Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

The dean of journalists in the Middle East, Volkhard Windfuhr, passed away on 19 October, 2020 at the age of 83 in Cairo, Egypt. For 37 years he was the Middle East Correspondent for Der Spiegel magazine and for over a decade he was head of the Cairo Foreign Press Association (FPA). Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, I had the privilege of working with Volkhard as Der Spiegel’s photographer in the region. Together, we traveled throughout the Middle East and far beyond interviewing presidents and kings and covering the conflicts that have wreaked havoc on the region for decades. Our assignments took us as far as Tblisi, Georgia, in the Caucasus, where we interviewed President Eduard Shevardnadze as well as to the Eritrea-Ethiopia border war, one of East Africa’s most contested battlefronts.

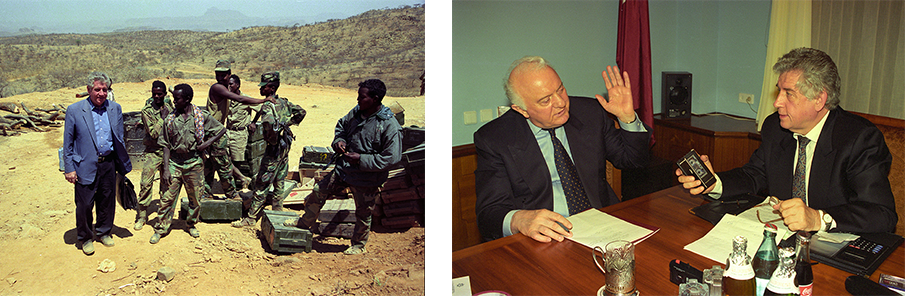

Volkhard carries his signature briefcase while touring the Eritrean front lines during the border war with Ethiopia, March 1999. Volkhard interviews Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze in Tbilisi, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Volkhard was born in 1937, in the city of Essen located in western Germany’s Ruhr valley. At the beginning of WWII, his father was drafted into the German military and died during the conflict. Like most of Germany’s civilian population, Volkard’s family was left destitute by the war. Desperate for work, Volkhard’s mother moved in 1955 with her two sons to Egypt where she found work as a teacher at the German School in Cairo. Volkhard, who had already learned Turkish in Germany, picked up Arabic in no time. After finishing high school at the Deutche Schule, he enrolled in Ain Shams University in Cairo where he studied oriental languages, with an emphasis on Arabic.

Volkhard began his journalism career as a German presenter and translator for Radio Cairo. Gamal Abdel Nasser was president of Egypt at the time, and it was only natural for a young and impressionable Volkhard to get caught up in the Nasser’s pan-Arab movement which was spreading like wildfire throughout the Middle East and further afield. It was during this period of his life that Volkhard made most of his lifelong friendships with some of Egypt’s most prominent intellectuals, writers and artists.

Volkhard interviews Naguib Mafouz (L) at his home in Cairo, 1996. Mafouz was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988. Volkhard speaks to Koranic scholar Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd shortly before he was forced into exile, 1995. Due to Abu Zayd’s critical views on Islamic teachings, he was declared an apostate by a Sharia court which attempted to nullify his marriage to his wife as a Moslem woman cannot be married to a non-Moslem man.

In 1967 Volkhard moved to Beirut where he became a research fellow at the Orient Institute. In 1970, he accepted a position as editor for Arabic programing at Deutsche Welle in Bonn Germany, but moved back to Beirut four years later as Der Spiegel’s Middle East correspondent. After he was abducted in Beirut in 1976, at the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War, Volkhard was transferred to Cairo where he remained the magazine’s Middle East correspondent until 2011.

Volkhard was unlike all the journalists I had ever worked with. He had a genuine desire to connect with the places and people that he covered in his reporting that went beyond news gathering and writing for his audience. Wherever he traveled, Volkhard would always engage strangers in conversations to enhance his own understanding of cultural nuances that would have seemed to insignificant for an outsider. What made him truly unique was that he could converse in at least a dozen languages, half of which he spoke fluently. Whether he was speaking to a head of state or a taxi driver he always tried do so in the interviewee’s native tongue. In the Arab world, he would go a step further and switch to the dialect spoken by the person he was addressing.

