Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

I was on an aircraft carrier in the middle of the Persian Gulf when I first sensed that war with Iraq was imminent. It was February 2003 and I had assignment aboard the USS Constellation which was monitoring the no-fly-zone in southern Iraq. After discussing the situation in the region with the personnel onboard, I concluded that it wasn’t a matter of whether there would be a war, but rather when the war was going to start. A month later, on March 20th, the U.S. and its allies launched what became known as the “shock and awe” bombing campaign of Iraq.

Between May and December 2003, I was sent to Iraq on three occasions to cover the aftermath of the U.S. invasion. Iraq was not a new assignment for me as I had covered the latter stages of the Iran-Iraq war in the late 1980s, and I was in Baghdad during the 1990/91 Gulf War which followed Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Throughout the 1990s I returned to Iraq on numerous occasions to cover the effects of the U.N. sanctions on the country. My last trip, prior to 2003, took place in 1998 and was meant to precede a pilgrimage by Pope John Paul II to Ur, the birthplace of Abraham. Unfortunately, the pontiff’s visit was cancelled due to the deteriorating security situation in southern Iraq, Abraham’s birthplace.

The U.S. military stationed beside two monuments that were symbols of Saddam Hussein’s eight-year war with Iran. The monument to the unknown soldier (L) and the Victory Arch.

Although Iraq was familiar territory, the one thing that was a novelty on this assignment was related to technology. This conflict marked my first coverage of a significant story using a digital camera. About a year before the Iraq War, I had switched from using film to digital cameras and I was not very happy with the results. As a precaution, I brought along my film camera to back up what I was shooting digitally. Thinking back, it was hard labor on my part, but it took me a while to become comfortable with and trust the new technology. Granted, I did not own the most expensive camera on the market because I knew that the camera sensor technology would improve significantly in no time. The news agency that I worked for must have been thinking along the same lines when they equipped me with digital gear that was just good enough to get the job done. After my Iraq War coverage, I rarely went back over my images because I thought they were inferior to my previous work shot on film. As I look back over my archives more carefully now, I have come to realize that I had overreacted.

U.S. soldiers man a road block near the town of Faluja 50 kilometers from Baghdad on the Jordan Baghdad highway. The soldiers are searching automobiles, coming from Jordan, for weapons and explosives.

When I got the call to go to Iraq at the end of April 2003, I had no idea what to expect. After the 17 hours road trip across the desert from the Jordanian capital, Amman, I finally made it to Baghdad, a city so battered that I barely recognized it. Over the previous two decades, I had witnessed the Iraqi capital transform from a vibrant city with crowded shopping districts, bustling bazaars, restaurants, hotels, and nightclubs to a city that was slowly being boarded up due to the crippling United Nations sanctions and the exodus of young, educated Iraqis looking for a better future. I arrived a little over a month after the bombing had begun and the first thing that struck me was the degree of destruction that the capital had suffered. Looters were everywhere removing whatever was left in abandoned and bombed out buildings going as far as stripping the copper wiring from the electrical and communication cables strung up on poles across the capital. Nearly all government buildings had been hit during the air strikes which made them fair game for looting. Not surprisingly, the only ministry left unscathed was the Ministry of Petroleum now under US military protection.

A U.S. military foot patrol catches looters stealing cable from inside Baghdad’s central telephone exchange. The U.S. military patrols areas of Baghdad which were destroyed by the bombing campaign. A month after the war ended looting in the capital continues to be a problem.

On previous assignments, I had always stayed at one of the big 5-star hotels in Baghdad. However, on this trip, due to the astronomical costs at those relatively luxurious establishments, I stayed at Kasr el Shark (Oriental Palace), a small hotel off Saddoun street in one of the main shopping areas. With its quaint atmosphere, plentiful bar, intimate dining room, and helpful staff the hotel catered mainly to western aid workers and members of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The only drawback and safety liability, was the huge glass façade designed to offer an unobstructed view of the street from the dining room and lobby area. To protect guests from flying glass caused by explosions or gunfire, the management covered the façade with heavy curtains creating a dark atmosphere which echoed the mood outside.

A group of five Iraqi barbers spend every day, accept Friday, cutting the hair of U.S. military personnel for one dollar inside the reception area of what was once Saddam Hussein’s main residence in Baghdad. Mirrors that previously hung in different parts of the Republican Palace have been brought here to this make-shift barber shop.

The days were long, and the 45-degree heat in May was stifling. The air conditioner did little to cool my room, but its rhythmic rattling was enough to drown out most of the noise coming from the street. Although the power grid had been destroyed during the bombing, the city was powered by private generators which ran constantly. This provided some relief, especially during this hot season, but the diesel spewed by the generators made the air quality toxic. What made the pollution even worse was the smoke caused by burning trash and acts of arson. The latter mainly took place at night, when it was too dangerous to venture out and the only sounds permeated the nights were those of barking dogs and the bursts of automatic gunfire.

