Photographs and text by Norbert Schiller

Flood and Wilson, the original “Rough and Tumble,”sitting together on one of two Triumph motorcycles they rode across Africa in 1932.

In late December 1986, I set out to retrace the first ever trans-Africa motorcycle trip with my fellow adventure and water polo teammate, Mark Ehlen. In 1932, Francis Flood and James C. Wilson rode two motorcycles with sidecars from what is now Lagos, Nigeria to the Eritrean port town of Masawa on the Red Sea. Our plan was to begin in Cairo and follow the Nile south all the way to Khartoum where we would turn west and backtrack over Flood and Wilson’s original route.

When we discussed the trip, it seemed doable, but when we put our plan into action it proved to be a logistical nightmare. First, we needed to purchase local motorcycles that were rugged enough to endure the 8,000-kilometers of the most inhospitable terrain in Africa. The Cairo souks provided a quagmire of different bikes ranging from the primitive East German MZ and Czechoslovakian Jawa to the upscale classics such as BSA and Harley Davidson, which were pricy and coveted by deep-pocketed expatriates. The Japanese motorbike revolution had somehow managed to by-pass Egypt.

An entire family in Egypt on a Ural Moto

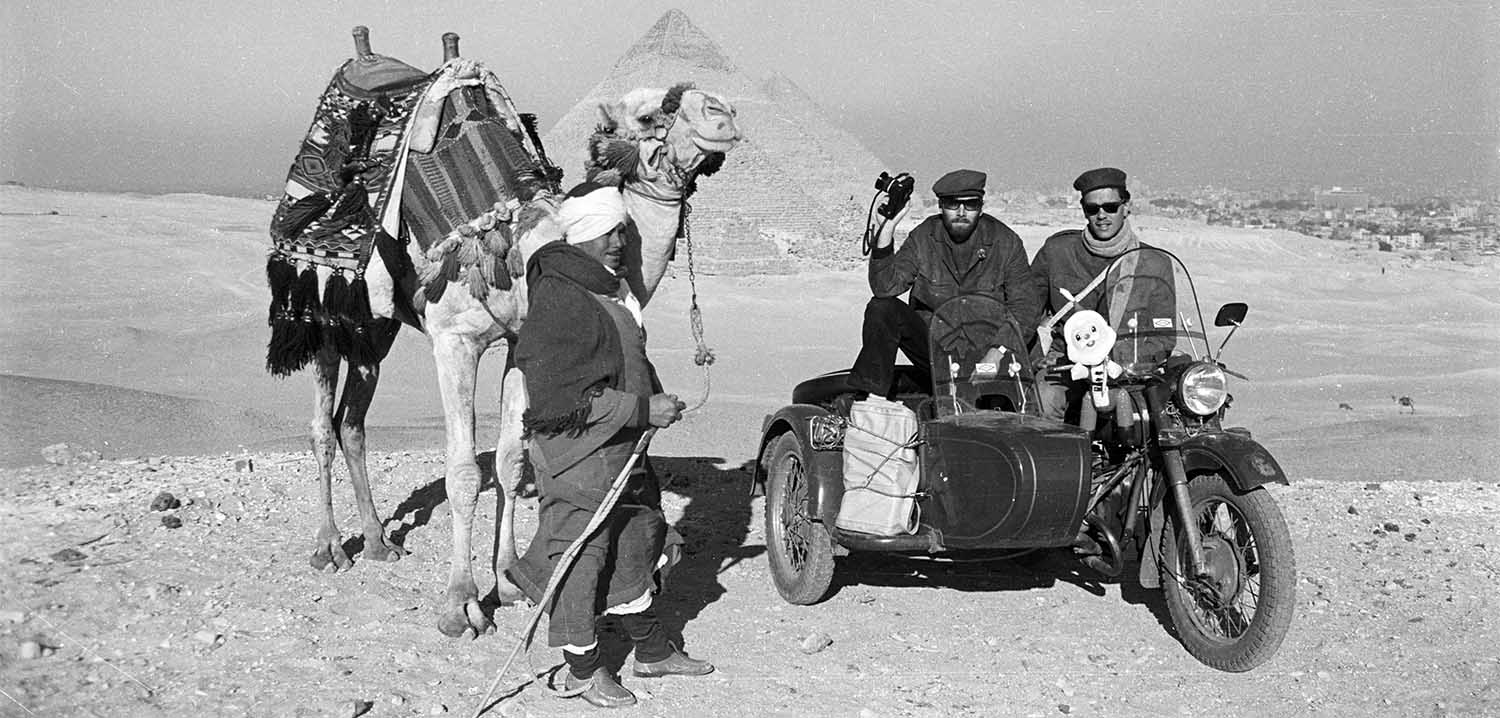

There was one elusive bike on the market that both Mark and I had our eyes on, but were unable to find. It was the workhorse of butchers, flower merchants, and large families that could not afford a car, but were a class above the horse-and-cart crowd. After weeks of searching, we finally found tucked away in one of the many fruit and vegetable markets, the rare piece of Russian muscle we had been looking for – a fire engine-red 1978, 650cc Ural Moto with an optional attached sidecar. As we could only afford one of these bikes, we decided to go with the deluxe version, sidecar and all. Affectionately nicknamed Uri, the bike was destined to take us through the heart of Africa to meet its enigmatic people and discover its still authentic cultures. In conversation, it all sounded so romantic.

After a month of preparing for the trip we departed from Cairo on 26th December 1986. We hadn’t even left the island of Zamalek, in the center of the city, when suddenly the bike began to sputter and come to an abrupt halt in the middle of the road. Amid all the excitement of preparing for our departure, neither Mark nor I had bothered to fill the tank with gas, so here we were, within the first five minutes of our trip, pushing Uri through the streets of Cairo to the nearest gas station.

On the road with Mark behind the wheel and then warming up with some locals by the side of the road.

Sightseeing at the Colossi of Memnon near Luxor and taking a tea, cigarette and shoeshine break by the side of the road.