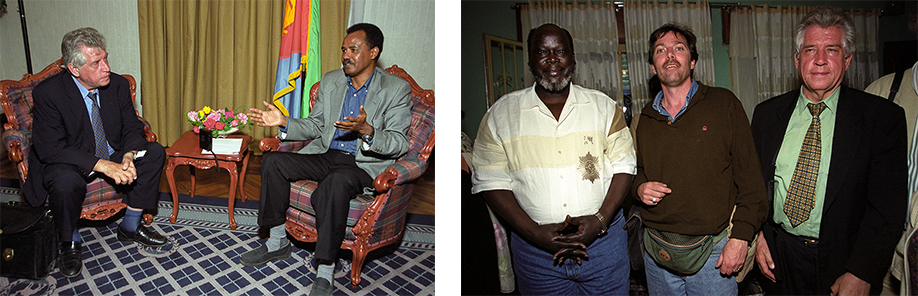

Volkard introduces Ahmed Turabi (L), an influential Islamist scholar in Sudan, to a colleague from Der Spiegel before their interview in Khartoum, 1998. Volkard and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat embrace in Gaza. Volkhard had numerous interviews with Arafat over his career.

On one of our trips to Eritrea, Volhard picked up a book on the Tigrinya language which is spoken in parts of Ethiopia and Eritrea. A few months later we returned to Eritrea to interview the president, Isaias Afwerki. Volkhard began the interview in Tigrinya and then switched to Arabic, Afwerki’s second language. After we were done, I asked Volkhard where he had learned Tigrinya and he reminded me of the book he had bought on our previous visit. He explained that since Tigrinya was a Semitic language with roots similar to Arabic, it was easy for him create sentences once he had learned some of the vocabulary.

Volkhard speaks to Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki, November 1999. Volkhard and I stand next to South Sudanese rebel leader John Garang in Eritrea in 1999, a few years before Garang died in a helicopter crash.

Besides languages, Volkhard’s other great attribute as a journalist was his ability to open doors at the highest levels of government. I have never met anyone who has interviewed more heads of states than him. Shortly after the 1978 – 1979 Iranian Revolution, Volkhard was one of the very first journalists to interview the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini. He also accompanied Anwar Sadat on his historic 1977 visit to Israel, as the first Arab leader to visit the Jewish state in an official capacity. And when PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat flew to Washington DC to sign the Oslo Accords, a peace treaty between Palestine and Israel, Volhard was also on the plane carrying the Palestinian leader from Tunis. As Der Spiegel’s photographer throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, I accompanied Volkhard on many of his later interviews. One day we could be interviewing Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak, at his vacation home on Egypt’s north coast, and a few days later flying to Jordan to interview King Abdullah. More times than I can count, I would receive a call in the middle of the night that would go something like this. “Norbert, get your cameras ready and meet me downstairs in 20 minutes. We have an interview with Arafat in the morning.” Next thing I know, we would be making the 6-hour drive across the Sinai Peninsula in the middle of the night to Gaza City.

Volkhard interviews Jordan’s King Abdullah in Amman, 2002. Volkard speaks to Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, 1997. Volkhard, who had very good relations with the Egyptian presidency, interviewed Mubarak on numerous occasions.

