Forty years ago, I set out with a high school friend to travel around Europe and beyond. This is the third article in a five-part series that will look at my yearlong journey which would eventually determine my life as a photo journalist and adventurer. In this segment, I abandon my plans to travel around the Greek archipelago and make a last minute decision to discover Egypt instead. I made my debut in photography on this trip using an Olympus 35RD rangefinder camera with a fixed 40mm f1.7 lens.

Text and Photographs by Norbert Schiller

After six weeks in the tiny northern Greek village of Agra with the Papadopoulou clan, Steve and I reached the conclusion that it was time to part ways. We had been traveling companions for six months, but the honeymoon was over. Before heading for Athens, on different dates, we decided to split our communal property, so Steve acquired the two-man tent while I appropriated the camping stove.

The Acropolis on a hill overlooking Athens in 1979

On February 13th, I took a nine-hour bus ride to Athens. As soon as I arrived, I checked into the Funny Trumpets, a small hostel popular with young travelers near the city center. After dropping off my bag, I inquired about the cost of ferry tickets to Crete. I became interested in visiting the island after my oldest friend showed me pictures of his backpacking trip there two years before my own journey. He had stayed in a cave on the island and I wanted to do the same. The night before my planned departure to Crete, I was on my bunkbed looking over a map of the island to plan my itinerary, when I became distracted by the noise and laughter coming from the next room. Two American college students, Steve and Hank, were discussing their trip to Egypt with a couple who was also getting ready to leave for Cairo in a few hours. On a whim, I went over to their room and asked if I could join them. “The more the merrier” was the response, so I abandoned my much-anticipated Crete odyssey for a trip that would, unbeknownst to me, change the course of my life.

Cairo greeted us with its traffic and congestion, the city’s welcome ritual.

Steve, Hank, and I arrived in Cairo late on a Friday night, and, while we were waiting for our luggage, a funny little man wearing a bell cap and waiter’s coat came up to us to ask if we needed a hotel. After blowing him off, we stepped out of the airport and suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a swarm of taxi drivers haggling for our business. Luckily, the funny little man, who went by the name of Filfil, or Pepper, reappeared to once again offer his services. We decided that he was definitely the better option, but explained that we were on a tight budget and were looking to take a bus to the city center. Filfil immediately took us under his wing and led the way. We jumped onto bus number 600 that went from the airport to Tahrir Square in the heart of Cairo. During the ride, I got my first glimpse of the city which was abuzz with people, cars, and animals pulling carts. Cairo at midnight was more alive than any other city I had visited in the middle of the day. At that very moment I fell under the Cairo spell.

Hank fast asleep during the 14-hour train journey from Cairo to Luxor

Once we got off at Tahrir Square, Filfil took us to the Golden Hotel which had been recommended to us back in Athens. Unfortunately, the hotel was full, so Filfil suggested we spend the night at the Gershwin, an equally cheap hotel around the corner. The following morning, we went back to the Golden Hotel where the owner, Faris, welcomed us personally. Faris was a kind elderly man who was always eager to help. We later found out that he came from a land-owning Coptic family in Upper Egypt who had lost most of their property and wealth during President Gamal Nasser’s land reforms in the early 1960s. All that remained for Faris was his hotel to which he gave his undivided love and attention. He was sincerely devoted to the patrons, most of whom were young travelers like me, and offered valuable advice on how to experience Egypt on a budget. I grew fond of Faris, and when I moved back to Egypt as a student two years later and then again in 1984 to begin my career as a photo-journalist, I kept in touch and even visited him and his wife at their home in Zamalek.

After two days in Cairo, Steve, Hank, and I took the 14-hour train trip to Luxor traveling in second class. For someone who had only read about Egypt in textbooks, the train ride through Upper Egypt offered an entirely new perspective. This wasn’t the Egypt of the Pharaohs, the Great Pyramids, the royal tombs, and all the past grandeur that tourists tend to see during their fast and furious visits to the country. Here was the beauty and simplicity of the Egyptian countryside, a stretch of farmland on either side of Nile that had been home to the fellaheen, the backbone of this society since the dawn of times.

