Photographs and text By Norbert Schiller

In the next phase of the Tanker War, a US warship hit an Iranian landmine leading Washington to engage Tehran in what would become America’s largest naval confrontation since WWII. On the frontlines, the land battles between Iran and Iraq intensified with Baghdad scoring some strategically significant victories. In the middle of these sea and land confrontations, the United States fired a guided missile cruiser at an Iranian passenger plane, allegedly by mistake, killing all 290 civilians on board. This tragedy ironically paved the way to a negotiated settlement of the Iran-Iraq War as the incident made America Iran’s number one public enemy allowing Tehran to discretely come to a ceasefire agreement with Baghdad ending the eight-year conflict.

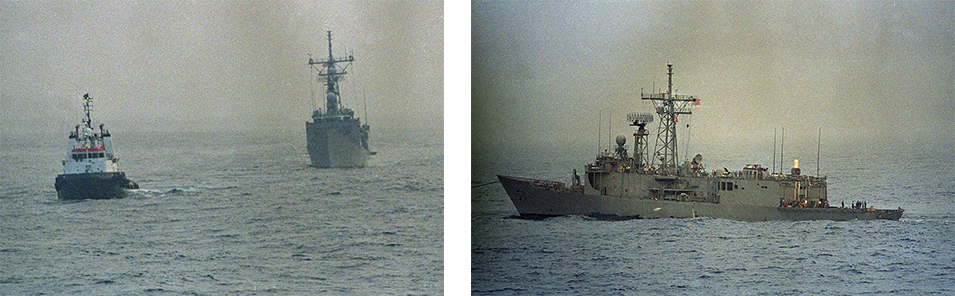

A Kuwaiti tugboat tows the crippled frigate, USS Samuel B. Roberts to Dubai for repairs one day after it struck an Iranian mine.

On April 14, 1988 the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts struck a sea mine that blew a five-meter hole in its hull causing severe damage and injuring 10 sailors. This was the second serious incident involving a US warship after the accidental attack on the USS Stark. The following day, we went up in the chopper to see if we could find the frigate, which was being towed to Dubai for repairs. The weather could not have been worse as a layer of thick haze prevented us from seeing anything located more than a kilometer away. Regardless, we were able to find the ship and come in close enough to take good pictures.

When it was determined that it was an Iranian mine that was responsible for damaging the US warship, the Americans retaliated with vengeance. Four days after the incident, the U.S. mounted the largest naval operation since WWII, appropriately naming it “Operation Praying Mantis.” During the course of one day, US forces destroyed two oil platforms that had been used by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards to stage attacks on shipping, sank one Iranian frigate, damaged another killing an undetermined number of sailors, and sank a number of Boghammar speedboats. The Americans suffered two casualties when a Sea Cobra helicopter gunship crashed into the sea during a nighttime operation.

Iranian firefighting tugboats extinguish the fire on the Sirri oil platform after it was bombed by American warships.

An abandoned Iranian machinegun sits on the Sirri oil platform

That day I was fortunate to be in a long-range helicopter equipped with an additional fuel tank. The distance we covered was the greatest that I had ever flown in a helicopter. When we got to the Sirri platform, the second of the two which had been attacked, Iranian fire-fighting tugboats were already on the scene trying to extinguish the blaze. It turned out that before the Americans attacked Sirri, they had sent a message ordering all crew to abandon the platform. However, instead of obeying the orders, the Iranian defiantly opened fired on the U.S. warships with anti-aircraft guns. In a matter of minutes, the gunfight was over and the platform was engulfed in flames.

After filming at the site, we flew on to Sassan oil field which was still smoldering from the American bombardment. In retaliation, the Iranians turned to their trusted Boghammars speedboats attacking a British-registered oil tanker, and while we were flying overhead, they fired a few rounds at our helicopter before shooting rocket-propelled grenades at an oilrig owned by the United Arab Emirates setting it on fire. That same day also marked a major turning point in the ground war. While the Americans engaged the Iranians at sea, the Iraqi army took back the strategic Faw Peninsula at the mouth of the Shatt al Arab waterway, which they had lost to the Iranians two years before.