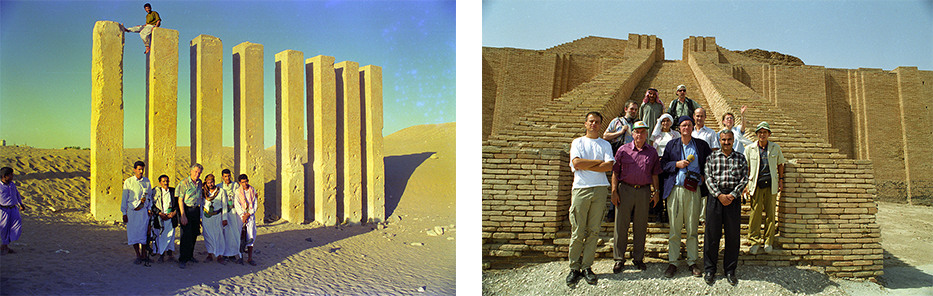

Volkhard’s other passion beside geopolitics, history and languages was the railroads and there was nothing that could stop him when he wanted to pursue anything related to trains. Since head of the Cairo Foreign Press Association, Volkhard organized trips both within Egypt and around the region. One of the more popular destinations for the FPA was Syria, as it was easier to get visas for a press group than for individual journalists. On one of these trips, Volkhard had planned an extensive 4-day itinerary which included interviews with top officials in Damascus, a tour of the Golan heights along the Israeli border, and finally a visit of Syria’s second largest city Aleppo in the northern part of the country. Everything was going as planned when all of a sudden, as we were about to leave Aleppo, Volkhard announced that we are going to make a slight detour to the town of Qamishli in the northeast of the country near the Turkish and Iraqi borders. Nobody in our group had ever been to Qamishli or even heard of it. During the nearly 8-hour bus ride from Aleppo, I pressed Volkhard to tell us the reason for the last minute digression, but he just smiled and said, “It’s a surprise, so keep your cameras ready.”

Volkhard poses with a guide and members of our security during an FPA trip to the Queen of Sheba temple near Mar’ib, Yemen, 1996. Volkhard and an FPA group are pictured at Zagarit, near the ancient city of Ur in southern Iraq, 1998.

Volkhard’s ulterior motives became apparent as soon as we arrived at a derelict train station on the outskirts of Qamishli. The rest of the group didn’t question the reason for adding this obscure town to our itinirary, as they were relieved to finally get off the bus and stretch their legs. Volkhard, on the other hand, was like a child in a candy store running around and climbing the different train engines and railroad cars that were scattered around this forgotten outpost. Although I was delighted for him, I was also apprehensive about the others’ reaction when they realized that the 8 hours spent on a bus criss crossing Syria were only to satisfy Volkhard’s interest in trains. But shrewd Volkhard had already given some thought to some possible criticism. Therefore, as we gathered to board the bus, he announced that we were going to visit one of the last remaining Jewish families living in Syria followed by a meeting with a priest at his parish “to get an insight into the life of the small Christian community that still survives here.”

Volkard meets with Iraqi Foreign Minister Tarik Aziz in Baghdad, 1998. Volkard and a colleague from Der Spiegel speak with the father of Mohamed Atta, the lead hijacker and the only Egyptian involved in the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States.

Volkhard’s obsession with the railroads sometimes got us into trouble. After our interview with Heydar Aliyev, the president of Azerbaijan, Volkhard wanted to visit the main train station in Baku. We took a cab from the presidency, and, as we were walking around the train station, Volkhard became very excited and said, “I have a great idea for a story so start taking pictures.” In the mid 1990s, Azerbaijan, which had recently gained independence from the Soviet Union, was still a police state which was just coming to terms with its newly acquired freedom. I was very reluctant to take out my camera knowing full well that train stations were still considered sensitive military sites. However, because of Volkhard’s persistence, I started taking pictures and immediately a group of plainclothes police surrounded us grabbing my shoulder and escorting us away. Volkhard was beside himself attempting to explain in one language after another, none of which the security officers understood, that we had just interviewed the president and had permission to take photographs.

Volkhard shakes hands with the leader of Qatar, Mohamed Bin Khalifa al Thani, 2009. Volkhard and German Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel present Yasser Arafat with a signed book by Nobel laureate Nagib Mafouz, the late 1990s.

We were led to a room inside the railroad station and there told to sit down. As we were waiting, there was a loud commotion outside, and our guards rushed out to see what was happening. At this very moment, Volkhard turned to me and said “Quick, follow me.” At the back of the room was a second door which opened onto a main street. We ran outside, flagged down a taxi and rushed back to our hotel. That night we were invited to a small party with a few foreign journalists based in Baku. As soon as Volkhard and I arrived we were met at the door by a young Dutch journalist who said, “Ah ha, so you two must be the ones the police are looking for!” Both Volkhard and I looked at him innocently as if nothing had happened. He then explained that earlier in the day he got a call from state security to be on the lookout for two foreigners matching our description. After nodding his approval, he said, “next time I suggest you change clothes before going out again.” The next morning, we hired a car with a driver and hightailed it out of Baku in the direction of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia.

