Text by Norbert Schiller

Photographs by Pam Castens and Norbert Schiller

When I attended the American University in Cairo (AUC) in the early 1980s, it was customary for study abroad students to take a trip during the winter break seeking adventure and new experiences. Some chose to go up the Nile, others crossed into Israel/Palestine, which had recently signed a peace treaty with Egypt, while those who were willing to take more of a risk traveled to Lebanon which was in the midst of a civil war.

My friend Pam and I wanted to go somewhere “exotic,” so we asked our African studies professor Dr. Gail Gerhard for suggestions. “If you want to visit an exotic place on the Arabian Peninsula, go to Yemen, otherwise in Africa go to Ethiopia.” Since we were studying in an Arab country, we decided to experience something different, so we chose Addis Ababa.

A midterm break journey to Ethiopia (L) and Sudan

Neither Pam nor had done any research about Ethiopia before we visited in early 1982. When we went to the embassy for our visas, they neglected to warn us about the areas that were off limits to foreigners. After taking the overnight flight, we arrived in the capital early the next morning. What stuck me first about Addis Ababa was its sharp contrast with Cairo, a metropolis dominated by concrete and constant noise. The airport was surrounded with lush green fields and beautiful trees. While waiting to catch a ride into town at a bus stop across the street from the terminal, I lay down on a small grassy knoll, stared up at the big white bellowing clouds passing overhead, and listened to the chirping of birds. There was no roaring traffic or any evidence of city life, only the sounds of nature. On my most recent visit to Ethiopia in 2018, the greenery at the airport had been replaced with concrete in the form of new and unfinished buildings. The city was buzzing with construction and the once quaint single-story buildings had been replaced with high-rises.

Revolutionary slogans strategically located in and around the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa after the pro-marxist military junta known as the Derg overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.

The journey into Addis Ababa seemed surreal, almost as if we were driving along a country road. It wasn’t until we reached the center that I felt I was in the capital of the second most populous country in Africa. The bus station was chaotic, and we were struggling to find our way to the hotel that had been recommended to us. While we were inspecting our map, a young Ethiopian man came up to us and, in what seemed like a forced American accent, asked if we needed help. Having traveled extensively in developing countries, I was weary of street hustlers, so I brushed him off. After several unsuccessful attempts to get help from other people at the station, I gave up and reluctantly went back to the “hustler,” the only person who spoke English.

Photos I took of the streets of Addis Ababa in 1982 (L) and nearly three decades later, in 2018 when the capital had grown from a provincial city to a modern metropolis.

It turned out Alemu Tadesse had worked for the United States Peace Corps as a translator until 1977 when the program was suspended due to the deteriorating security situation in the country after the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie. For the following four years, Alemu worked odd jobs including serving as a tourist guide but was unemployed when we met him. When we told him about our plans to visit places such as the rock hewn churches of Lalibela or the northern city of Gondar and its historic castles and churches, he informed us that we needed a government travel pass to visit these places. After speaking to Alemu for some time, I got the feeling that he was trying to push his services on us, so I cut the conversation short. As Pam and I were walking away, Alemu pointed to a café/bar nearby and said that he would be hanging out there for the next two days before traveling to his village. “You will never forget me; just remember the Alamo!” he added teasingly.

We managed to find our hotel but, before settling in, we were set on securing travel passes to visit the countryside by ourselves. With help from the hotel staff, we found the tourist office, but they gave us the same information as Alemu. “We can only give you a travel pass if you join an official tour.” The problem with those tours was that they were very expensive, but there was no way other for foreigners to venture outside the capital. With few options left, we decided to go back into town to find Alemu and see how he could help.

The central marketplace in Addis Ababa

When he saw us walk into the café where he was playing billiards, Alemu’s face lit up. He told us there was nothing he could do if we were determined to travel outside Shewa province, where Addis Ababa was located. However, if we were willing to change our plans, we could accompany him to his village of Ambo which was just on western part of Shewa province. To this day when I tell an Ethiopian that I visited Ambo, known for its natural sparkling spring water which is bottled and sent all over the country, I invariably get a warm reaction.