Dead sheep thrown off of ships carrying livestock were often mistaken for Iranian sea mines.

Besides the Iranian attacks, the next big threat to shipping in the Gulf was the sea mines. The problem was not so much with the floating mines, most of which had been detected and defused, but it was those that remained at the bottom of the sea. The Iranians used a Russian-style mine from the early 1900s which is attached to an anchor made of salt. Once the salt dissolved, the mine would float to the surface becoming a hazard to shipping. In theory, the strategy was sound but in practice it was not that effective as the mines often got stuck at the bottom of the sea and surfaced months, years, and sometimes decades later. The French navy had had a great deal of experience with these mines because they had been sown extensively in the North Sea and off the French coast during the two world wars.

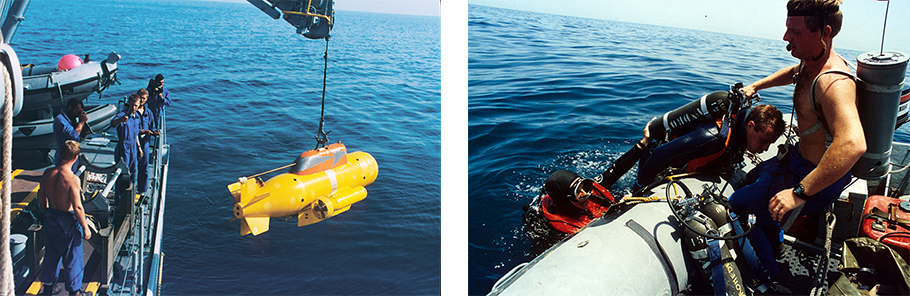

In the middle of May, I flew out to cover four French navy ships involved in a sophisticated mine hunting operation. They were going over areas that US and Belgium minesweepers had already combed for unsurfaced devices. I was aboard the Andromede when the crew found and detonated three mines over three days. The process, which was quite efficient, consisted of sending down an unmanned submarine to film the sea floor in search of mines. Once one was detected, two divers would go down and set a charge next to it. When the team was safely back on deck, the charge would be detonated and, as a result, a mixture of sand and sea life would rise to the surface of the water. After one such explosion, the ship’s cook was able to grab a large fish to turn it into a sumptuous meal for the crew.

The PAP (Possions Auto Propels) is being recovered from the sea and put on the deck of the Andromeda after it detected a mine stuck to the sea floor. Two French navy drivers are climbing back on the Zodiac after setting a charge next to the mine.

Bodies of Iranian soldiers are left partially buried in a pit while Iraqi soldiers on a boat celebrate recapturing the oil rich Majnoon Island.

After losing the Faw Peninsula, Iran shifted its efforts on the land war to prevent any more Iraqi gains. However, by the end of June, Saddam Hussein’s forces had scored another big victory recapturing the oil rich Majnoon Island. For most of that month, I was either with the National Liberation Army (NLA), an anti-Khomeini Iranian rebel force fighting alongside the Iraqi army or with the Iraqi forces on the frontlines. The aftermath of the Majnoon Island battle was a gut wrenching assignment, even for the most hardened war correspondents. Many compared the trench warfare in this conflict to WWI’s Battle of the Somme where soldiers’ rotting corpses littered the French countryside. What stunned me was not so much the carnage, but how the Iraqis treated dead Iranian soldiers. Like garbage, their remains were bulldozed into piles and dumped into huge pits with no one bothering to remove their tags so that they would be accounted for and their families notified.

When I finally returned to Dubai I felt that I deserved at least one day off from the news, so I decided to drive with AFP correspondent Alain Navarro to Abu Dhabi, the capital of the U.A.E, and enjoy a day at the beach. After a restful day, which included a lobster and champagne lunch, we headed back to Dubai, about an hour and half away. As we drove into the city we noticed men handing out newspapers at each major intersection. At first I didn’t think much of it, but when I noticed that it was the local paper Gulf News, which only came out in the morning, I stopped to investigate. To my utter dismay the headline in bold letters read: 290 DIE AS IRAN AIR CRASHES INTO SEA