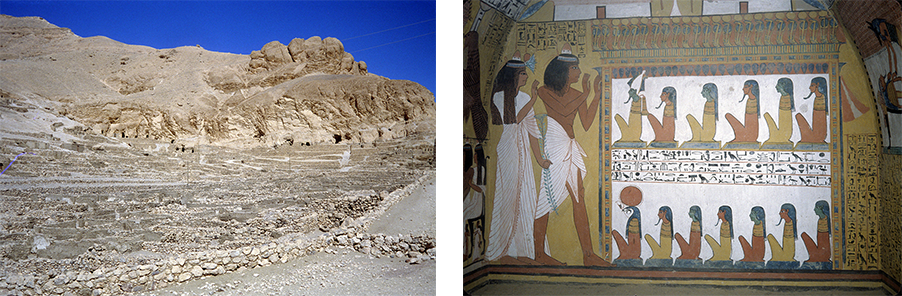

The view of the Valley of the Kings from the hills above. Today the hills surrounding the West Bank are out of bounds for visitors due to security concerns. Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahari was void of tourists when I visited in 1979.

The donkey trail from the Ramesseum with its fallen statue (R) passes between the twin Colossi of Memnon.

In Luxor, visiting the sites was inevitable, but we decided to do it with class, using a means of transportation that was less conspicuous, and cheaper, than a tour bus. We found a local guide named Mohammed who offered to rent us donkeys for 75 piasters (under a dollar) each for the day. Over the course of the next two days, Mohammed and his four-legged assistants took us on a spectacular tour of the West Bank where we visited the historic sites beginning with the Valley of the Kings then continuing over the hills to Deir el Bahari to visit the Hatshepsut Temple. All along, young children followed us by climbing the hill alongside our trail trying to sell tourist souvenirs. Unfortunately, the route between the two sites is no longer accessible due for security reasons. From the Deir el Bahari temple complex, we continued on to Madinat Habu and finished up at the Colossi of Memnon.

The Tombs of the Nobles buried in the cliffs above the West Bank. Most of the tombs were closed when I visited but a small donation or bakhshish to the guard and any tomb could be opened.

The following day, we decided to add a twist to our adventure. Before getting on the donkeys we smoked some hashish, which made for an interesting ride. It also didn’t help that we had much stronger and faster donkeys than the previous day. When Steve tried get off at the entrance of the Valley of the Queens, his donkey bucked sending him flying into the dirt, much to the delight of a group of onlookers. After visiting the Ramesseum and the Tombs of the Nobles, Steve was thrown off again, but this time at full gallop. Somehow, he managed to get up with a smile on his face.

On the third day in Luxor I rented a donkey and explored the villages along the West Bank alone.

Sugercane covers the floor of the train

After two days of exploration on donkey-back, Steve and Hank decided to go back to Athens while I stayed behind to discover more of the West Bank. When I reached the first village, a young boy came up to me and asked if I wanted to rent his donkey for the day. After negotiating the price down to 75 piasters, I set out by myself to discover rural Egypt. Like most donkeys, this one had a mind of its own. Whether I steered right or left, the donkey would invariably head in the opposite direction. In the end, I let the stubborn beast take the lead. In spite of the lack of control over my route and the occasional hassle by locals asking for bakhshish money, my excursion turned out to be a success resulting in the best photographs I had taken on the trip so far.

The next morning, I boarded a train to Aswan. This time, I sat in third class and it was the scene inside the car that was more fascinating that the scenery outside. Here, there were no designated seats or sleeping cabins; people sat on the floor which was covered with trash, and slept in the luggage racks above the seats. When we stopped alongside a freight train carrying sugarcane, there was a mad rush to the windows as riders reached out to grab armfuls of sugarcane stalks. By the time we pulled away, the train car floor was blanketed in sugarcane.