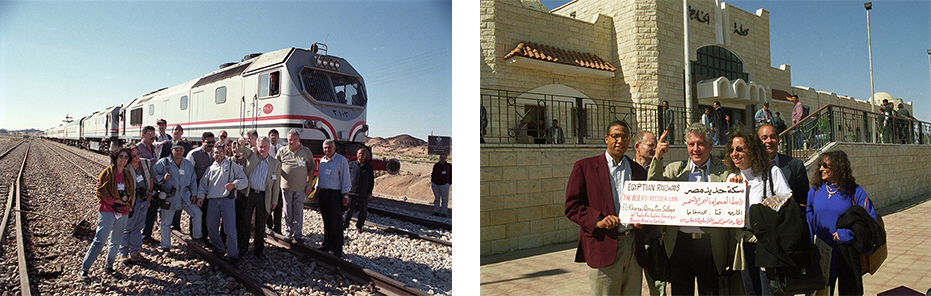

Volkhard leads a joint FPA/FREA trip on a recently restored portion of track between Ginda and Massawa which had been damaged during the civil war in Eritrea, 1999. Volkhard and members of the FPA and FREA are pictured in front of the train in Massawa.

Volkhard’s relationship with the railways didn’t stop with just visiting train stations around the region. For him it meant more. He wanted to single handily revive the regions railways and what better place to start but in Egypt. In the mid 1990s he created an organization called Friends of the Railways of Egypt and the Arab World (FREA) and organized a series train trips. His most popular trip was the Red Sea Desert Link, a 500-kilometer train trip that ran on rails that were normally used to transport phosphate between the Oasis town of Wadi Kharga in the middle of the Western Desert to the Red Sea Port of Safaga. Along with other members of the FPA I joined the first three days inaugural trip that began in Kharaga, continuing on to Luxor and finally ending up in Safaga. Along the way the train stopped at a number of Pharaonic and Roman sites. Volkhard’s vision was to turn this into a luxury tourist train that would eventually be run by an established tourism company. Although this idea had great potential, it never materialized and only catered for a few years to Volkhard and a group of his train enthusiast friends.

Volkhard poses with FPA participants during the inaugural trip of the Red Sea Desert Link, March 1998.

As Volkhard and I crisscrossed the region, discovering local cuisine was never one of our priorities. Sometimes we would be so entrenched in our work that we would forget to eat all together. But there was one specialty that neither of us could turn down and that was a hefty plate of spaghetti bolognaise paired with a bottle of wine. On one of the FPA trips to Eritrea the group wanted to eat dinner at a local restaurant that had been highly recommended. However, neither Volkhard nor I really cared for East African cuisine. I can’t speak for Volkhard’s reasons for his aversion, but for me, it may be due to the scarring memories of raw goat liver mixed with hot peppers I was forced to swallow to avoid offending my hosts when I visited Ethiopia as a student. As our group piled into one taxi after another to go to the restaurant, Volhard and I stayed in the background until everyone had departed. Once everyone was gone, we jumped into a cab and went to our favorite Italian restaurant in Asmara, Castello, and ordered none other than one of the house specialties, spaghetti bolognaise with a bottle of Italian red wine. The next morning, when we were questioned about why we abandoned the group, Volkhard answered with a sheepish grin on his face, “what can I say, our taxi got lost and Norbert and I were forced to eat elsewhere.”

Volkhard celebrates his 25th anniversary with Der Spiegel on a Nile river boat, 1999. Volkhard enjoys a swim in the Red Sea with the late Swiss journalist Janine Kharma near the Eritrean port town of Massawa, 1999.

To me Volkhard was more than a colleague. After all the adventures and misadventures, we shared he became a dear friend. We shared an uncanny passion for exploring new places and collecting postage stamps from the places we visited. To this day the one thing that I inherited from Volkhard was his passion for the railways. Because of him I began walking the derelict railroads tracks of Lebanon documenting with my camera what remains of these routes and diligently comparing them with images taken before Lebanon’s civil war. I had been planning to share my work with Volkhard, but he passed away before I had a chance.

In Volkhard’s memory I will continue my railroad journey and hopefully his spirit will be alongside me for the ride.