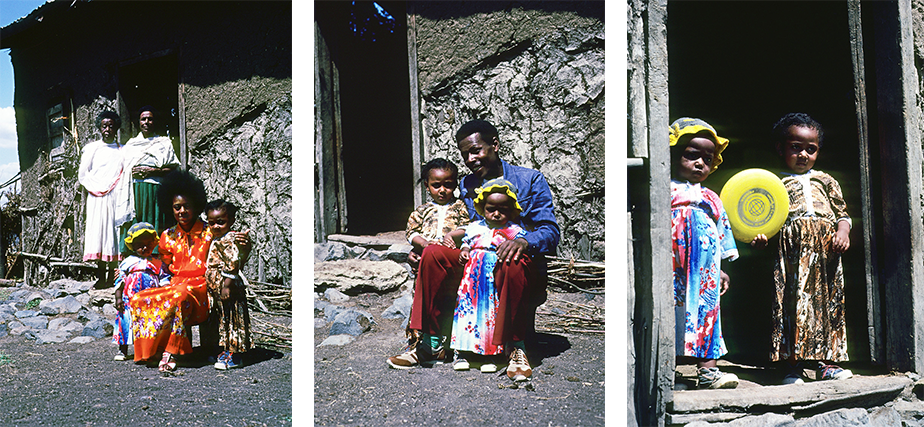

Our local guide Alemu’s family home was made of locally-sourced wood and dung, and covered with a corrugated metal roof. Pam sitting outside the colonial-style hotel in Ambo.

We accepted the invitation, and, the following day, we accompanied Alemu on the three-hour bus ride to Ambo. After we checked into a small, clean, old colonial style hotel and, we toured the village with our host who then invited us to his family home. Like most dwellings in the Ethiopian countryside, the house was made of locally-sourced wood covered in dung for insulation, a dirt floor, and a corrugated tin roof. After meeting with the family, Pam and I went outside to teach Alemu’s two young daughters how to play frisbee. Wherever I traveled I always carried a frisbee with me to break the ice when meeting people for the first time. One of the girls liked the game so much that I relented and gave her my frisbee.

Alemu and members of his family including his mother, wife, and two daughters. One of the two little girls holds my frisbee after she acquired it.

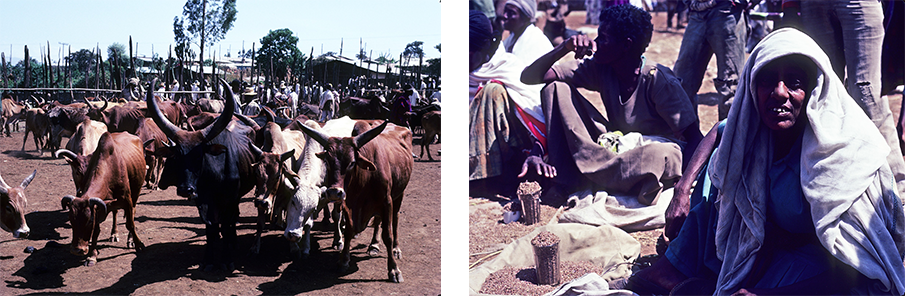

Early the next morning Alemu offered to take us to the weekly animal market where people from the surrounding villages converged with their livestock and other goods to trade and sell. While Pam was shopping, Alemu pulled me aside and asked if I wanted to have baby goat for dinner. Since I had never tasted goat meat, I thought it was a good idea and offered to pay for the animal because I knew that Alemu was going through a tough time financially. However, there was one big problem with our dinner plans. Pam was an animal lover and could not bear to see animals suffer. When we shopped in the Cairo markets, she used to take pity on the rabbits, chickens, and ducks that were kept in cages to be sold as food. To avoid any conflict, Alemu and I came up with a story about offering the animal as a gift to the family so that they could start a small farm to produce dairy products. On the way back to the village, Pam led the goat on a rope and by the time we got to town she had become very attached to the cute little kid.

The weekly animal market where farmers came from the surrounding villages to sell their livestock and other goods.