Members of the U.S. military’s 2nd Squadron, 2nd Armored Calvary Regiment known as “Fox Troup” help out at a gas distribution center in Sadr City (formally known as Saddam City) on the outskirts of Baghdad. “Fox Troup” base themselves out of what is known as “the Bunker.” Almost nightly “the Bunker” comes under attack by drive-by shootings and rocket propelled grenades. They share “the Bunker” with an Iraqi family (R) who has taken refuge there since the war began.

Every morning our small group of journalists working for the European Press Agency (EPA) gathered at a temporary office near the hotel to go over the day’s schedule. After deciding on the coverage of press conferences and other scheduled events, we would get into our respective chauffeured cars and start the day. The key was to stay attentive in case of unexpected developments as we drove around the city. Those could range from demonstrations by former Iraqi soldiers who had been discharged without pension to foot patrols by US military rounding up looters.

A military foot patrol walking through a commercial district in Baghdad. Soldiers checking out the latest bootleg videos and games. A soldier lets a woman listen in on his radio. Taking an ice cream break.

Occasionally, I would hook up with a US army foot patrol and accompany them through the back streets of Baghdad. Most of the time the tour was uneventful, and the soldiers would spend their time talking with the neighborhood residents or playing games with the pack of kids who seemed to always tag along with the troops. When we ended up in a commercial district the soldiers would check out the latest bootleg movie and video games, pick up souvenirs, and, when they needed to a break, sit at a local establishment to enjoy street food. There were a few occasions where we had to hunker down after hearing gunshots possibly directed at us. During one particular patrol, the unit that I was with found a suspicious item on the street and cordoned off the area until a team equipped with robotic gadgets arrived to dispose of the object in question.

Family members search through thousands of plastic bags containing the remains of mostly Iraqi Shi’te Muslims who were discovered in a mass grave near the village of El Khatonia, 80 kilometers south of Baghdad. All the victims were killed by loyalists close to Saddam Hussein after the 1991 February and March Shi’ite Moslem uprising in the south of Iraq. Besides soldiers who rebelled Saddam’s rule the mass grave contains the remains of women and children.

The first big story I covered, was the uncovering of mass graves outside the village of El Khatonia, 80 kilometers south of Baghdad. These bodies were unearthed over a decade after the 1991 Shiite Moslem revolt that led to the murder of approximately 200,000 people by Saddam Hussein’s henchmen. I witnessed heart-breaking scenes of families going through one plastic bag after another in a desperate attempt to locate the remains of relatives and then shrieking in horror when they recognized something like an I.D. card or clothing of a loved one who had been missing for all these years. The images that I captured on the several occasions that I visited the mass grave site were powerful.

A man discovers a body with a faded photo I.D. card of a female relative who disappeared over a decade ago.

The other significant event that I worked on was the ransacking of Baghdad’s national museum during the US invasion. Between April 9 and 13, the security situation near the national museum had deteriorated so badly that the staff were forced to leave. A few days later, the museum was overtaken by looters who stole thousands of ancient archeological treasures. When I was there in May, members of the U.S. military were working with local staff to assess the extent of the damage and record the missing pieces as well as those that were still there. The team’s mission was to disseminate the photos and details about the stolen artifacts to police networks across the world to track them down and hopefully repatriate them. Twenty years after the conflict, thousands of items have been returned but many valuable pieces remain in the hands of private collectors showing up every now and then at auctions around the world.

Captain Dave Wachsmuth, from the U.S. army and Thuraya Al-Bazzaz, the Public Relations Manager for Antiquities and Heritage at the Iraqi National Museum in Baghdad look over some of the recently returned artifacts that were stolen from the museum. A combined task force of 14 U.S. customs officials and U.S. military personal are working together to help and recover looted item from the museum. A mural of Saddam Hussein looking over the Tigris and Euphrates River remains intact inside the museum.

Without a doubt the most iconic image of the 2003 invasion of Iraq was the toppling of the Saddam Hussein’s statue on Firdos square. Many photographers were present to capture the moment, but the incident remains controversial because U.S. soldiers were said to be responsible for galvanizing the crowd to bring down the statue. Regardless, the photos and videos showing Saddam Hussein’s statue tumbling to the ground will forever be the symbol of the 2003 war in Iraq.

A man sits atop the statue of former president Ahmed Hassen el-Bakr and hits the head with his shoe. Hundreds of mostly Iraqi Shi’ite Moslems see Bakr as the last visible sign of the Baathist and gather to tear down the president’s statue. Bakr was president of Iraq from 1968 to 1979 and was responsible for bringing Saddam Hussein to power. The sign reads “SADDAM BROUGHT DEATH TO IRAQ AND ITS BANDS DESTROYED IT”

I had my own experience with statue toppling in Iraq, but it wasn’t as spectacular as the one involving the Iraqi leader. On one of my drives through Baghdad, I noticed a crowd throwing stones at a large bronze statue in the center of one of the roundabouts. When a construction crane was brough to the scene, I realized that the intention was to knock down the statue, so I quickly got out of the car and began taking photos. It turned out that the statue was of Ahmed Hassen el Bakr, Saddam Hussein’s predecessor whose presidency ended in 1979. To the crowd, mostly Shi’ite Moslems, el Bakr’s statue was the last standing symbol of the Baathists and had to be taken down. Even though the images I took were strong, they were a footnote compared to those that captured the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue.