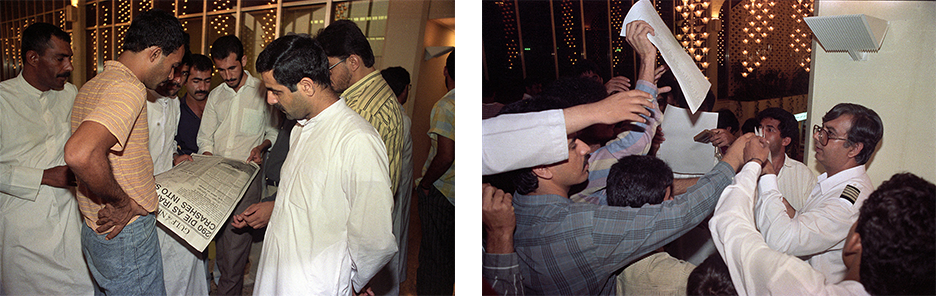

People waiting to fid out whether relatives or friends were on Iran Air 655 read a special edition of the local newspaper Gulf News. An employee of Iran Air hands out a copy of the passenger manifest.

Iran Air flight 655 was on a routine trip from Bandar Abbas in southern Iran to Dubai when the U.S. guided missile cruiser USS Vincennes blew it out of the sky allegedly after mistaking it for an F14 fighter jet. All 290 passengers and crew aboard were killed.

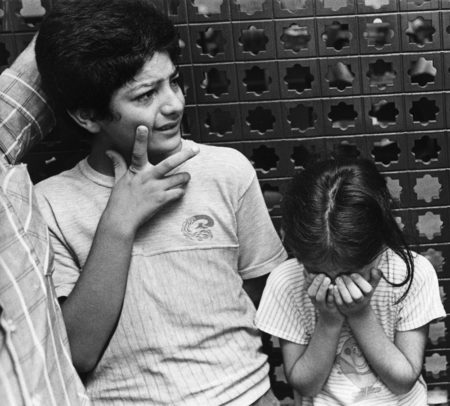

Iranian siblings cry as they await news of their parents who were supposed to be on Iran Air flight 655.

I instantly felt that cold sweat that sets in when one misses out on a big story. What was I going to tell my editors when they realized that the photographers from all the rival news agencies had managed to take photos of the wreckage while I did not? Alain suggested we drive directly to Dubai airport to see what was happening there. In the arrivals hall, he went around interviewing family members who were waiting for news while I ran around taking photos of the chaotic scene. Later, I raced back to my apartment to file the pictures while feeling terrible believing that I had missed the story.

When I called the photo desk in Paris to confirm whether they had received the pictures I had just filed, I apologized to the editor. However, the editor was somewhat perplexed and questioned, “Why are you apologizing?” I tried to make up an excuse about why I was unable to get up in a helicopter, but the editor did not seem alarmed as he had not seen any pictures of the crash scene from any other agency. I took that to mean that the other photographers hadn’t filed their photos yet.

To my surprise and great relief, I learned the next morning that the photographers who had gone up in helicopters had been unable to take shots of the crash scene because the Iranian navy kept all the helicopters away. The only photos datelined Dubai were the five I had filed the night before.

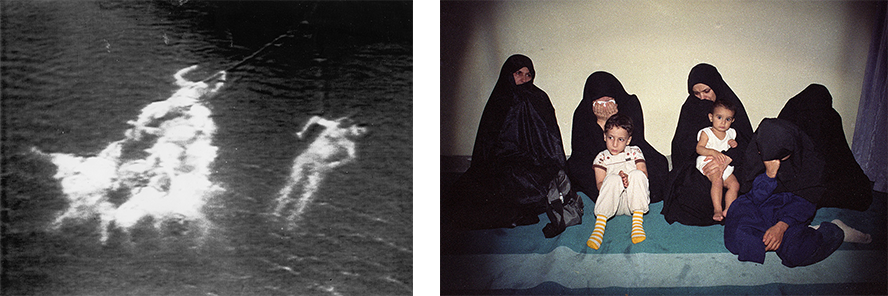

Bodies of passengers on Iran Air 655 can be seen floating to the water surface. Relatives of the dead at a memorial in Dubai the day after the Iran Air jet was shot down by the a US warship. Phot. (L) Iran State Television

After covering the memorial services in Dubai the foreign press chartered two service tugboats to go to Bandar Abbas, the closest Iranian port to the crash site, hoping we could cover the recovery effort. We boarded the two boats at night and the next morning, we were stopped by the Iranian navy as we entered Iranian territorial waters. When they realized that we were journalists, they let us proceed to Bandar Abbas.