Later that afternoon, while the family was preparing dinner, Pam and I went on a walking tour of the countryside. The inhabitant of the hamlets that we visited were welcoming and they treated us to Tella, a traditional peasant beer brewed with grain mixed with spices. It didn’t taste like any beer that I was familiar with, and, fortunately, I didn’t drink enough to discover its potency. When we returned to Alemu’s home after sunset, we were greeted with the sight of the baby goat’s severed head staring at us from the center of the family room. Needless to say, Pam had the shock of her life and, as for me, I had a hard time swallowing the bites of raw goat liver mixed with hot pepper that the family members were stuffing into my mouth with the kind intention of thanking me for providing the evening meal. To this day, I have an aversion to Ethiopian food and that was the part that I dreaded most when I went back in 2018 when I was relieved to find that Spaghetti Bolognese had become part of the national cuisine. After a few days in Ambo, we said our goodbyes to Alemu’s family and returned to the capital determined to discover the parts of Ethiopia that lay beyond the Shewa province.

The people and views of the countryside around Ambo

We decided to hop on a bus going east, in the direction of Dire Dawa, to see how far we could get. Somewhere near the town of Awash, nearly four hours from the capital, we were stopped at a military checkpoint and were told to disembark as we did not have the proper permits. I don’t remember the details, but we managed to get a ride to Awash National Park known for its waterfalls, hot springs, palm groves, and amazing fauna. After touring the park with a ranger, we caught a ride back to town and then to Addis as we couldn’t afford the accommodations at the park.

On the way east to Dirwa Dawa, Pam pets a baby goat held up by a local. A twister hits the middle of the highway. The Awash River flows through the heart of the Awash National park.

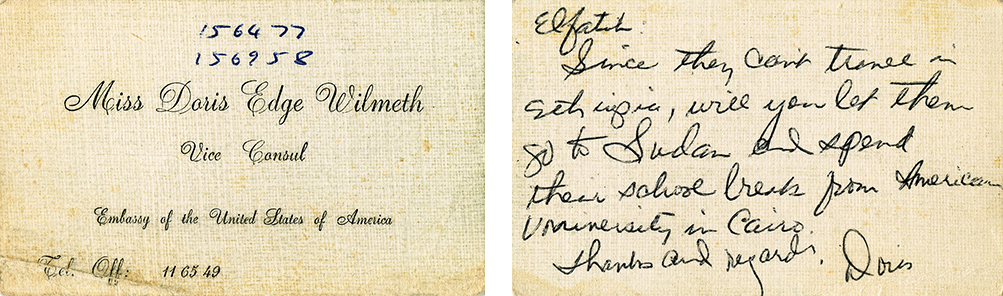

So far, our trip had been a disappointment, except for our time in Ambo with Alemu. With few options left, we decided to turn the US embassy for help. In the early 1980s, two decades before the turning point of 9/11, US citizens still had access to missions abroad, especially in hardship posts, where the staff was surprisingly friendly and helpful. We simply walked into the embassy and asked to meet with a consul. We were then led to the office of Vice Consul Doris Edge Wilmeth who listened to our grievances with great concern and sympathy. She then informed us that the embassy could not facilitate a travel permit, which did not surprise us. However, the VC gave us good advice by suggesting that we abandon Ethiopia all together because of the ongoing civil unrest in the countryside, and that we travel to Sudan instead. She then reached into her drawer, took out a business card, turned it over and wrote a short note on the back before handing it to us. “Go to the Sudanese embassy and give this to el-Fateh. He will sort you out!”

US Vice Consul Doris Edge Wilmeth’s card and her hand-written note to her Sudanese counterpart, El Fatah

Although we had to wait for el-Fatah for some time at the embassy, our time was well invested. The Sudanese official told us that we didn’t need to hire a taxi in Khartoum as the youth hostel was less than a 30-minute walk from the airport. Then he recommended the Sufi celebration in Omdurman on Fridays at dusk and suggested visiting the town of Kassala on the eastern border with Ethiopia as it was one of the most spectacular spots in Sudan. Just as el Fatah finished his briefing, his assistant walked in and handed us our passports with our Sudanese tourist visas.