The road south along the western edge of the Nile, which cuts through fertile fields, was a motorcyclist’s dream. On either side of the road was a patchwork of lush green fields hosting a variety of crops that were divided by a complex maze of water tributaries. Donkeys, sheep, water buffalo and fellahin (farmers) going to and from the fields cluttered the roads running parallel to the Nile. We went from motoring in the cold early morning, through mist-covered farmlands, to driving under the hot mid-day African sun. When we stopped to eat, sleep, or visit a historical site, dozens of people would gather around us, amazed to see two foreigners on what appeared to be a bike from a bygone era. Most were anxious to hear about our journey but once they found out our intended destination they discarded us as two khawagat maganeen, or crazy foreigners, suffering from a serious case of sunstroke!

Our campsite in Aswan. Playing a game on New Years eve to see who can sit the longest on a burning chair.

These early magical moments ended the minute we loaded Uri onto a ferry traveling on lake Nasser between Aswan and the Sudanese boarder town of Wadi Halfa. We had learned that Sudan was suffering from chronic lack of gasoline, so we brought along extra full jerricans to last us a good part of the trip. Unfortunately, because of a fire aboard a ferry a few years earlier that killed over a hundred passengers, the captain of the boat ordered us to empty all the extra jerricans and the bike’s gas tank before boarding. This left us with barely enough fuel to make it from the port to Wadi Hafa. When we reached the town, we were unable to find gas anywhere so we turned to the mayor for help. It turned out that he also was out of gas and needed a ride home. Since we had the only running vehicle in town, we had to oblige and become his private chauffeurs.

Our first photo op after arriving in the Sudan. Stopping at a cafe in the center of Wadi Halfa

After two days, we realized that there was no fuel in this northern outpost and nobody knew when or if more would arrive, so we were forced to abandon the road and pile the bike onto a train heading south. To save money, Mark and I climbed on to the roof of the train where we sat for the next 24 hours admiring the desert landscape as temperatures dropped below freezing at night due to the wind chill, and rose to blistering levels during the day.

Crossing the desert atop a train traveling from the border town of Wadi Halfa to Atbara a total of 24-hours.

When we arrived at the town of Atbara, midway between Wadi Halfa and Khartoum, we climbed down from the train, grabbed our bike, and drove to the nearest hotel where we collapsed for two days. In Atbara, we had better luck. First, we were able to scrounge some petrol from the local police station, and as the day wore on we managed to slowly fill the tank and some of the jerricans by buying gasoline on the black market. By the end of the day, we had enough to continue our journey south.

The most amazing thing about Sudan back then was that there were barely any paved roads. From the roof of the train all we could see were sand tracks leading out into the distant desert. Then all of a sudden, as we began riding south from Atbara, we found ourselves on a newly asphalted road. An open road, with no other vehicles and the wind at out back, what more could one ask for? As those thoughts crossed my mind, a large truck appeared from nowhere and barreled right into us clipping the sidecar and sending us spinning out of control into a pile of gravel by the side of the road.

