paid no attention to us as we drove at a snail’s pace to the Hilton Hotel, which sits on a hill overlooking the city.

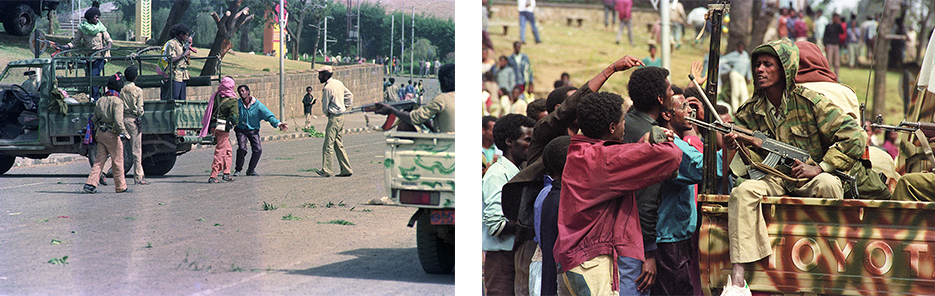

Hundreds of Ethiopians protestors carrying sticks and branches protest against Eritrea’s imminent secession from Ethiopia. EPRDF forces converge on Revolutionary Square rounding up protestors.

When we reached the hotel, we were greeted by Azim, the Kenyan photographer who had been holding down the fort by himself. He was ecstatic to finally have back up and couldn’t stop talking about the events that had been unrolling in the country. It was obvious that he needed a break. Since it was late afternoon, and it was relatively quiet outside, Azim and I decided to take a walk to the center, while Peter set up the equipment. I had visited Addis Ababa ten years earlier while I was a student at the American University in Cairo, and I wanted to get reacquainted with the city. We strolled down the hill to Revolutionary Square, a city landmark that I remembered, but as soon as we reached our destination, we realized that our sight-seeing tour was over. In the distance, we spotted a group of a few hundred protesters armed with branches and sticks heading towards us. They were demonstrating against Eritrea’s attempt to gain independence from Ethiopia, a split that officially happened two years later following a referendum in the breakaway province. When Azim and I began taking photos, the protestors started chasing us. Since we had no chance of outrunning the mob, we fled towards two rebel soldiers standing guard on a street corner. When we reached the two young fighters, one in his early teens and the other a few years older, we pointed frantically to the angry crowd closing in around us. When they were only few meters away, the older of the two teens spit out his cigarette, picked up his walkie talkie, and called for reinforcement. Then his young partner raised his Kalashnikov and opened up with a few bursts of gunfire just above the heads of the crowd. As the protestors were scattering for cover, about a half dozen Toyota Land Cruisers filled with EPRDF soldiers came racing into the square and began rounding up demonstrators. Feeling that we had had enough excitement for the night, Azim and I hightailed it out of there and headed back to the Hilton with pictures to file.

EPRDF soldiers arrest protestors after they marched through the capital demanding that Eritrea remain part of Ethiopia. Some of the demonstrators try to negotiate with the rebels to free the captives.

My two weeks in Ethiopia are now a series of memories in no particular order. Normally, I rely on my films as a reference to help me reconstruct the order of events that I covered. However, for some reason, I never put these particular negatives in dated envelopes, so I have no way of remembering the chronology. Besides my photos of the protest, which occurred on the first day, the only other images that I’m able to date are of the ones of the two massive ammunition depot explosions in the capital.

Two consecutive explosions at a munitions depot rocked Addis Ababa killing and injuring hundreds of people.