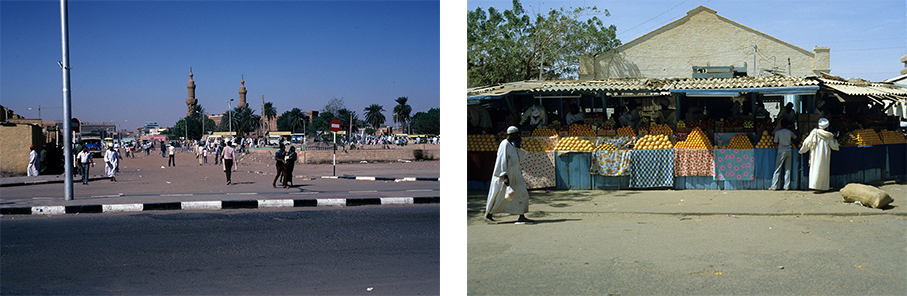

The lack of congestion and open spaces was the first thing that we noticed on arrival in Khartoum.

Khartoum was a relief because it was less congested than Addis and, most importantly, most Sudanese spoke English. After checking into the youth hostel, we went to a small restaurant overlooking Nile where we ordered fish sandwiches and Heiniger beer imported from Germany. A year later, President Jaafar Nimeiri imposed Islamic sharia law banning the sale of all alcohol.

The following day, Friday, we followed el-Fateh’s recommendation and made our way to watch the Sufi ritual of rhythmic dancing and chanting. I have since gone back to watch the Sufis on several occasions, but my first visit will always be the most memorable.

The Sufi procession making its way to the shrine of Hamid el Nil on the outskirts of Omdurman.

Sufis chanting and dancing at the shrine of Hamid el Nil. The man standing to the right of the sheikh wearing the green sash is the brother of Sudanese president Jaafar Nimeiri.

Next we headed to Kassala, once part of an ancient trading route connecting Massawa on the Eritrean coast, with the ancient Sudanese port or Suakin to the north. Taking the bus meant a 10-hour ride with numerous stops along the way. Instead, we chose to hitch a ride on a lorry that crossed a desolate desert track in half the time. After looking out over barren desert for hours, our first glimpse of Kassala was magical. Situated on the banks of the Gash River, Kassala offers astonishing lush scenery with the Taka mountains rising above a fertile plain in the distance. We spent nearly a week in Kassala exploring the countryside on foot and by bicycle.

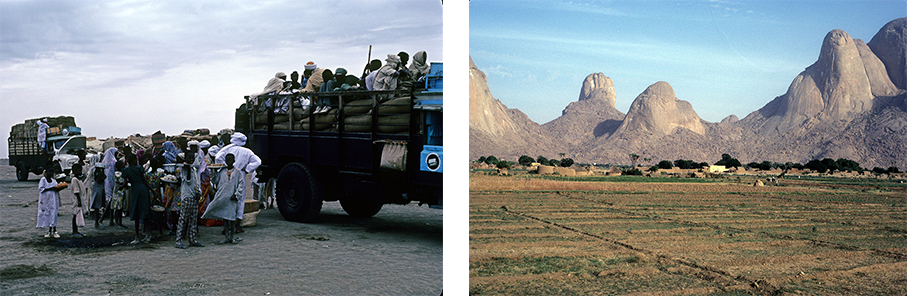

The lorry traveling between Khartoum and Kassala makes a stop so passengers riding on top of the cargo can buy snacks. The Taka mountains rise above the fertile plain near the town of Kassala.

It was during this trip that I discovered the advantages of traveling with a female companion. Everywhere we went, doors opened for us. That’s how we became close to Fatima and her family, who lived at the base of the Taka mountains. Nearly every day, after we finished touring the countryside on our bikes, we would end up at their home. The women felt relaxed enough around me, a foreign male, to dress up in their traditional thobe, a colorful garment, and allow me to photograph them. Marriage seemed to be a priority for the young women in the family and the fact that Pam and I were unmarried and traveling together fascinated them.

Fatima (R) poses with her friends wearing the traditional Sudanese thobe. Pam’s hand decorated with henna. Typical Sudanese tribesmen who lead camel caravans traveling north to Egypt.