I had heard about a barge that ferried passengers and supplies on Lake Nasser once a week to the Nubian villages surrounding the temple of Abu Simbel. After spending a day in Aswan, I took the train to the High Dam from where the boat was to depart. In fact, there were two barges, one for passengers and one for supplies, both pulled by a single tugboat. The roundtrip normally took three days, but that was when things went as planned. As it turned out, there were other foreigners on the trip, and we all gathered at the top of the passenger barge, while the locals stayed below. On the rooftop, we each took up our respective positions, laid out our sleeping bags, and passed around cigarettes laced with hashish. Just as we had surrendered to relaxation mode, we came to a halt as the tugboat engine broke down, and, for the remainder of the day, we drifted as the captain and crew worked assiduously to get the motor to start up again. Sometime in the middle of the night, they succeeded. However, problems with the engine persisted so the crew tied the two barges up to an island and abandoned us for a day to repair the tugboat. When they returned we resumed our journey south. As we once again fell into a monotonous rhythm, the skies opened up with a downpour causing rejoicing among our Nubian friends as this phenomenon apparently only happened once every two years this far south. We finally made it to Abu Simbel the following day and had just enough time to explore the ruins and buy some snacks before heading back.

A small kiosk sold tea, biscuits and cheese sandwiches to passengers traveling between Aswan and Abu Simbel. All the foreigners slept on the roof of the barge during the journey, while the locals stayed below.

The trip back was supposed to be quicker as we were down to one barge now that we had dropped off the supplies. However, as we discovered on the first leg, nothing ever goes as expected when traveling at the mercy of the elements, in cargo class. On the second day, we were hit by strong winds and big waves, so those of us who had chosen to stay on the roof were told to go down to the lower deck. By late afternoon, the storm got worse forcing us to seek shelter on one of the islands on the lake. While we waited for the wind to calm, some of us went for a swim. Although swimming in the Nile in Cairo was never desirable, even in those days, the water this far south was clean.

Sunrise and sunset on Lake Nasser

Approaching the temple of Abu Simbel. Hanging out with local children who live in villages near Abu Simbel.

After being back on the water for a few hours, we noticed a man in a small fishing boat waving a white flag, a signal of distress. We immediately headed in their direction, and, as we approached, we saw a young boy laying down at the bottom of the boat. It turned out that he had been bitten by a deadly snake near his village and was in serious need of medical attention. We carried the boy onto our barge where one of the travelers from Canada, who happened to be a doctor, spent the next 24 hours trying to lower the boy’s temperature with cold compresses, and draw out the poison using whatever was available on the boat. The boy survived, thanks to the physician’s efforts and a stroke of good luck. We, on the other hand, were not so fortunate as our trip had taken six days, twice the estimated time.

Nubian passengers on the return trip

As soon as I returned to the hostel in Aswan my right leg began to swell and turned beet red. I was in so much pain that I could hardly walk. The next morning, I hobbled over to a German missionary hospital for treatment, but it was Sunday and there was no doctor was on duty. The nurse applied some kind of ointment and told me to come back the following day. Not knowing what else to do, I went back to the hostel to rest. Later that day, a young Egyptian army doctor, who was staying at the hostel on his vacation, heard about my situation from the staff and asked if he could see my leg. I was a bit reluctant to have this young army doctor examine me, and may have even been abrupt with him. Regardless, he proceeded and asked if I was carrying any antibiotics. I still had some tetracycline that I had bought in Italy four months ago to treat an ear infection, so he prescribed two pills every six hours. When I woke up the next morning, both the pain and the swelling had diminished considerably. I immediately went looking for the doctor, who like his Canadian counterpart was chivalrous enough to come to the help of stranger, but I was told that he had already left. It turned out that, while I was helping lift the boy from the boat to the barge, I had stepped barefoot in the blood that had dripped from the wound inflicted around the bite area to drain out the poison. The venom had traveled up my leg through a crack in my foot.

Street life near al Butnya, where hashish and opium were sold.