In the early hours of June 4th, I was woken by the sound of an explosion that shook the hotel. I jumped out of bed, rushed to the window with my camera and took a series of photographs showing a smoldering fire and smoke rising up into the night sky, off in the distance. Shortly afterwards, my room phone rang, and it was Peter suggesting we get our photo equipment ready and meet in the lobby as soon as possible. While I was getting ready, there was a second much more powerful explosion which caused the suspended ceiling in the bathroom to come crashing down covering me in dust and debris. I rushed to the window again, and this time I saw a massive cloud of smoke blanketing the city. After taking more photos, I grabbed my camera gear and made my way to the lobby to meet my two colleagues. We set out on foot towards the explosion site as there were no taxis on the street due to the curfew. As we rushed towards our destination, we could hear ammunition detonating, and, when we got closer, we saw many dead bodies, some decapitate, of people that ran out of their homes after the first explosion and got caught when the second explosion occurred. The shanty town surrounding the ammunition dump had been completely flattened and was smoldering. Families were digging through the rubble looking for loved ones and the few belongings they could salvage.

An EPRDF soldier walks past the entrance of a military base near the explosion site. An EPRDF soldiers walks past a civilian killed by flying shrapnel from the blast.

The explosions, allegedly caused by sabotage, killed and injured hundreds of people. One of those who were severely wounded was seasoned Kenyan cameramen and photographer, Mohammed Amin, best known for breaking the story of the Ethiopian famine in 1984. He had rushed to the scene shortly after the first explosion and then lost his arm from flying shrapnel in the second blast while his soundman was killed. Amin had to be airlifted back to Nairobi, an operation which required international intervention.

An EPRDF soldier takes cover from flying shrapnel after two explosions rocked Addis Ababa. Firefighter extinguish fires burning out of control in the shanty town near the munitions depot.

In every conflict that I covered, I had some strange encounters and met unusual characters, and this was no exception. On one of my early morning walking tours of the city, I came across Lorenzo, a middle age man using an amateur point and shoot camera to take pictures of dead government soldiers who had been captured and executed by rebel forces. The militias often left the dead soldiers’ bodies in different parts of the city as a warning to those who supported the government. When we started talking, Lorenzo explained that since his business had closed down, he had taken up a hobby of driving around Addis Ababa every morning and photographing every dead body he came across. He invited me to join him, so I hopped into his Land Rover, and we drove through the streets of the capital looking for more bodies. It turned out that he had been born to Italian parents in East Africa where he grew up. After finishing his studies, he got a job in West Africa where he settled and started a family. At some point, Lorenzo ran into trouble because of dubious business dealings and his marriage hit rock bottom, so he picked up and moved back to Ethiopia to begin anew. He eventually married an Ethiopian and started another family. I toured with him for a few mornings, and even attended a party at his house one evening. After I got to know him, he confessed that his second wife had recently picked up and left with the children but didn’t elaborate on the reasons.

The body of a government soldier dumped by the side of the road. Mothers bath their children in the street near where the body was found. EPRDF soldiers often placed grenades with the pin removed on the corpses of government soldiers so nobody will attempt to move them.

Finding a reliable car and driver was one of the challenges of covering the conflict in Addis Ababa. That’s why I had to find alternative modes of transport such as riding with the Italian businessman or even flagging down pickup trucks transporting rebel soldiers. On one such excursion, the militiamen took me to a square in the city center where the bodies of two young men who had just been executed were lying in the street. Besides the gruesomeness of this public execution, there was something odd about the scene that I couldn’t put my finger on. There were a few rebel soldiers lingering nearby, but all the bystanders stood at a considerable distance and just stared at them. When I moved in closer to make some photos, I realized that the rebels had put a few grenades with the pins removed on top of one of the bodies in such a way that if someone attempted to move the body the grenades would detonate. I quickly backed up out of range and continued to make photographs.