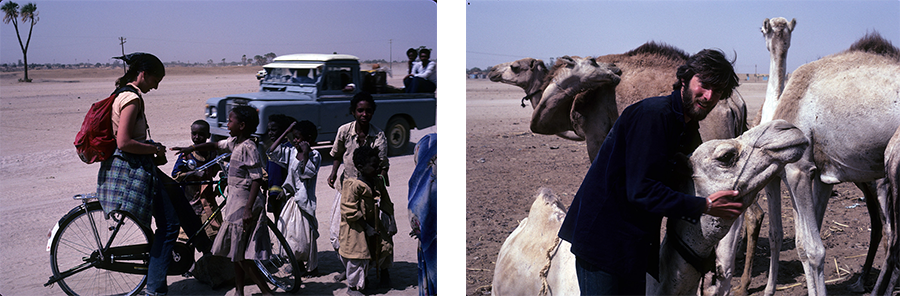

Pam chats with children while exploring Kassala on a bicycle. Getting to know the camels of the region.

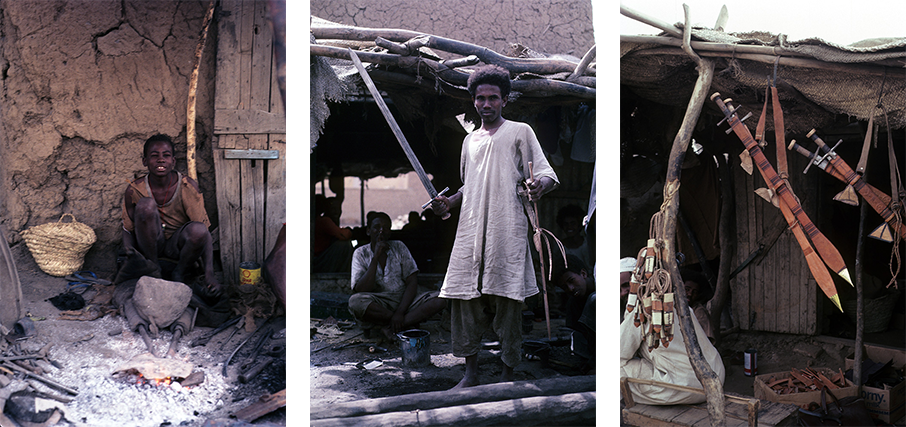

We also spent great deal of time in the souks as I was determined to purchase a traditional Kassala sword worn by the local tribesmen. Instead, I found a beautiful old Ethiopian ceremonial dance sword, which still hangs in our Beirut apartment. In fact, this sword has an anecdote which shows how much the world has changed since this trip. I was able to enter the Khartoum airport and go through security with this weapon in hand without any questions. It wasn’t until I reached the door of the plane that the captain, who happened to step out of the cockpit at that very moment, asked me to hand over the sword until we landed in Cairo.

Metallurgy workshops at the Kassala marketplace where traditional swords are made.

Ultimately, our unplanned trip to Sudan made up for all the troubles and stress we experienced in Ethiopia. When we returned to Cairo, we had many good stories to share with our fellow AUC students. The only adventure, or misadventure that topped ours was that of our roommates Cheryl and Michael who had gone to Beirut. On the way into the city from the airport, their taxi was stopped by militiamen who forced them into their jeep. They were accused of being Israeli spies and interrogated. Since there were photos of PLO leader Yasser Arafat on the walls of the interrogation room, our friends assumed that they had been taken by the mainstream Fatah group. After being held for two nights the couple’s captors ask them if they would like to go the airport or be their guests for a few days. Cheryl and Michael chose the latter and were put up in a hotel and given a tour of Palestinians refugee camps in Beirut. Five months later, on June 6, 1982, the Israeli launched a full on invasion of Lebanon to drive out the PLO.

As with all my early adventures, my trip to Ethiopia and Sudan only strengthened my resolve to live a life which gave me the freedom to travel and discover new places as opposed to being confined to a desk job and an office. Two years after this journey, I chose to become a photojournalist.

Lovely piece. What became of Pam?

Let’s see if she sees this story and maybe she will answer.

She is in Sacramento California. These pictures are wonderful as is the story. I am her sister.