When I returned to Cairo, the city was buzzing with excitement in anticipation of U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s visit. Carter was the main broker of the Camp David Accords, the peace settlement between Egypt and Israel which was in its final stages. The day before Carter arrived, I set out with two Canadians to discover the city’s underworld. Dave, one of my two companions, took us to an area of Cairo called al Butnya, which was located in the narrow winding alleys between al Azhar mosque, the oldest Islamic university in the world, and the ancient wall that surrounded Cairo. I was not prepared for the bizarre scene that I encountered when we got there. In the middle of the alley were tables loaded with blocks of hashish which were broken off and weighed on scales before being sold off to users who came from all walks of life, including uniformed police officers. Having grown up in the era of the movie “Midnight Express,” which encapsulated the ultimate horror scenario for foreigners arrested for possession, I wasn’t comfortable making a purchase considering the situation. However, Dave assured us that “everyone here is cool.” He then took us to a house with a green door where there were other people already in line. When we finally entered, we were met by a man with a row of silver-caped front teeth who took my two pounds (just over two dollars), bit off a big chunk of hashish, and handed the piece to his assistants who wrapped it in cellophane. After my companions also bought their share, we found a small café nearby where we smoked shishas, or waterpipes, loaded with hashish, drank tea and watched the back streets of Cairo come to life. I later learned that the man with the silver teeth was Mustafa, one of the most powerful hashish and opium dealers in Egypt. The door behind which he sat was known as Bab el Akhdar, or the Green Door. When I returned to Egypt two years later as a student at the American University in Cairo, he was still in business. It was only after Hosni Mubarak became president following the assassination of Sadat in 1981 that al-Butnya was gentrified.

ABC News correspondent Peter Jennings during a standup outside Quba Palace, shortly after President Carter arrived

The day that Carter was to arrive, the streets of Cairo were decked out in Egyptian and American flags and there were posters of the two heads of state at the city’s major intersections. Faris, the hotel owner, suggested that I head to Quba Palace, one of the presidential residences, to get a good shot of Jimmy Carter. However, on my way to the palace, I met an Egyptian student who convinced me to head to the airport with him instead claiming that, as an American, I would have a vantage point to watch Carter’s landing, Of course, his theory did not pan out and I was just one among a sea of flag waving enthusiasts waiting to greet the U.S. president. When I realized my mistake, I grabbed a taxi to the palace, but it was already too late. I had missed my opportunity to see Carter, but, as I walked around outside the palace walls in a daze, people came up to me to grab my hand, thank me, and tell me how much they loved America. The whole experience was surreal.

If you don’t succeed at first try and try again. After two attempts to photograph Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat in an open limousine, I asked a police officer if I could go inside the cordoned off area, and, when he obliged, I took what I consider to be my first newsworthy picture.

I was still determined to take a picture of Carter, whatever it took. When I heard that two presidents were going to address the Egyptian parliament, I headed to Tahrir Square early and secured my position right on the curb. Unfortunately, I was in for another disappointment. When the convoy passed with Sadat and Carter standing in an open limousine, the crowd surged forward and all I could capture was people waving. Nevertheless, I still had one opportunity to get my shot when the two presidents were to leave the parliament building. This time, I was going to do whatever it took to get that picture, so I went up to a police officer and explained that I was an American and that I wanted to photograph “my president” with Sadat when they drove by. Without asking for further clarification or proof of ID, the officer gave orders to his subordinate who took me inside the police barricades to a spot in the middle of the square. When the convoy finally passed, I took one photo with my Olympus 35RD using a fixed 43mm lens, which I consider to be the first newsworthy picture I ever took.

By capturing this historical moment, I had sealed my fate. Although my visit to Egypt had been coincidental, I was bound to come back to finish what I had started. On a personal level, I had been smitten by the country and wanted a more immersive and extended experience. A few days after Carter left Egypt I flew back to Athens and resumed planning my trip to Crete which I had abandoned a little over a month earlier.

Thank you for sharing. We were in Cairo at this same time. Trip down memory lane!