Tracks leading through the desert. Switching tires in order to get better traction in the sand.

When we recovered from the shock, and straightened out the bike, we realized that the asphalt had come to an end and we were looking ahead at a desert trail. Uri was a heavy road bike built for the roads of the Ural Mountains of the former Soviet Union. The Ural Moto was designed to cope with freezing temperatures and the occasional snowdrift, but not the dry heat of the Sahara Desert and the endless tracks leading through the sand. On numerous occasions, the sand became so deep that the tires sank and the engine overheated and stopped working, emitting a plume of blue smoke. In the middle of nowhere, we had to wait until the engine cooled before we could continue our travels. It was this sort of absurd scenario that started taking its toll on us.

Mark pushing the bike over a train trestle. After a long day Mark hangs upside down in a village well in order to stretch out his back as villagers watch.

Our saving grace was the railroad tracks that stretched between Atbara and Khartoum. If the sand got soft and the going got tough, we would abandon the sand and ride on the elevated ground straddling the three wheels of the motorbike between the metal rails. However, this method too had its limitations as rail trestles that traversed wadis or valleys sometimes proved treacherous to both man and machine. Some rose as high as 9 meters above the wadi, forcing us to stop and manually push the bike over the wood railroad ties one by one. Depending on how long the trestle was, it took considerable time and a great deal of strength. And then there was always the threat of an oncoming train. The alternative, which we resorted to when we were too exhausted to lift the machine, was to circumvent the trestle and wadi all together and travel many kilometers out of our way burning precious fuel and increasing our chance of being stuck once again in the soft sand.

In spite of our grievances, we did meet and stay with an array of interesting characters along the way, including Irish aid workers in a tiny hamlet in the middle of nowhere, and Bedouins ferrying livestock and kitchenware across the desert to make a living. The people we encountered were always kind and helpful, no matter how hostile the environment.

In the evening we often stayed in small hamlets or in bedouin camps.

Once in Khartoum, we rested and reassessed our plans. Since Uri was on its last legs and would not make it any further under such conditions, we decided to abandon our original plan of crossing Africa and chose to ride on the recently paved road to the Red Sea town of Port Sudan from where we would sail back to Egypt on an ocean liner. However, before ending our mission, Mark and I had other plans. We stored Uri at some friends’ house in Khartoum, and I headed off to N’djamena by plane to cover the war between Chad and Libya, while Mark climbed atop another train and traveled around western Sudan. We met in Khartoum two weeks later, packed up Uri, and headed for the coast.

Even though the road was paved the entire 1,200 kilometers to Port Sudan, Uri’s lifespan was coming to an end. Although we had tried to avoid the worst heat of the day by starting our final journey at night, there came a point where the engine just froze and refused to start. Knowing there was nothing more we could do, we just sat on the side of the road and waited to see what fate would bestow upon us. At sunrise, a young Sudanese driving a white pickup truck for the aid group “Save the Children” stopped and offered to help. We piled the bike into the back and rode with him to Port Sudan.

The midlevel Red Sea port town of Suakin which lies mostly in ruins.

Mark and I bought deck class tickets, while Uri was stored somewhere in the cargo hold. During the three-day journey back to Suez via Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, there wasn’t much we could do except read and reflect on the triumphs and defeats of our two-month trip.

It’s been 30 years since Mark and I embarked on our motorcycle adventure.

It’s been 30 years since we embarked on that fateful trip and every time Mark and I get together we reflect on our youthful adventure and dream of attempting it again. The next time, however, we will follow the exact route Flood and Wilson took. Ural Moto has improved drastically since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the new models connect the wheel on the sidecar directly to the drivetrain so that both wheels turn in unison reducing the chances of being bogged down in soft sand. However, there are new challenges of a different nature stemming from new geo-political realities that could prove to be more treacherous than the topography.

What a fantastic story. Egypt in 1986 would have been incredible. It certainly was when I lived there in the 1990s.

Wow. What great memories of tough travels! Between 1986 when you went and the trips I went on in 1991 and ’94, the photos look remarkably similar. Now? Argh, I hate to think…

Thank you for taking the time to put this together. Great stuff!

What a great adventure story Norbert. Thanks for sharing this. Cheers old friend.

Fabulous adventure indeed. Wow!