The statue of former president Ahmed Hassen el-Bakr comes crashing down with the help of a crane.

One of my main assignments, was to cover Paul Bremer, George W. Bush’s special envoy to Iraq. Bremer’s mission was to oversee the country’s transition from U.S. military rule to Iraqi civilian rule. Unfortunately, the US envoy was ill-prepared for the huge task assigned to him and his mandate was one big blunder. Over the course of a week, in May 2003, Bremer fired any official who had previously been a member of the Baath Party (which meant nearly everyone) then disbanded the Iraqi army. Shortly thereafter, there were hundreds of thousands of unemployed and angry former soldiers on the streets who joined forces with the dejected Baathists to establish insurgency groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria or ISIS.

Ambassador Paul Bremer arrives at a football match between the Police Club and Al-Krath Club as part of a program to distribute footballs to sporting clubs all over Iraq. Bremer also shows off his ball handling skills.

Bremer’s main objective was to make life in Baghdad seem as normal as possible, but his arrogance and ignorance of the Iraqi culture were a great impediment to his mission. I once accompanied him to a soccer match between two local clubs. After meeting with the two teams and handing out soccer balls, Bremer went on to show his ball handling skills by taking shots at the goal and then playing goalie. Finally, when the game began, Bremer sat with some officials to watch, but he didn’t stay long, and, on his way out, he and his entourage walked right through the pitch interrupting the game. There was a very awkward moment when the players didn’t know what to do. It was this kind of arrogance that I would witness repeatedly, particularly by the Americans, during my time in Iraq.

A security guard holding a Kalashnikov stands at the entrance of Kadamein Mosque in Baghdad as Shi’ite Moslems enter for Friday prayers. Kadamein Mosque is the largest Shi’ite mosque in the Baghdad area and since the over-throw of Saddam Hussein thousands of Shi’ite have been attending the Friday prayers.

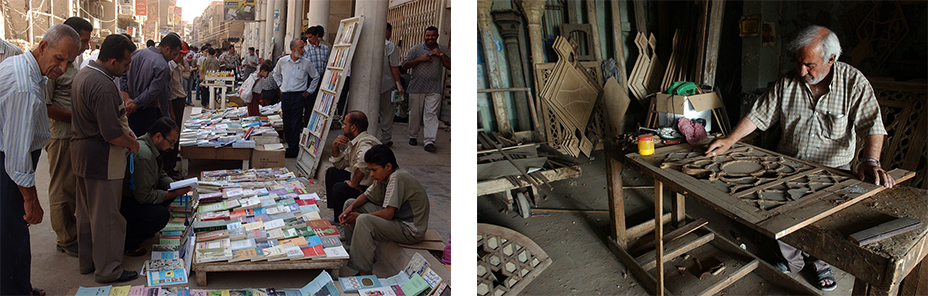

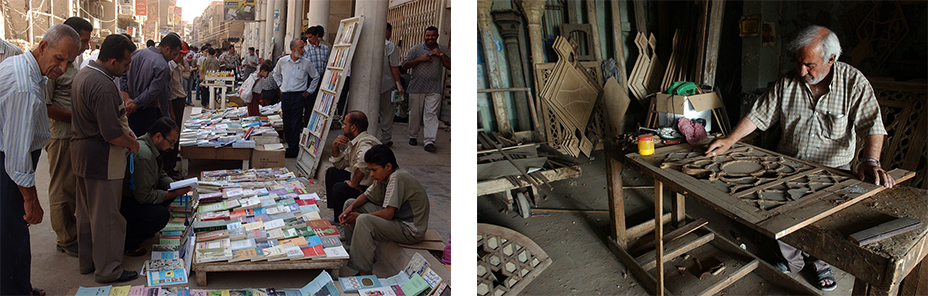

Besides covering breaking news events, I also worked on feature stories that showed daily life. Some of the more colorful features were the weekly prayers at both the Sunni and Shi’ite mosques and the popular marketplaces including the Souk el Nahas or Brass Market where artisans continued to produced artifacts for an almost nonexistent tourist market. I was particularly drawn to the weekly book market where intellectuals and collectors of antiquarian books gathered to discuss literature and rare finds. While searching through stacks of vintage books I was able to procure a few gems myself.

Books sellers and buyers gather at the Friday book market in Baghdad. An artisan makes a window pane at his workshop.

After a month it was time for me to be replaced. Although the situation in Iraq was already on edge during my visit, I felt that the worst was yet to come. Two months later when I went back to Baghdad, the city was in the grip of an insurgency taking a toll on both the local population and the occupying forces.