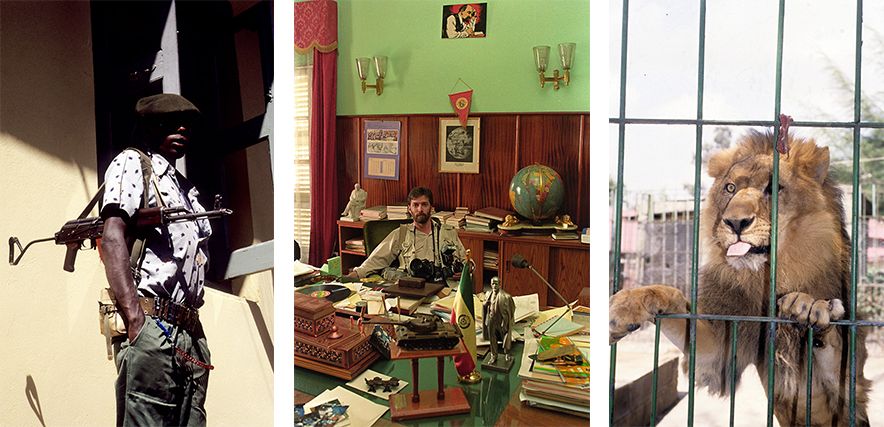

Driving around Addis Ababa in the back of a pickup truck with EPRDF soldiers. A photo of Mengistu Haile Mariam with Fidel Castro and a gold trophy given to former Emperor Hailie Selassie by the Boy Scouts of America are among other memorabilia on a mantle above a fireplace in the deposed president’s office.

The one place that every journalist covering this story visited was the presidential palace. The first thing I noticed as I entered the compound were the lions that Mengistu kept in a cage. Former Emperor Haile Selassie also had lions as pets and had once been pictured feeding his big cats’ large quantities of meat while his people were dying of famine. These images did not go over well at home nor with the international press. I then went in to take a look at Mengistu’s office, which was largely untouched. The first thing I noticed was a photo of him with Fidel Castro and another photo with some school children on a shelf. There were small statues and drawings of both of Lenin and Marx, a small brass soviet tanks, a globe of the world, a small gold colored trophy given to former emperor Halie Selassie by the Boy Scouts of America and a desk full of all sorts of knickknacks. My first instinct was to take a small souvenir, but then I thought that this stuff would better serve the people of Ethiopia if it were one day put into a museum. In the end I only had my picture taken seated behind Mengistu’s desk and as I was about to leave a journalist, whom I’d never met before, asked if I could sneak out a presidential honor guard’s sash in my camera bag for him. He said he’d get in touch with me later at the hotel to get it back, but I never heard from him. To this day the sash hangs in our living room in Beirut and stands as a stark reminder of yet another conflict I covered over my 35-year career as a photojournalist.

An EPRDF soldier inside the presidential compound. Sitting behind the desk of Mengistu Haile Mariam surrounded by Marxist paraphernalia. One of the lions at the presidential compound waiting to be fed.

As the weeks wore on, the EPRDF consolidated its grip on Addis Ababa and a sense of normalcy, however warped, returned to the rest of the country. When the airport reopened, the editors in London decided that it was time for me to leave. As had been the case with so many stories that I had covered, it was hard to detach myself after having experienced such intensity, and I felt melancholic when it was time to say goodbye to my colleagues. Over the years, I started to notice that covering war, and witnessing the worst and sometimes best of humanity, makes it difficult to mentally and emotionally distance oneself when it’s time to move on to another assignment, another story.

Brings back amazing memories of a once in a lifetime experience. It really was the final nail in the coffin of a Soviet African experiment that never should have been. I was there to cover the famine when mengistu left. I’ll never forget us in his office but first had to cross the palace grounds that was covered with burning exploding ammunition and dead soldiers. The explosion at the ammo dump blew out my windows and knocked me onto the floor. We grabbed a car and went straight into the area. Ammunition was exploding everywhere. Guy to my left was hit in the head by shrapnel, took the top of it off. We jumped into a truck to get away and a shell came flying out and blew up in front of the truck. Btw remember Mohamed Amin lost his arm and his sound man was killed just moments before. They were inside the compound when another explosion went off. So many stories of those few days.

Love reading your stories and looking at the awesome photos you took.

Norbert, an incredible story, harrowing yet poignant. Love everything you do.

Hope we can meet up soon my friend.

Brgds

Ken