An Iranian warship stops us as we approach the Iranian port city of Bandar Abbas. When they found out we were journalists they allowed us to proceed.

By the time we reached the port, the recovery had largely been completed and the focus was on the funerals the next day in Tehran. The Iranian authorities scrambled to get us all on flights to the capital, but only managed to get part of the group on a scheduled commercial flight. The rest of us were stuck waiting for hours for another flight that never materialized. Since it was getting late, the only option for the dozen or so journalists left behind was to board the C130 transport plane that was carrying the bodies of 72 of the victims for the funeral. When we boarded, we were struck by the suffocating smell of formaldehyde, the chemical used to preserve bodies. There was hardly any room in the cargo hold because the makeshift wooden coffins were stacked up to the roof and covered the entire floor from front to rear. A clear plastic tarp covered the coffins and straps were tied in place to hold them together. There was a folding canvas bench running the length of the fuselage on either side of the plane that served as seating.

When the doors were closed and the pilot started the engines, the combination of the deafening noise and the shuddering of the plane as the engine revved up in preparation for take-off, created a feeling of extreme claustrophobia only perpetrated by the fact that we were in such close proximity of the caskets. But what was to come next was even more hair raising. As the plane barreled down the runway and started lifting its front wheel, the straps holding the coffins snapped sending us into a panic and we began screaming and pressing ourselves against the caskets to prevent them from tipping over. When the pilot realized that something was wrong he immediately aborted the takeoff and came to a screeching halt at the end of the runway. One of the crew opened the cockpit door yelling, “don’t worry, nobody’s going to hurt you, they’re all dead.” Needless to say, nobody thought the joke was funny. In the end, we managed to catch an early morning flight the following day.

Thousands of Iranians take to the streets of Tehran carrying coffins of 72 of the dead to condemn America’s attack on Iran Air 655. All 290 passengers and crew perished when the USS Vincennes shot down the plane allegedly by mistake.

A few hours after we arrived in Tehran, I was sitting atop a flatbed truck photographing the 72 coffins which had broken loose the night before. The heat was stifling as the mourners carried the coffins through the streets chanting anti-American slogans. As soon as the ceremony was finished, I raced to the airport because I didn’t have my darkroom or transmitting equipment, and managed to get on a plane back to Dubai to develop and file my photographs the same day.

Families gather around the coffins of 72 of the victims during a memorial service in Tehran attended by thousands.

The eight-year war had taken a heavy toll on both Iran and Iraq in term of human and economic losses, and the idea of both sides agreeing to a United Nations truce with no victor seemed demoralizing. Since April, the Iranians had been losing the ground war but Ayatollah Khomeini had vowed never to give up until his archenemy Saddam Hussein was overthrown. However, the downing of the Iran Air flight ironically gave Khamenei an honorable exit from the war. By turning public opinion against America as the aggressor instead of Iraq, Khomeini was able to come to the negotiating table in a position of power. For Iraq, liberating the Faw Peninsula and Majnoon Island was enough to claim a victory. When both sides finally agreed to a U.N.-sponsored truce, they did so knowing they were able to sell it as a victory to both their constituencies.

On the second day of the ceasefire between Iran and Iraq, American officers aboard a US-reflagged oil tanker wave to photographers from the bridge of their ship.

When the ceasefire went into effect on August 20, 1988, I was up in a helicopter doing what I had done for the past 10 months. I knew my time covering the Tanker War was coming to an end and it was hard not to feel nostalgic knowing that this could be my very last flight over the Gulf. As I sat there looking out over the water from the helicopter reminiscing about the last year, I realized that I had finally earned that coveted rite of passage of covering a war. Not only had I covered the Tanker War, but also the end of the ground war. Now I was in a position to tell my own war stories.